In the last days of the Obama era, could the federal government finally recognize the Duwamish people and grant them the rights and benefits they’ve fought for ever since white settlers came to Seattle? Duwamish Tribal Chair Cecile Hansen isn’t holding her breath.

“I’m trying to have a good day,” she says. “I can sit here and cry, but I ain’t got time to cry.”

Hansen has been fighting for federal recognition for her people since she became tribal chair in 1975. So far, the tribe has seen no lasting success.

But there is precedent for a sudden reversal. For a brief moment in 2001 at the tail end of the Clinton Administration, the Duwamish were recognized, only to have the hard-won recognition swiftly snatched away when Bush came to power.

The only chance now for a last-minute reversal of the federal government’s long-standing refusal to recognize the Duwamish would have to come at a high level, says Bart Freedman, an attorney with K&L Gates, a law firm which works for the tribe pro bono. And while there are similarities to the situation in 2001 and now—a two-term Democratic president leaving office and a Republican president-elect preparing to take power—Freedman says this is unlikely.

If the unforeseeable happened, and the Obama administration declared the Duwamish a federally recognized tribe, it would be a quick end to the long, tortuous process Hansen and the tribe have gone through for recognition: petitioning government officials in both Washington state and D.C., compiling historical evidence, testifying before Congress, and much more.

But in the absence of action from Obama or Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, the tribe’s hopes lie with their legal appeal to a final decision from the Kevin K. Washburn, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs (who also oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs BIA). This decision was an attempt to put an end to the Duwamish quest for recognition once and for all. But according to Freedman, the decision is far from final because it relies on outdated 1994 criteria for federal recognition, rather than the newer 2015 guidelines. As Freedman told Real Change News, the BIA adopted those new rules in the same week it denied the Duwamish recognition based on the old rules. (The Bush Administration BIA pulled this exact same trick in 2001, he explained to Real Change).

“I’m hoping for a positive appeal,” Hansen says. “I’m really anxious to know what’s gonna happen because we’ve got a new administration coming on.”

