With the reality of Donald Trump as president, we can probably all agree that there are much more important things at stake than marijuana. Still, Trump’s decision to appoint U.S. Sen. Jeff Sessions as Attorney General has some in the industry freaking out at the possibility of a federal crackdown on the fledgling industry.

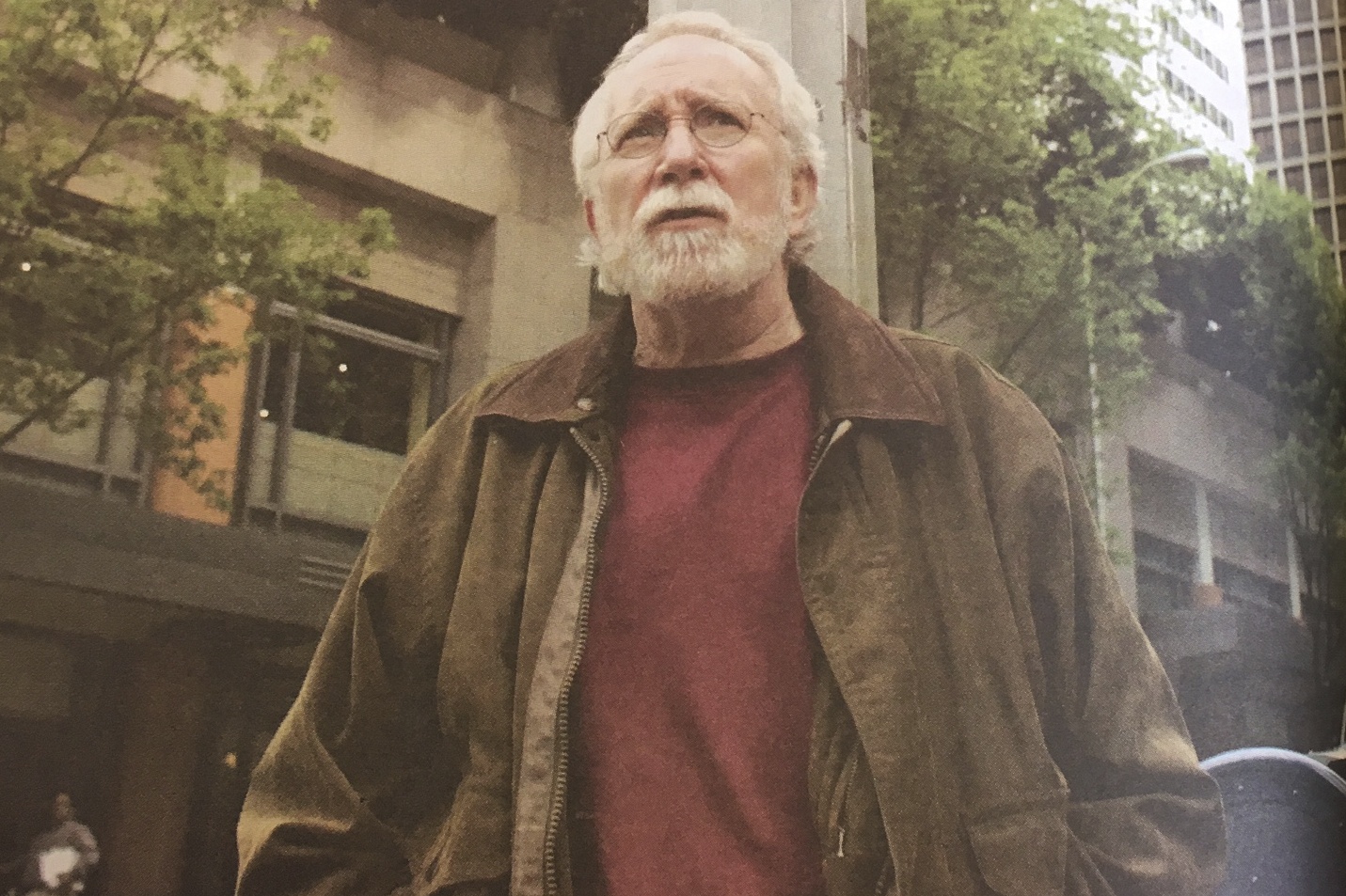

But if so, it’s possible that local law enforcement will defy the federal government if a new administration decides to take a hard line approach toward marijuana. This is according to Norm Stamper, who served as Seattle Police Chief between 1994 and 2000 and has since become a leading critic on the War on Drugs. Stamper speculates that local law enforcement might take this approach, which he compares to Seattle’s decision to remain a sanctuary city for undocumented immigrants in the wake of a Trump presidency.

