Few events on the calendar of Seattle’s bustling improv comedy scene are bigger than this week’s Seattle Festival of Improv Theater (Feb. 20–24). Hosted by local comedy institution Jet City Improv (JCI), the fest—now in its 17th year—brings together 21 improv groups from Seattle, other U.S. metroplexes, and Canada to put on a dozen shows of made-up-on-the-spot hilarity. This year’s headlining group, L.A.’s Theme Park Improv, even features recognizable comedic faces including Big Bang Theory’s Simon Helberg.

One group not performing at SFIT? Empty Orchestra.

The reason? Essentially the artistic director blacklisted an improviser, tried to keep this info from her, made up reasons why she should be banned, and then when proved wrong wasn’t held publicly accountable. It’s emblematic of what many performers with JCI-ties perceive as a problematic culture fostered by the men running the theater.

As with other festivals like SFIT, many groups don’t end up making the cut. That wasn’t the case for Empty Orchestra, a JCI show in which audience members did karaoke, which then would inspire the improv scenes. After a sucessful original staging of the show in January 2018, JCI artistic director Chris Dewar arranged a meeting with Empty Orchestra director Graham Downing in late October 2018 with the goal of restaging the show for SFIT, but there was one catch—performer and assistant director Britney Barber couldn’t be a part of the production.

The request came as a surprise. Not only had Barber been a key component of Empty Orchestra, but she had been doing improv with JCI since 2013 performing as a member of the flagship JCI cast (though currently considered part of the theater’s part-time “emeritus” ensemble).

According to Downing, Dewar initially said the reasons Barber couldn’t be involved were confidential, but when pushed, Dewar cited Exit 192 Improv at the Historic Everett Theatre, an independent monthly improv show that Barber had founded in her hometown. She was no longer welcome at Jet City.

Downing left the meeting without agreeing to Dewar’s terms and reached out to inform Barber about what had happened. She was completely unaware she had been blacklisted, and felt surprised, taken aback, and hurt by the revelation. But more than anything, she was suspicious if the full story was being told.

It turns out this was only the tip of the iceberg for Barber’s conflict with JCI—one that underscores what many performers believe is due to the men on the JCI staff wielding unchecked power, leading to a culture where players are afraid to speak out in fear of retaliation.

Word travels fast in the tight-knit Seattle improv community—which includes main companies Jet City, Unexpected Productions, CSz Seattle (ComedySportz), and plenty of independent improv groups that perform at venues like the Pocket Theater. Shortly after Barber became aware of the situation, her wife, Dr. Jennifer Barber, called out Dewar in an extended Facebook post about Britney’s apparent ban (Britney is not on any social-media platforms). The information sparked questions about the situation that were directed at JCI’s ombudspersons.

At Jet City, two cast-elected ombudspersons act as player advocates and representatives to handle conflicts between players and the JCI staff or board, sometimes via anonymous reporting. When the news that Barber was no longer welcome at JCI began to circulate, ombudsperson Kris Corbitt began fielding questions from players looking for the rationale. Barber herself contacted Corbitt to get concrete reasons. To Corbitt’s knowledge, no cast player had ever been blacklisted, and only “extreme reasons” had led to others bannings: a theater volunteer caught stealing from the donation box or a third-party improviser caught shooting heroin in the bathroom. Whatever Barber’s alleged offense, it certainly did not seem to rise to those levels, and even then those offenders were told directly instead of being informed via third party, whereas Downing had to inform Barber.

Corbitt set up a call with Jet City staff—Dewar, JCI co-founder and associate artistic director Mike Christensen, managing director Keith Dahlgren, production director Brandon Jepson, education coordinator Kate Drummond, and marketing manager Maddy Noonan—on Nov. 7, 2018, and was given five reasons for Barber’s expulsion that constituted a “pattern” of objectionable behavior (which she shared with Barber via email later that day): 1) a show Barber pitched for the 2017–18 season called Minority Report was pulled in August 2017 before it was set to open in November 2017; 2) Exit 192 conflicted with Jet City putting on shows in Everett; 3) Jet City took offense to an email Barber sent detailing the production costs of Empty Orchestra; 4) Barber wouldn’t meet in person to discuss issues stemming from feedback she sent about the theater practices regarding Pitch Night; 5) a general negative attitude toward Jet City.

While these allegations surprised Barber, she felt confident in defending herself. She had a paper trail. “They were hoping that I didn’t have proof that they were lying about me, and hoped that they could get away with it using these invalid reasons,” says Barber.