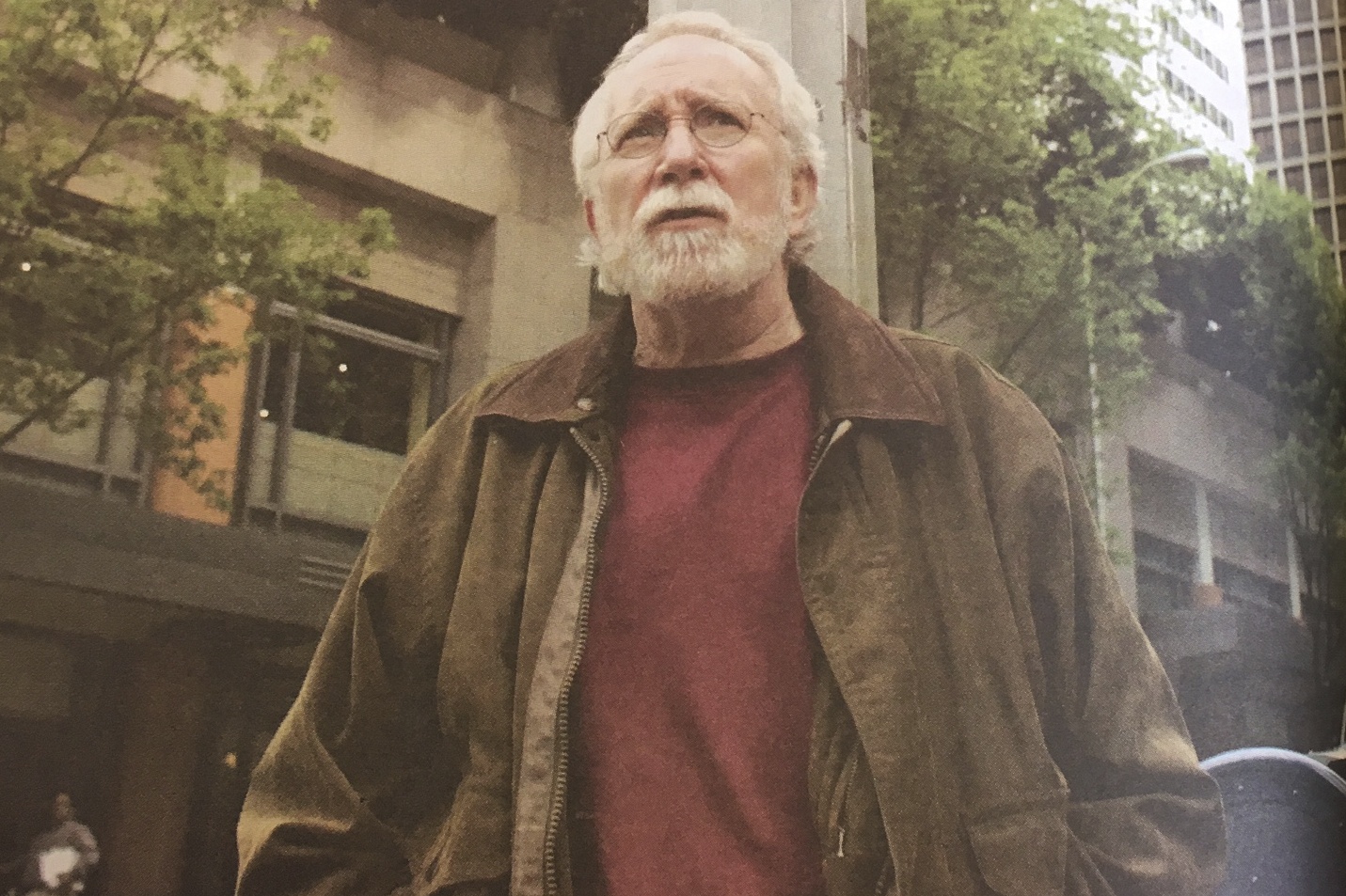

Hansen is the great, great grand niece of Chief Seattle, the Duwamish and Suquamish leader who welcomed and helped early settlers in the area (and gave this city a bastardized version of his name).

In 1855, Chief Seattle signed the Point Elliott treaty giving up 54,000 acres of land, including present-day Seattle, Renton, Bellevue, Mercer Island and other parts of King County, in exchange for hunting and fishing rights and other compensation.

But in the coming decades these rights would only be available to federally recognized tribes, and the federal government has consistently refused to recognize the Duwamish (and others, including the Chinook in southwestern Washington). As Duwamish tribal council member James Rasmussen told HistoryLink.org, the Duwamish don’t enjoy treaty rights to fish in their namesake Duwamish River, despite it sustaining them for generations.

Nowadays, in addition to the hunting and fishing rights, federal recognition would allow the tribe to receive grants to help with tribal government, health care, housing, education and more.

Hansen’s activism began in the 70s during the Fish Wars, when many Indians, including her brother, were fined and arrested for excersing their tribal fishing rights in Washington state. In 1977, two years after she was elected as tribal chair, the tribe filed its first appeal to the federal government for recognition.

The Duwamish got their first response from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1996, almost 20 years later, denying them federal recognition. The BIA claimed the tribe didn’t fulfill three of the seven requirements for recognition.

However, when the Clinton administration granted the Duwamish recognition in 2001, it was based on the assessment that they’d fulfilled all the necessary criteria for the administrative process with the BIA.

And the Bush administration’s basis for overturning federal recognition then was partly technical in nature. BIA secretary Michael Anderson, who was strongly supportive of the tribe’s efforts, forgot to sign a document, then signed it illegally on the new administration’s first day. After denying them recognition, the Bush administration BIA declared the Duwamish tribe extinct.

To Hansen, the federal government’s neglect to recognize the Duwamish is wrong on a basic label. “This is ridiculous. We sign the treaty, give up 54,000 acres, and we’re not recognized by the federal government?” she says. “I don’t know what’s it to them anyway, because I think every indigenous tribe in the United States should be acknowledged….Why does anybody have to prove it? We have all kinds of foreigners coming into our country and we don’t stop them at the gate and say, ‘Well, can you prove who you are?’”

The 2015 rejection from the BIA, and the tribe’s appeal, come after Washington’s 7th District Representative Jim McDermott reintroduced a bill in Congress to recognize the Duwamish — something he’d tried in 2003 to no avail. An act of congress is one of three ways a tribe can achieve recognition, in addition to an administrative process (which the tribe tried and failed to achieve so many times) or a lawsuit (which the tribe doesn’t have the money for).

The appeal has been complicated by efforts from other tribes who don’t want the Duwamish to be recognized. The Muckleshoot and Tulalip submitted a briefing saying the 2015 decision should stand. Hansen believes these tribes are afraid there will be competition for federal dollars, and that the Duwamish will build a casino (something she says they never wanted and have no plans to do).

Hansen isn’t holding out hope that the Obama will recognize the tribe in its last hours, as the Clinton administration did.

“He’s kind of busy, isn’t he?…They’re not thinking about this tribe sitting over in the city of Seattle,” she says of the federal government. “They’re not. They have such total lack of respect for this chief who gave up so much, and the people who are still wanting justice.”

But Freedman believes the lack of recognition from Obama can’t be blamed on his administration alone.

“I don’t think it’s a decision that’s specifically related to a particular administration,” he says. “Certainly it’s been clear that as the department tried to create new recognition regulations, those were the subject of intense lobbying by many parties, both tribal and non-tribal parties….I think it’s fair to say that the regulations that the Obama administration started out with, those draft regulations were a lot friendlier to the recognition of additional tribes than the regulations that were eventually adopted.”

The prospect of a Trump presidency looks grim for the Duwamish and its quest for recognition, Hansen thinks.

“Do you think that any indigenous people in the United States are gonna get any help from the new administration?” she says. “I doubt it. He lives in a tower, you know what I mean? He has never looked down and seen what’s beneath him. He doesn’t get it. And it’s scary.”

For now, Hansen is taking things one day at a time.

“Sometimes people can’t comprehend the tragedy of the Duwamish tribe of Seattle,” she says. “It’s easy for me, but sometimes people don’t understand.”

crobinson@seattleweekly.com