By 9 pm, the results were looking bad for I-732. The crowd at the Peddler Brewing Company in Ballard, gathered there on Election Night to celebrate Carbon Washington’s groundbreaking carbon tax measure, seemed distracted. Many were glued to the big projector as it showed Hillary Clinton’s chances to win the presidency gradually slip away. As members of the campaign stood in front of the screen to speak, and even as they announced the likelihood of a loss on their own initiative, the crowd’s mind was elsewhere. Some early results had looked hopeful for I-732, but by 9 all signs pointed toward defeat, and Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” started playing.

The Carbon Washington crowd had been rick-rolled.

In the end, Washington voters killed what would have been the nation’s first carbon tax, with 58 percent opposed against 41 in favor. Apart from King County and tiny San Juan County up north—which represents just under 8,000 voters—every county in Washington rejected I-732, which aimed to be a revenue-neutral carbon tax modeled off the one in Vancouver, British Columbia. But even in liberal King County, with all its Seattle voters, the measure squeaked by with just 52 percent in favor and 47 percent opposed.

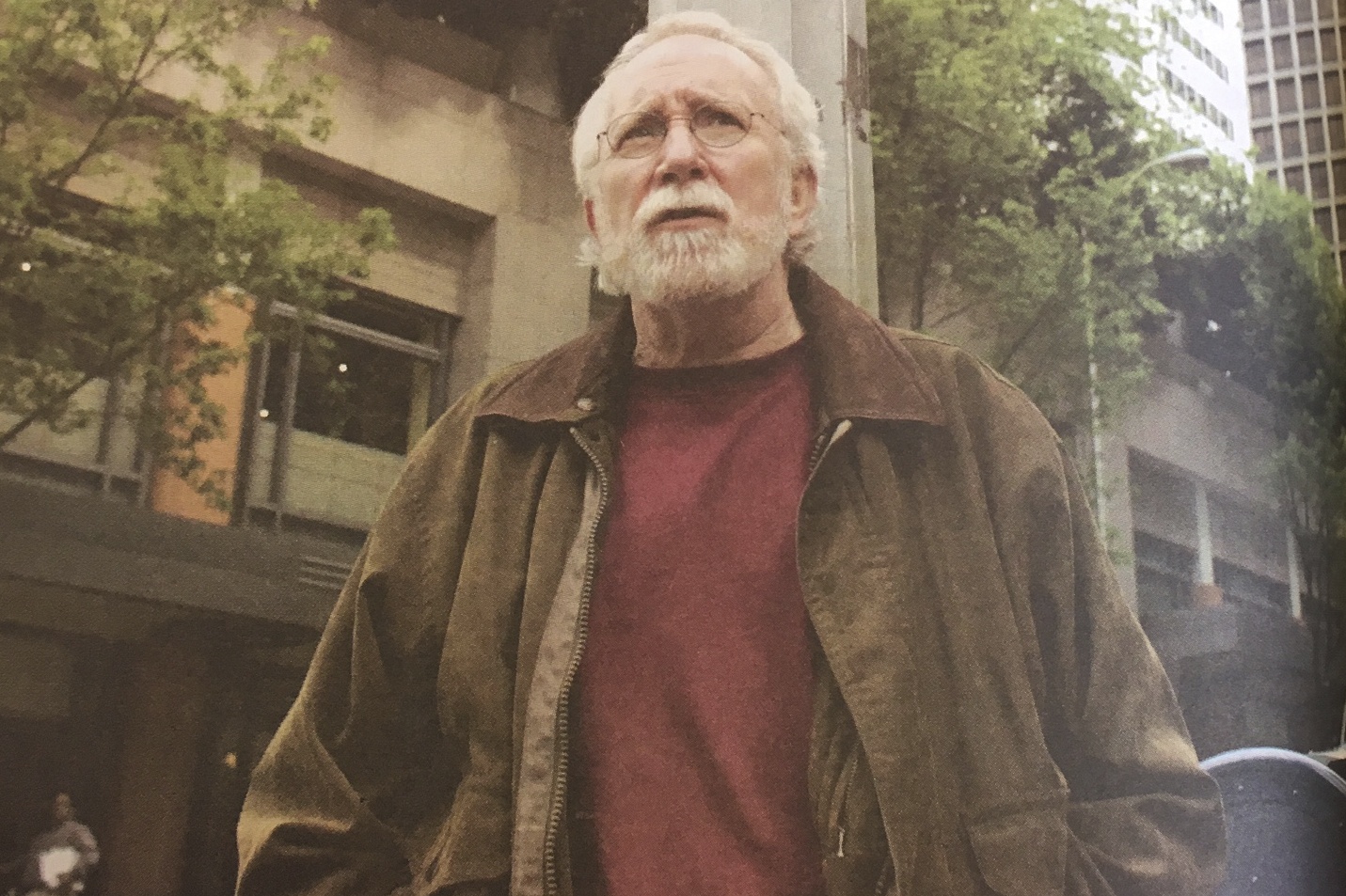

Not long after the results came in, Yoram Bauman, founder of the Carbon Washington campaign, retreated to a back room at the Peddler Brewing Company with members of the team. Later, he sat on a couch in the room behind his laptop, alone apart from campaign spokesperson Samara Villasenor.

“I think we’ve always been underdogs in this campaign,” Bauman acknowledged, looking sad. “I don’t think anybody thought that a carbon tax was going to be a slam dunk.”

It’s quite possible the campaign was doomed from the beginning. This is according to Ben Anderstone, political consultant with the firm Progressive Strategies Northwest.

“I don’t think it would have passed, looking at the statewide map,” Anderstone says. “Environmental measures, experimental measures are not easy to pass even if you’re in a fairly liberal state like Washington.”

Environmental measures tend not to do well with Republicans, Anderstone says, and it seems few moderate Republicans crossed over to vote for the measure. But even so, “the real killer was how badly it did with most Democrats.”

