The old adage goes “History is written by the victors.” And the United States? Baby, we’re the best at winning, in the truly Charlie Sheen sense of the word.

“History is written by the victors” rings true because what we consider history is always presented less as an unbiased chronicle of events than as a hyper-condensed, easily digestible narrative. From an early age, students in our country are taught a story of American triumphalism; one where we’re almost always the good guy. That kind of “Sure, slavery was bad, but we freed them eventually and then Civil Rights happened, so it’s basically equal” tone. It’s not that the country hasn’t achieved some spectacular things, it’s just not a very full picture.

Howard Zinn attempted to fill some of the blind spots that never get taught in class with his 1980 book, A People’s History of the United States. It highlights the plights of common people who consistently battled against the consolidation of elite ruling power and the unfair systems of repression it put in place. It too can be criticized for what it omits, but it certainly fleshes out areas standard textbooks ignore.

An engaging if controversial text calls for an engaging if somewhat controversial interpreter to present it for a new audience. Enter Mike Daisey and his new Seattle Repertory Theatre production, A People’s History. The famed monologist and former Seattleite has showcased his knack for storytelling on stages across the country and for outlets like This American Life (where he drew heat for an episode about Apple that included fabrications, which Daisey chalked up to theatrical dramatic license). The show’s run features a very unique setup: Daisey goes chronologically through the 18 chapters of Zinn’s book, one chapter per performance. Over the course of his stay in the Rep’s Leo K. Theatre, he’ll perform two full cycles of all chapters.

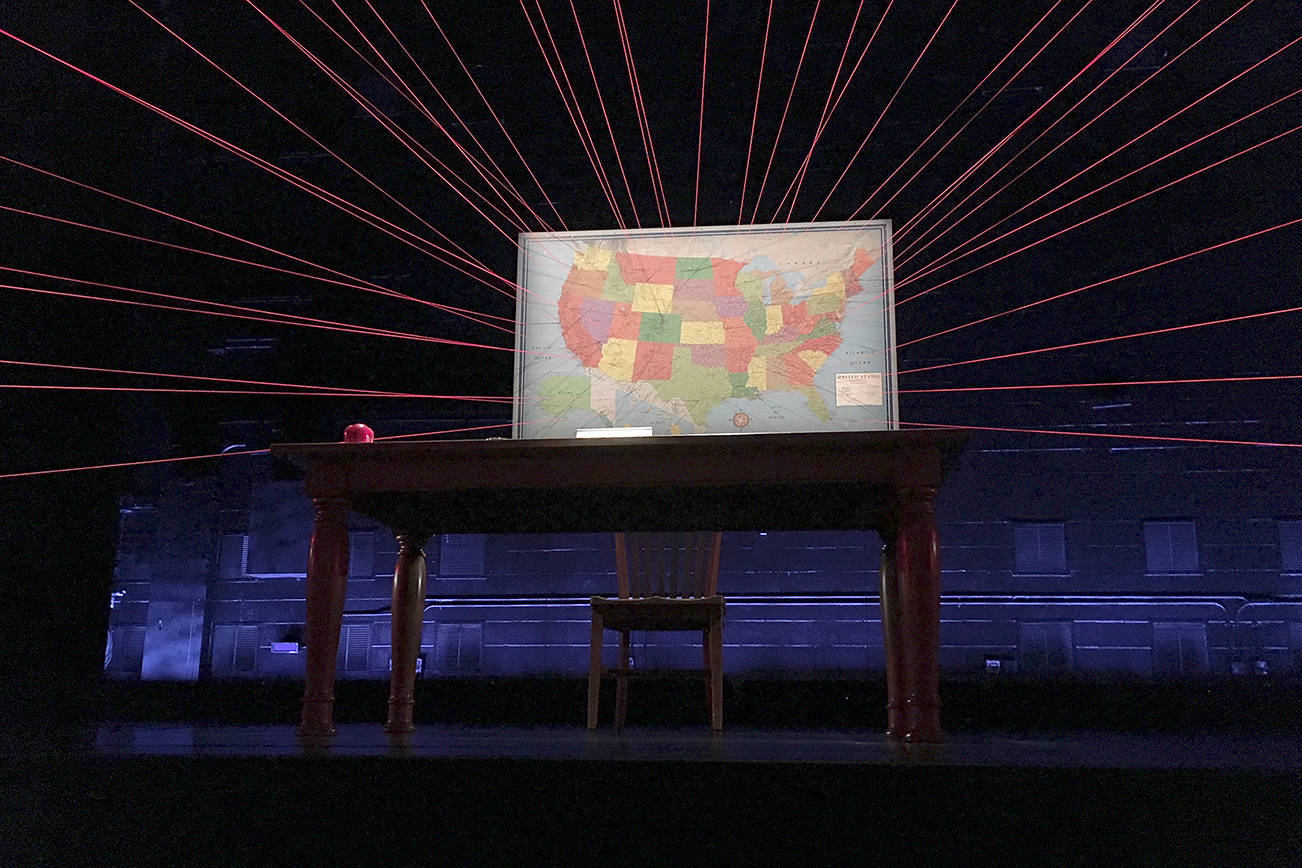

The setup is very simplistic, with Daisey positioning himself center stage as a teacher behind a desk with all the scholarly accoutrements: a name plate, an apple, scattered notes, and a map of the U.S. (in this case suspended by vividly jutting strings). Essentially, it’s a 90-minute drop-in night class with the most fiery history prof around (I even fell into my old habit of drawing on my knuckles while the teacher was talking near the end of the performance). Each night Daisey takes a direct passage from the given chapter, contrasts it with what is taught in history class, and ties the historical lessons to current happenings (occasionally referencing chapters — i.e., shows — that have come before or will come soon). In my case, that was Chapter 8, which covered the awful working conditions of the early 20th century, the context of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the concept of resistance, the rise and faults of unions, the Industrial Workers of the World (aka Wobblies), socialism, the Seattle General Strike, and even the controversy of Megyn Kelly’s racist blackface comments that had happened that day.

