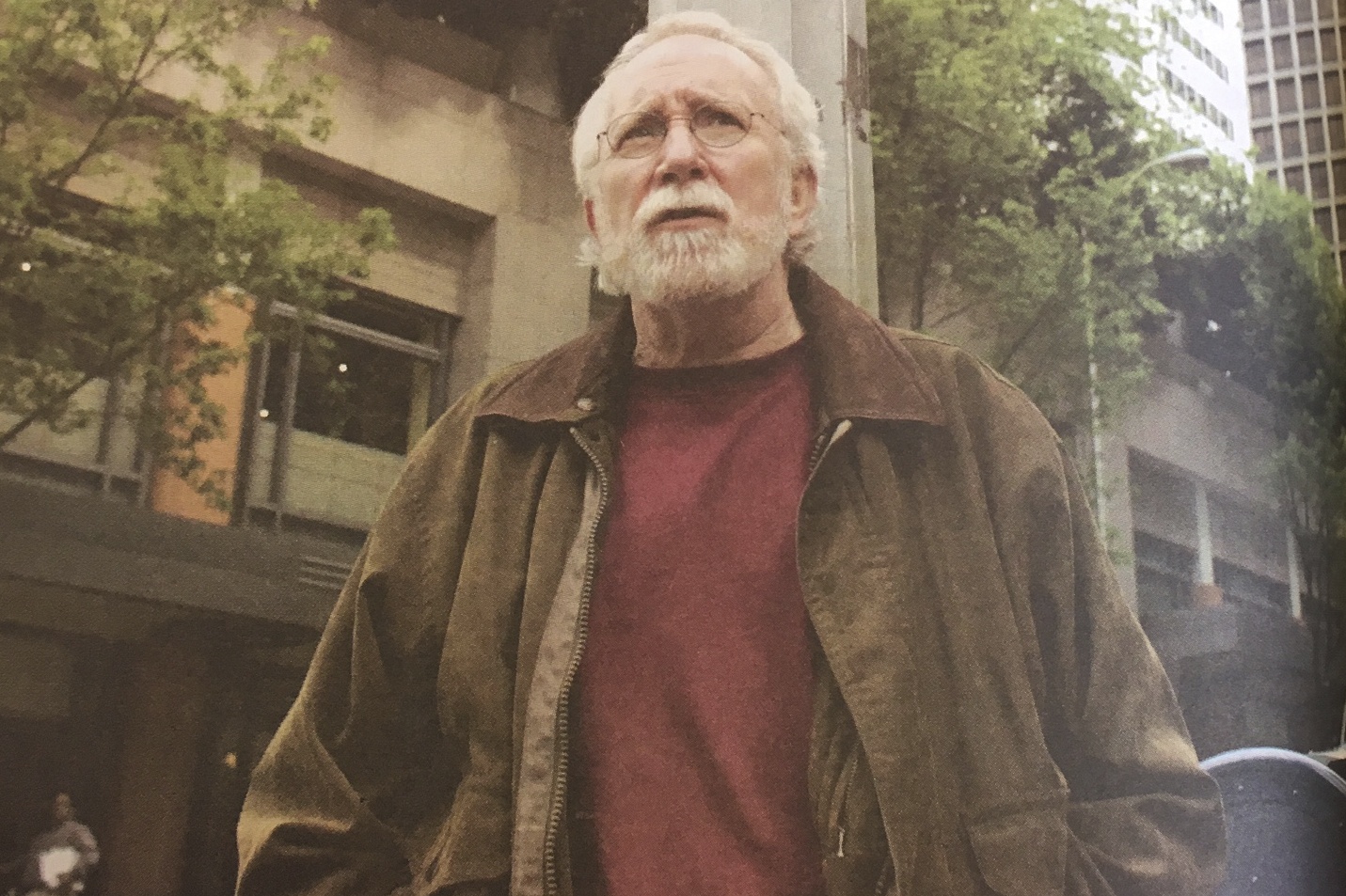

Recently, Seattle’s homeless crisis was thrust into Washington state politics after two Republican candidates for state office weighed in on how they would deal with the issue. Standing in front of rows of tents in City Hall Park, Republican candidate for governor Bill Bryant spoke out on October 10 against a new City Council bill that would require that the homeless be notified before encampment sweeps. Bryant said he would have a zero-tolerance policy toward encampments in Washington.