Debunking Claims

For starters, Barber didn’t pull Minority Report. She had originally pitched the idea as a regular showcase show for local minority performers, but after it was picked up to be a one-off part of the season, it became problematic. Eventually it was removed from the lineup by Barber and the artistic director at the time, JCI co-founder Andrew McMasters.

On the second point: While JCI’s code of conduct asks for players to get approval from staff before starting regular independent shows, Barber had done so before launching Exit 192 in March 2018. In emails dated Jan. 18, 2018, Barber told Christensen of her plans to start the show in Everett, to which Christensen responded “no worries we’ll just work independently.” While the Historic Everett Theater (HET) did have a relationship putting on Jet City’s Twisted Flicks (a show in which improvisers mute the sound of a bad movie and make up their own dialogue, music, and sound effects), the theater had to cancel the working relationship because, according to HET Manager Curt Shriner, they “were losing money on every show.” After failing to get an approval from the Jet City board to do a house split (similar to Exit 192’s) with HET, Christensen pitched the idea of bringing an independent version of Twisted Flicks (i.e., not using the Jet City name) to HET, which could be read as a more direct violation of Jet City code than what Barber was accused of doing. “You’re trying to undermine your own theater and do what I’m doing, when I’m an independent free agent living in a different city,” says Barber. “You already have your own theater and now you’re trying to push me out of a theater in my hometown.”

In the Empty Orchestra budget email, Barber laid out $216 worth of items that she purchased out of pocket (such as glow sticks for the audience and a 100-foot HDMI cable), notes that they may be needed if Jet City wants to put on the show again with the same production values, and doesn’t ask to be compensated for the costs. There’s no indication that the staff took the email poorly, as Dewar’s reply email begins: “Thanks for sharing this info on the EO production cost and for helping to financially support this amazing show!”

Barber chalks up the “negative attitude” assertion to overblowing artistic differences, which leads to the key conflict point: the Pitch Night feedback email and communication issues around it. It seems to be the root cause of the issues between JCI and Barber, or, more accurately, Dewar and Barber.

In March 2018, Barber was told by JCI ensemble member Douglas Wilott that Dewar was seeking feedback regarding Pitch Night, a once-a-year event in which Jet City community members pitch ideas for long-form themed shows which populate JCI’s season calendar. After Dewar took over as artistic director in October 2017, the decision was made to start charging people $10 to attend and pitch ideas. It was not a popular decision. “I don’t know of a single player who didn’t question, ‘Why are we charging for Pitch Night?’ ” says Corbitt.

Forcing volunteers to pay troubled Barber, who sports a fiery native Philadelphia temperament. “Britney is a very passionate person who cares about the littlest person in an organization,” Corbitt says. “The people she cared very passionately about with Jet City were our volunteers.” Barber is the type who can expound on a single interview question for an hour straight if not interrupted (as she did during SW’s interview with her), and so her email was pointed.