If it weren’t for the controversy and infighting among different environmental groups over the measure, Anderstone thinks it would probably have been more successful in Whatcom and Jefferson Counties (the latter containing liberal Port Townsend), which tend to approve such environmental measures. It still might have lost, but maybe by just a single digit margin.

“It could have merely been a left-right divide like environmental issues tend to be in Washington,” Anderstone says. But it wasn’t.

A late October poll of 502 registered voters found 28 percent undecided, against 40 percent in favor and 32 percent opposed. For undecided voters, Anderstone thinks, I-732 looked complicated, and the fact that it was controversial among environmental groups wasn’t lost on them either. When people are uncertain, Anderstone says, they tend to vote “no.”

Still, Anderstone points out that the campaign “didn’t fail miserably,” and so is “a good test balloon for how feasible this issue is.”

Jill Mangaliman, a member of the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy that opposed I-732, is unsure whether the opposition campaign can be credited with defeating I-732. “It’s possible,” they say. But, “there was pretty widespread opposition to it.” Mangaliman credits labor organizations and environmental activist Naomi Klein for their influential opposition to I-732.

Mangaliman believes the campaign failed fundamentally because it lacked a broader coalition, and that voters in marginalized communities saw that it wouldn’t benefit them.

The Alliance—which is made up of a number of social justice organizations, including Mangaliman’s environmental justice organization Got Green—opposed the Carbon Washington campaign for a few reasons, including what it believed was a failure to include low income people and people of color in the decision making process, and for the fact that it would have been revenue neutral. An acceptable solution, according to the opposition (articulated in an editorial by Mangaliman in The Stranger), would involve raising revenue and investing in green jobs and the communities that will be hit hardest by climate change.

“I think it is a moment for the environmental movement,” Mangaliman says. “There are two environmental movements—there’s one that is connected to the communities that are most impacted, and there’s one that wants to keep the status quo…. I think Washington voters took a huge step yesterday.”