Bryant wasn’t the first to announce his policy toward homelessness in a camera-ready manner. Last month Republican State Sen. Mark Miloscia, who is running for state auditor, posed in front of a homeless man resting on the sidewalk on Broad Street and Third Avenue and promised that he would withhold homelessness funding for local governments that didn’t follow state standards on encampments.

Given that their lives and living arrangements are now part of the statewide conversation this election season, will the homeless in Washington get a chance to vote on candidates and policies that may impact them?

The homeless face challenges to voting, starting with the fact that, well, they’re homeless. Not having a permanent address can make it difficult to receive a ballot. “I’d consider that the biggest barrier to participating in the election process, in addition to the challenge of limited Internet access (thus limiting educational opportunity) and the unpredictable nature and schedule of day-to-day life on the street,” Meredith Hastings, spokesperson for youth shelter New Horizons, wrote in an e-mail.

At several shelters, such as the Union Gospel Mission downtown, homeless residents can list the shelter they stay at as an address. At Roots, another young-adult shelter, residents can also list the address of one of their service providers, such as the place they eat, sleep, or get health care, according to Kristine Cunningham, the shelter’s executive director.

Even with an address to list, the process isn’t necessarily smooth. “It’s a mess,” Cunningham says. “Service providers don’t always have the capacity to be a really good post office and make sure every piece of mail gets through to the right person.” With Washington’s mail-only voting, not getting your mail means not getting your ballot.

Linda Mitchell, spokesperson for Mary’s Place, a shelter for women, children, and families, lists the many barriers to voting aside from not having an address. In addition to their immigration and refugee status (the shelter has several such families, who don’t always know if they can vote), the homeless may not know if it’s possible to vote with a criminal record (it is); how to register or why it’s important; whether they’re a resident of Washington; and what issues are at stake on the ballot.

The people experiencing these barriers, of course, have other things on their minds, Mitchell says. “When you’re struggling to find housing and you’re living in a shelter situation, figuring out where to find a voter-registration form is probably not the highest priority of the day,” she says. To lighten the process, Mary’s Place plans to hold a voting party with shelter residents in November, with a field trip to a ballot box and an American-flag cake.

To help overcome some of these barriers, King County Coalition on Homelessness produced informational brochures for the homeless about exactly how to vote. Meanwhile, King County Elections works with local organizations to spread voting information among the homeless. This year there will be three accessible voting centers for the homeless and anyone else who wants to vote in person.

Kendall Hodson, Chief of Staff at King County Elections, acknowledges that lack of voter education is a problem among the homeless, but points out that this is also true of the population as a whole.

Barriers to voting aren’t just logistical—there’s also the problem of people feeling disconnected to the political process. “Unfortunately street culture is not one that encourages people to be publicly passionate about civic engagement,” says Cunningham.

The young adults at Roots sometimes need some prodding and encouragement to get involved with voting. But once the conversation starts, “they realize they actually know more than they think and that they actually care a little more than they think.”

When the issues are framed in terms relevant to their lives, Cunningham says, youth are more excited. These include issues like homelessness itself, the way the criminal-justice system treats youth, and LGBTQ rights (a third of the young people at Roots are LGBTQ, Cunningham says).

It’s unclear whether homelessness’ prominence as a political issue this year will drive more homeless people to vote. A UGM spokesperson says there hasn’t been an uptick in people getting involved in voting this year; Hastings, at New Horizons, says it’s been Trump, not Bryant or Miloscia, who has gotten a lot of people there talking.

“It’s kind of sad that when we pride ourselves on our democracy, the people who are most impacted by public-policy decisions are often the last ones to know about how to engage in that conversation,” Cunningham says. “We have all these intermediaries that try to build those bridges for the disenfranchised folks, when wouldn’t it be better to have a system that actually creates enfranchisement?”

news@seattleweekly.com