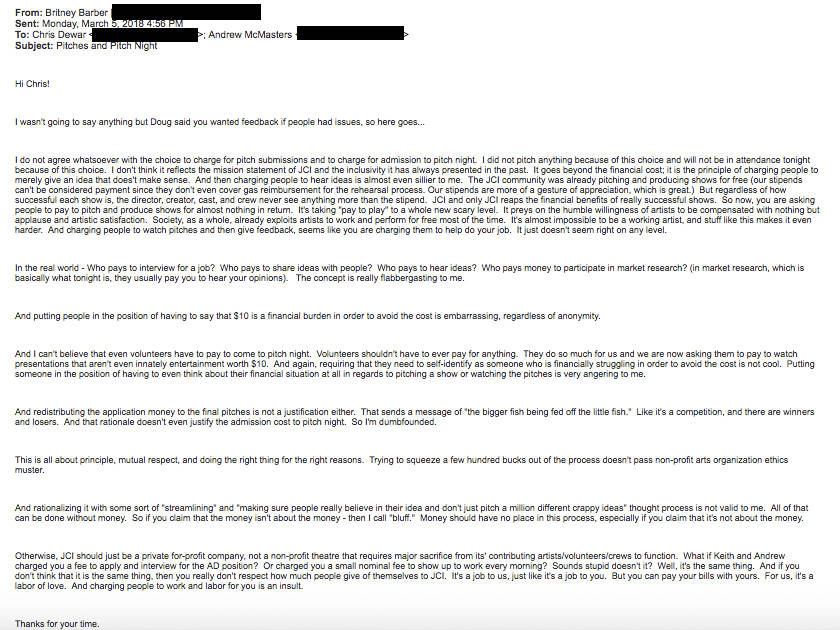

In the 755-word email to Dewar (which is posted in its entirety below), she states that “I don’t think [charging for Pitch Night] reflects the mission statement of JCI and the inclusivity it has always presented in the past. … It’s taking ‘pay to play’ to a whole new scary level. It preys on the humble willingness of artists to be compensated with nothing but applause and artistic satisfaction. … Society, as a whole, already exploits artists to work and perform for free most of the time. It’s almost impossible to be a working artist, and stuff like this makes it even harder. And charging people to watch pitches and then give feedback, seems like you are charging them to help do your job. … In the real world – Who pays to interview for a job?” At its most biting she writes, “What if Keith and Andrew charged you a fee to apply and interview for the AD position? … Sounds stupid doesn’t it?”

In response, Dewar replied, “Thanks for reaching out to me with your concerns regarding Pitch Night. I would be more than happy to discuss the changes to Pitch Night with you either in person or over the phone. Please let me know how you would like to proceed.” Barber replied to Dewar’s response saying she felt she was clear with her points and had nothing to follow up with, though if he wanted to continue the conversation they could do so via email. Dewar insisted that “Email is unfortunately not well suited for productive/constructive conversation and I encourage you to share your thoughts with me either voice to voice or face to face.” Barber again declined, citing her diagnosed anxiety and her own tendency to become emotional in face-to-face conversations regarding issues she feels passionately about. The email exchange reads as relatively mundane, but Dewar took it personally in a way not reflected in his level written responses.

“Chris received the email, and he was irate,” says Ethan Smith, who worked as Jet City Improv’s marketing and communications manager from February 2017 to May 2018, and was in the staff meeting immediately following Barber’s email being recieved. “You should know, we had that meeting before Pitch Night where multiple members of the staff actually said very similar things to what Britney [wrote], myself included. That we shouldn’t be charging volunteers. We have a volunteer who takes a two-hour ferry to get to the theater, and she had to pay $10 at the door. It’s insane. In the meeting that day, Chris said there have to be repercussions for people—he hated digital fighting; people arguing over email. He asserted that Britney had to speak with him in person, and that she was going to be suspended or banned.”

Despite the initial reaction in March, Barber wasn’t informed there was an issue until hearing about Downing’s SFIT meeting in October.

“When I read the email from Britney … I didn’t actually understand what he was so upset about and where he was getting that there was such a personal attack in it,” says Corbitt, who urged Dewar not to do anything that could be seen as retaliation. “My fear was that if there was some disciplinary action about this particular email that it would cause a lot bigger issue with players. If players don’t feel comfortable emailing feedback like this, then we’re going to have problems.”

Fear of Retribution

Fast forward to November 9: Two days after telling Corbitt the five reasons why Barber was no longer welcome, marketing manager Noonan sent an email to JCI ensemble performers stating the staff was aware of concerns raised about Barber’s status, that they were “taking the weekend to create a holistic and thoughtful response,” and that there would be an hour of open discussion about the topic after regular evening rehearsal on Nov. 12.

In the response email sent the following Monday, Noonan stated: “Firstly we want to make clear that Britney has not been ‘banned’ or ‘blacklisted’ by the company, and she is welcome at Jet City Improv at any time.” They defined her status as “pending,” and clarified that Dewar should’ve informed her of her “pending” status directly, while emphasizing that communications should be done face-to-face or at least by phone. Jet City did not include the five reasons for excluding Barber that they had presented to Corbitt. As stated in the email, “We want to have these conversations with Britney, and we want to have these conversations with all of you!”

However,Chris Dewar did not attend the post-rehearsal Q&A, which would, it was claimed, “give players a chance to ask questions and express feedback with JCI-cast-facing leadership present”; only Drummond was available to take questions, and Barber was not invited. The hour-long meeting ended up stretching on for two and a half.