“I think what you’re seeing right now is local police forces saying, among other things, we are simply not gonna become border patrol agents, we’re not gonna become ICE agents, we are municipal law enforcement,” Stamper says. “And whether one factors in sanctuary city status or not, you have a lot of police administrators saying that’s not an effective and smart use of local police forces.”

While marijuana is still illegal in the eyes of the feds — classified as a supposedly risky and medically useless Schedule I drug — an uneasy balance has been struck between Obama’s Department of Justice and states that have chosen to legalize the drug to varying degrees. Currently eight states have fully legalized marijuana, four of them joining the fold for the first time this election. A total of 29 states have a medical marijuana program.

There’s good reason to worry that the federal government’s leniency won’t hold come January, though a lot is still uncertain. Under a Trump presidency, Attorney General Sessions would hold an extraordinarily powerful position as overseer of the FBI, DEA and head of the whole Department of Justice, which enforces federal marijuana law and oversees federal prosecutors (in addition to enforcing just about every other aspect of US law).

Aside from the fact that Sessions has a long history of racism (a Republican-controlled Senate deemed him too racist to be a district court judge in 1986, and refused to swear him in) and a scary record on civil rights (opposing voting rights, supporting mass deportation and Trump’s probably unconstitutional proposed Muslim ban), he also really, really doesn’t like marijuana. Sessions seems to be a true believer in the discredited idea that weed is dangerous. “We need grown-ups in Washington to say marijuana is not the kind of thing that ought to be legalized, it ought not to be minimized, that it is in fact a very real danger,” Sessions said at a Senate hearing in April. It needs to be clear from the government, he thinks, that “good people don’t smoke marijuana.”

The fear is that Attorney General Sessions would have the power to severely cripple the cannabis industry.

“This is a guy who sounds like he’s speaking to us from the 1950s,” says Stamper.

“I think it’s entirely possible that Sessions would say, ‘No longer are we gonna take a hands-off position,’” Stamper continues. “Based on noises he has made in the past, I think it’s likely that he would do that. But I also think that there is enough grassroots support, there’s enough local experience, certainly in the states that have legalized, that would allow local governments to essentially exercise their own prerogatives on resources, on priorities.”

So it might be that liberal cities like Seattle decline to use their resources on cracking down on marijuana. This might even be true for more conservative parts of the state, Stamper thinks. Left to their own devices, they still might not be on board with a hard-line approach.

“Investing police resources in marijuana enforcement means that you can’t invest them elsewhere. And so I think local jurisdictions for political, for financial, for practical reasons, are going to be resistant, if in fact the feds decide they want to do that.”

Whether this is what the feds decide might depend on president-elect Trump’s nebulous stance on drug legalization. His stated positions have ranged from thinking in the ‘90s that we should legalize all drugs, to concerns about legal weed in Colorado. But while campaigning he stuck mostly to the view that legal weed should be up to the states.

If Sessions decides to crack down on marijuana, it’s hard to say what that would look like, Stamper says. “Nothing has changed with respect to the federal government’s authority to shut down what a state has described as legitimate operations,” he points out. “I would expect some symbolic enforcement. They may want to send a message to, quote ‘more liberal’ areas like Seattle — well like Washington, like Colorado, Alaska and California and Oregon — and say you know, we’re gonna defy the will of the people in your state because it’s the will of the federal government, which has the legal clout to do so — we’re gonna come in and shut you down. So they could do that and they could try to make some examples of some grow operations, of some retail operations.”

But apart from this, Stamper says, “I could not imagine the federal government saying we’re gonna devote a significant portion of our drug enforcement resources to local cases, to marijuana possession cases.” For one thing, “the federal government is woefully inadequate to the task of enforcing marijuana laws at the local level.”

Stamper has a warning for those would try to bring back the War on Drugs.

“You can’t control illicit commerce. I think we’ve learned that lesson with marijuana.”

crobinson@seattleweekly.com