The passion with which Daisey attacks the topics makes the show an entertaining affair rather than a slog. He doesn’t mince words when talking about how standard U.S. history books are “shitty defective texts;” how we care about history only in terms of what it means in our individual lives; how history will mainly remember our times for being the people who “fucked the planet”; and his own racist collegiate ignorance as a 19-year-old white guy who grew up in Maine. Daisey takes a confrontational stance with his audience, knowing it’ll be predominately white people affluent enough to attend the theater, questioning where they’d actually have fallen during the class-warfare battles of the past. While he does a admirable job calling out his own straight white male culture, it wouldn’t be surprising if more woke audience members found certain ranting explanations to come off a bit like mansplaining. That said, even if you disagree with some of his points, it’s not going to shake his conviction. While it’s not exactly theatrical, Daisey’s combo of seriousness and comedic zest make A People’s History a fairly captivating lecture on what the history that wasn’t written by the victors means today.

After seeing A People’s History, we got Daisey on the phone to discuss the process of tackling U.S. history in this theatrical setting.

When approaching A People’s History, what led you to deciding to break Zinn’s text up into 18 separate shows, one for each chapter?

It was really clear to me that… [you’d] fundamentally have to make an abridgment if you decided to talk about this book in a single evening. And I wasn’t that interested in an abridgment. I wasn’t interested in the sort of traditional frame of when a theatrical work adapts a different form.. generally [it’s] an attempt to create a dramatic intensification of the thing itself while not actually covering the substantial material that’s in the other thing. And I knew that I wanted it to be not only be Zinn’s text, but then also grapple with the default history, which I personify mainly through my U.S. history textbook. So I knew I had all that material that I wanted to address, so I wanted to find a form that was large enough—a container—that you could legitimately feel like you covered a course in American history. It was sort of determined by the material I wanted to cover: the form matched the content.

Considering the show I saw had current events that occurred that day as part of the production, how much of any given performance is planned out versus adaptable to the daily happenings?

Well that’s a hard question to answer in a percentage, because the work is fundamentally extemporaneous in nature. Much as one can’t actually dissolve down a jazz performance into what was preparation and what was not, it’s pretty hard to say.

The classic question for any artwork is “how long did you prepare to make this artwork?” And all the monologues are built extemporaneously, so there’s a period I work on the show, but really it’s actually happening in front of you the moment you’re in the room. And then simultaneously, it actually took my entire life. I literally had to dedicate myself to being a monologuist and spend 20 years telling stories on stages over and over again. So all three of those things are simultaneously true.

Because of the history class format of the show, how do you decide when to reference chapters that people likely haven’t seen you perform while still making each show something that stands up on its own?

I practiced this before: I did a 29-night, 44-hour novel a couple of years ago (All the Faces of the Moon). So that was substantially more complicated, because there you had to make it engaging on any given night despite the fact that a lot of your immediate audience will not have been following the novel as its been going. And then what happened was each night’s performance was podcast immediately upon conclusion. So some people were following, but the majority were not. That was a lot harder narratively to connect.

American history has this beautiful thing: that we’re actually used to being taught in sections about as long as I’m talking. Because the last time people were in a classroom, they experienced American history in that way. So then it sort of exists in the context of a drop-in class.

So generally what I do is talk about references to immediate chapters that have proceeded to draw narrative lines. If I’m mentioning it, I’m probably doing it also to have an opportunity to recapitulate what the major thought was that was touched on in more depth earlier.

Are there plans to release recordings of A People’s History at some point?

I record all of them. I record everything I do. I think in the fullness of time as I perform them different places, one of the hopes is that, when I feel it’s the right place, I certainly plan to let it exist in a different form that more people can participate and join in with.

Do you have favorite chapters to perform?

So the show is not currently booked after Seattle. I’m in talks with people to do it, but I haven’t actually committed to doing it. And to be honest, one of the reasons I haven’t fully pulled the trigger is I wanted to make sure I could continue to do it. Because I have a lot of work I feel like I could be working on, and there’s always a real tension between the time spent making that and whatever you’re currently working on. And telling a 30-hour story of the entire history of America is very involved, and it take a tremendous amount of energy every single day. In addition to the energy of performing it, I spend about six hours a day working on that evening’s show.

So all that’s to say, the experience of performing this particular monologue versus other monologues I’ve done is fundamentally that it is painful. I find it very painful to relive all of American history. To talk in as intimate and as charged a way I can about its atrocities and excesses is painful. And so the dominant mode for me is feeling like I’m wrestling with this enormous history.

It also reminds me of sanding down a floor for refinishing. The work of the show is fundamentally trying to burn down the layers of American triumphalism to make the past look less glorious, and thereby have it have some relationship to our inglorious present. So because of the way that works, I don’t actually find myself luxuriating in any particular material, because any of the material that is terrifically charged — and there is a lot of it — is painful to present. It’s not actually that pleasurable to execute it expertly or to hurt your audience. It’s not something that someone wants, but feels called to do in the service of a story that you hope can scour away those layers to some degree, or at least open the possibility that we should be trying.

A People’s History

Thru Nov. 25 | Seattle Repertory Theatre | $50–$57 | seattlerep.org