Dewar’s absence spoke to a larger point about Jet City players’ fear of staff retribution. Jet City Improv is not a money-making venture for most performers. Ensemble performers get paid in the neighborhood of $15 for each performance of the flagship show, while long-form shows that require months of planning, weeks of rehearsal, and performances net only a $50–$100 stipend for the show’s entire run. (Empty Orchestra performers earned $90 total for a six-show run.) The one way Jet City players can make decent money is through teaching improv classes at the theater and performing in away shows—i.e., road shows that bring in more money. But because these spots are so limited and some performers rely on the limited checks to pay the bills, players fear that if they provide feedback the staff doesn’t like, they’ll be frozen out of those well-paying opportunities.

Smith said he pushed for two years for the company to administer anonymous surveys because performers felt it was really hard to talk to the staff. “I told Chris Dewar and Keith Dahlgren—to their faces—that they always assert, ‘We’re nice people. People just need to talk to us.’ … But I told them that they don’t understand that when you’re the artistic director and managing director of an over-$500,000 nonprofit organization, you stop becoming just people. [Because of] your positions of authority, people are afraid to speak to them out of fear of repercussions. Well, Britney tried to come to them, and look what happened.”

The only Jet City performer to take an immediate stand with Barber was Samantha Demboski. While not a member of the JCI ensemble, Demboski had been in Empty Orchestra with Barber and was cast in the then-upcoming Wes Anderson-themed long-form show, Yes Anderson. Despite feeling that it would probably end her chances of performing at Jet City, she dropped out of the Yes Anderson cast. She felt the roundabout way which Dewar tried to get Empty Orchestra to exclude Barber from SFIT, along with the Exit 192 conflict rationale, were blatant misuses of power.

“[Chris] very directly said he sees his job as defending the staff from other people,” says Demboski. “What they need is leadership that understands that it is the players and that community that is responsible for all of their creative content, and aren’t a resource to be utilized and then sort of discarded if they don’t say the right things. Their entire show-creation format for long-form things is that people bring their ideas to Jet City, end up being the ones to cast and execute them, and—in my opinion—don’t get the money back that they should.”

Issues With Women

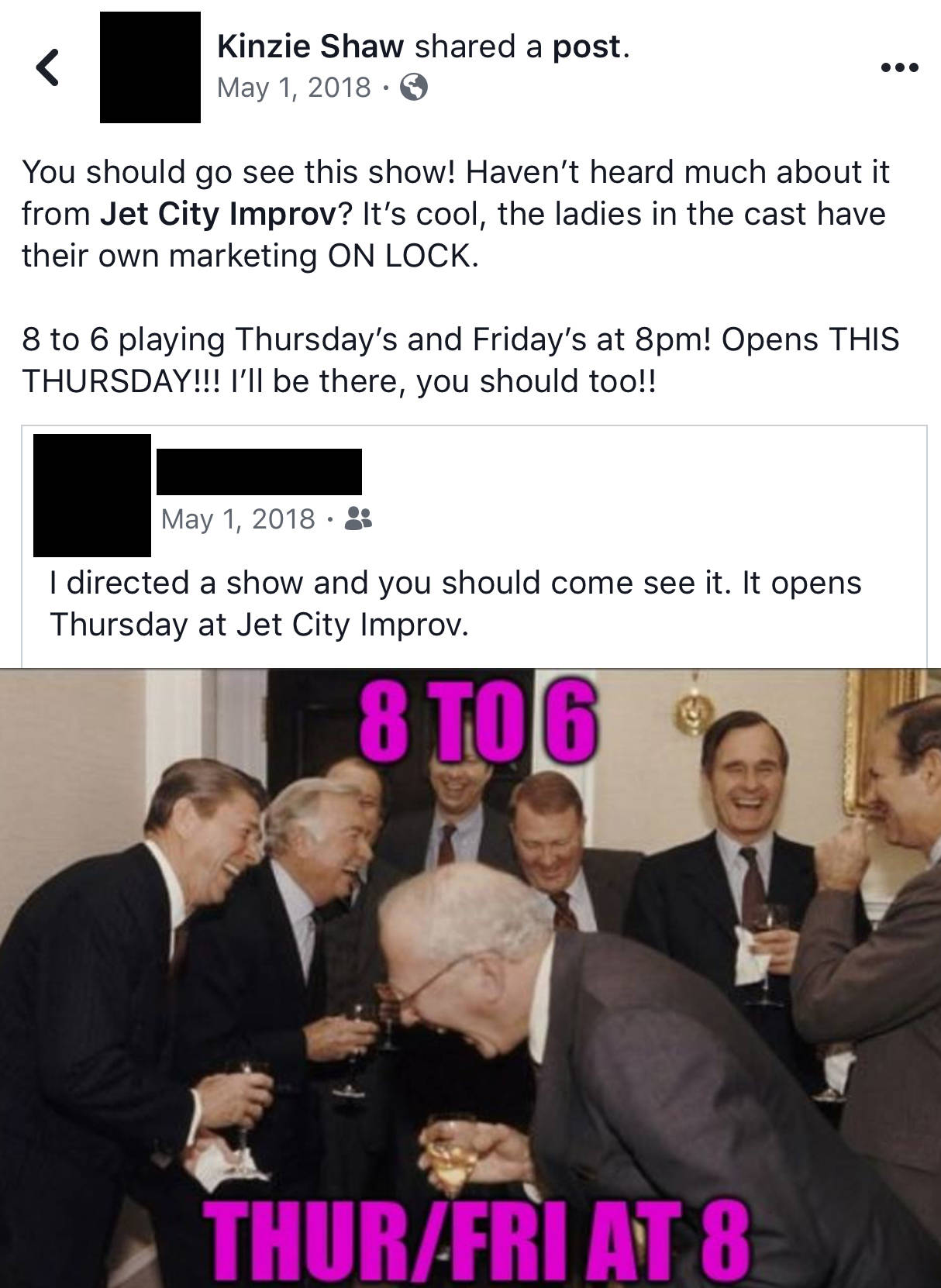

Barber isn’t the first female performer to have issues with Dewar. Kinzie Shaw—who, while not in the JCI cast, has improvised in past long-form shows at the theater—drew Dewar’s ire after he saw a Facebook post she made. Shaw’s wife co-created the feminist workplace long-form show 8 to 6, which ran in May 2018. Feeling the show had not been properly marketed by Jet City, Shaw took to Facebook to inform people that the show was indeed happening. After seeing the post (which can be seen below), Dewar called in Shaw’s wife for a meeting saying the post had hurt the staff’s feeling and that she needed to rein Kinzie in.

“[I felt] the tone of what I had posted, and the repercussions my wife had gone through, were not equivalent,” says Shaw. “I know what kind of men work in that office, and I know how they like to handle certain situations. There’s just a lot of misogynistic behavior that I experienced over the years. Just the environment in general feels like a very old boys’ club.”

As examples, Shaw cites how many of the shows pitched at Pitch Night were “very misogynistic and gross,” and that when she performed as part of Twisted Flicks, Mike Christensen “wouldn’t assign any male characters to female players. He just didn’t think females could do justice to the male characters, cause they were mainly leads. So he needed the ladies to play the ladies, even though men could play both men and women.”

Smith also noted the men on the staff are openly sexist behind closed doors, bandying about lines like “You know how female performers are” when reviewing female applicants for the artistic-director opening that eventually went to Dewar.

In 2017, Shaw was part of a community board called Stir the Pot, which brought together third-party improvisers from across the city to suggest changes to deal with trends they were seeing throughout the larger improv community. Though Jet City staff, including Dewar, attended these meetings, Shaw observed no changes made at Jet City.

Staff Culture

Having seen Jet City from the inside, Ethan Smith doesn’t think Barber’s situation is a blip on the radar, but emblematic of its culture. “While working there I found that the public mission that they portray and the conduct that they exhibit behind closed doors is very different,” says Smith. “It’s a place where you’re worked very hard and when you ask for support you don’t get it. It’s a place where anger runs rampant. It’s common for people to be shouting every day.”

Smith says that upon being hired as the JCI marketing and communications manager he thought he’d landed his dream job, citing how much he admires the community service Jet City does to make children and people with disabilities laugh. But the office culture quickly soured him on the prospects. While he self-identifies as a sensitive person, he was told frequently to “grow a pair” and stop being so emotional when the yelling got heated or when Dahlgren would take out his anger by destroying file cabinets.

After a May 2018 meeting at which Smith had an anxiety attack that left him trembling and teary, he says Dahlgren told him “that I make the normal abnormal on too frequent a basis. And that I’m inappropriate with my emotions. I’m allowed to be emotional to a point, and this is the point.” He left the job that day, told JCI Board President Jess Main that the staff needs anger-management and sensitivity training. He also suspects he’s been blacklisted from Jet City by the staff.

For Smith, the root of the problems is clear. “I would say that the men on the staff are the problem. It’s primarily a white male staff, primarily older. I feel as though they’re angry and a little out-of-touch. I feel bad for them in a way, because they romanticize the past. They talk a lot about when they were young artists, how people would line up around the block. And now that’s not happening for them, and I see that anger in their actions.”

Jet City players have also raised the issue of suspect financial decisions by Dewar. When Barber volunteered to put on a free workshop for Jet City volunteers, she says she didn’t want to be paid because JCI often cites costs as a reason for not doing things of that sort. She says Dewar told her to take a paycheck from JCI and then donate it back to the theater so that there’d be money going out and coming in on the books, making the nonprofit eligible for bigger grants. (Another player who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation confirmed that they were asked to do the same thing by Dewar.) Additionally, after Smith commissioned a season’s worth of poster art from an online freelancer for $600, Dewar asserted they needed a more professional local artist. Dewar then upped the art budget to $6,000, which Smith saw as a misuse of funds that could’ve been used to beef up advertising campaigns, and said he’d hire an artist he knew—who turned out to be Dewar’s sister-in-law.

Board Involvement

On November 13, the day after the post-rehearsal Q&A, Dewar sent an email to JCI players acknowledging that two reasons presented in the case against Barber—the Exit 192 conflict and the cancellation of Minority Report—were not valid. He admitted the Pitch email was “unprofessional,” but asserted that he never communicated with her that if she didn’t continue the conversation she would no longer be welcome at the company. This message was not sent to Barber, who had to get it through friends at JCI.

The Jet City Board of Directors didn’t release their statement on the situation until January 22, 2019, roughly three months after the Dewar/Downing SFIT meeting. An email sent to JCI’s “Family” email list boiled down the problem to miscommunication without giving specific details: “The performer in question raised issues of concern with a staff member, which led to that staff member requesting an in-person meeting before the performer would perform again at the Theater. A condition of this sort is not within the authority of any staff member.” It goes on to say that the board is reviewing the code of conduct and methods for providing feedback. It also states: “To be clear: This performer is an ‘Emeritus’ member of the Company, with all the rights and privileges of any other Emeritus. This includes the right to play regular shows, as well as the right to audition for shows and to participate in guest performances.”

At no point does the statement address the falsified reasons presented against Barber or even mention her by name. That irked Barber, as the board specifically asked if they could name her in the statement and she granted them permission. In an email from Board president Main asking “Would [you] care to be mentioned by name or not?”, Barber responded, “Feel free to use my name in any capacity you would like to; as long as it’s factual, I’m an open book. I just don’t want the specific root actions to be glazed over.” The board interpreted the response as a reason not to use her name, feeling she would not be satisfied with what they presented. “I found it interesting that my stipulation on using my name was truth, and they decided to not use my name,” Barber says. “All I want was an apology and some sort of accountability for the men that abused their power in a nonprofit organization for their personal vendettas.”

Among JCI staff and board, Seattle Weekly was able to interview only Board vice president Brian Muchinsky. Seattle Weekly had an interview with Dewar set up, but on the day of the interview he canceled via email, saying “I believe the Vice President of our board, Brian Muchinsky, has been in contact with you and for the time being he will be speaking on behalf of our organization.”

Jet City’s stance is that the issue with Barber and Dewar was just miscommunication. While Dewar didn’t have authority to ban Barber or put conditional requests on a groups for SFIT, there have been no public ramifications for doing so or presenting false reasons to justify it. The board says it fully supports Dewar going forward, and is still hopeful Barber will return to Jet City as an emeritus cast member.

Barber has made it very clear that won’t happen. And she still feels as if she was never in the wrong and has yet to receive an proper apology from Jet City, as they’ve kept her out of the loop almost every step of the way. The board requested Barber not to speak to the press, and inquired if she was seeking money to “drop her claims” in order to avoid litigation.

Currently Barber is focusing on Exit 192, which will soon be opening an improv school at the Historic Everett Theater. For Barber and others Seattle Weekly spoke to about Jet City, the damage has already been done. They view major staffing changes as the only possible solution to the systemic issues.

“The pattern of behavior is with the same people in the office,” says Shaw. “The women that are currently employed by Jet City… don’t really hold any power. So even saying, ‘Just bring in more women to the office or bring in more diverse people with new ideas,’ that cannot work with the same individuals working there. Unfortunately, the only solution I see is to do a complete overhaul of the administration.”

“I worry about the leadership of the place,” says Smith. “I worry about them not listening to the people that really matter and are going to squander the whole thing.”