The music created by Shabazz Palaces is otherworldly. The studio albums and EPs, two of each, that the Seattle experimental hip-hop duo has released since forming in 2009 contain grand tapestries married to coded lyrics that appear like hidden gems in a maze. The veneer of space ingratiates itself into the music, conjuring both images of black ancestry and the allure of a galaxy far, far away. Such imagery informs the group’s entire identity; the two members, front man Ishmael Butler and instrumentalist Tendai Maraire, taking the stage dressed in resplendent, colorful dashikis, thick gold chains, and sunglasses straight from the wardrobe design notebooks for Blade Runner.

Butler is seen by both critics and fans as a kind of charismatic mystic, his persona an extension of the music, his mythology perpetuated by a tendency to be vague and elusive in interviews. And people have a lot of questions for the man. Well-known for his previous role in the popular ’90s hip-hop group Digable Planets, Butler’s persona underwent a radical reinvention—somewhere between winning a Grammy for the Digable single “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” and his re-emergence at the helm of Shabazz Palaces as Palaceer Lazaro.

The latest from Shabazz Palaces shows no signs of lifting the starry veil. In parallel narratives on two new LPs, Quazarz: Born on a Gangster Star and Quazarz vs. the Jealous Machines (both scheduled for a July 14 release on Sub Pop Records), the listener follows Quazarz, a being from a distant planet, down the opening stretch of Seattle’s 23rd Avenue and through a place called The United States of Amurderca. The alien is sent here to study the land’s art, music, and culture. Like much of Shabazz’s work, the albums possess an astral enticement, free-floating sonics married to grooves well worn into African-American music. The styles are bountiful and ever-changing: thumping house and techno, shuffling jazz, sun-kissed funk, smoothly laconic R&B, Technicolor soul samples, thunderous (and bass-heavy) ’80s-inspired hip-hop. Both lyrically and musically, they’re a singular take on an experience common among black people in Seattle and in America as a whole.

As fantastical as Quazarz’s journey seems, it is rooted in reality. That most fans will miss this fact is forgivable; Shabazz Palaces’ ideas are often dramatically overshadowed by the inventive and celestial soundscapes that surround them, typically tagged as “afrofuturism.” Like most critical shorthand, it’s a limiting descriptor at best. The heart of Shabazz’s music—like the heart of most artistic forms, the kinds that truly resonate with people—exists in events, both tangible and psychological, that have been happening for centuries. When the future is referenced explicitly, it shows a world not all that distant from the past.

Still, Butler prefers to leave his music open to interpretation—his perspective on the meaning of his lyrics is not as important to him as the listener’s. In an age where lyric annotation websites such as Genius offer concrete explanation of both references and, occasionally, the artist’s own intent, to see a musician uninterested in putting his own meaning at the forefront is refreshing. He has mentioned in many interviews over the years that his music is impressionistic, that his lyrics leave the door wide open to multiple meanings.

I wanted to talk to Butler about his own outlook on life, the Seattle he was raised in, and his take on both the future and the present. I hoped his answers would unlock the meaning only hinted at in the labyrinthian world his words and music have created. But before I could unlock the labyrinth, I had to be buzzed into the locked front door of Sub Pop Records.

A table stretches the distance of the conference room at Sub Pop—a label Butler emblematizes not only as an artist, but also as an A&R representative. True to form, Butler is wearing a sweatshirt that looks like a panoramic drawing of space, resplendent with stars and nebulas. He gregariously greets his publicist and me with an easy smile, as though we’re old buddies.

As someone who has met Butler before, chilling out at a Toro y Moi show with a few of his friends, it’s safe to say when you share a room with him, his coolness borders on mythical. There’s affability, depth of knowledge, and the occasional freewheeling joke. Coupled with the lofty ideas of space and black identity, his daring musicality, and his tendency to create a very specific type of art without giving his own definitive take on it, Butler offers the impression of a complex artist—a complex man—but not an unknowable one. To know him, you must know where he comes from.

Butler was raised in Seattle’s Central District, a place he says felt like a small Southern town at the time. “Everybody [in my neighborhood] that grew up in Seattle [in the 1970s], their grandparents were from Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas,” he says. “They migrated up here with the promise of opportunity, of a new life. And so a lot of us, we were born to explorers and frontiersmen and curious, brave people that set out to places unknown, looking for adventure and to settle in a new territory.”

The story of Quazarz is informed by that adventurous spirit, as the interplanetary traveler sets out to immerse himself in a new culture and observe a self-obsessed and violent world. You can hear its darkness in the bass lines of the darkwave surge “That’s How City Life Goes” and the sleepless bounce of “Late Night Phone Calls.” “Parallax” draws a straight line between high-end fashion labels and the pollution of the African coastline while lamenting “alternative facts” as a real term in the realm of intellectual discourse.

In the real world, the 23rd Avenue that Butler’s hero explores still feels a significant distance away from the full sweep of gentrification that has come to define Seattle over the past decade. Starting at the intersection of Spokane Street, it appears to be a quiet, unhurried, reasonable place to live. It’s certain the houses for sale are pricey, being in Seattle and all, and signs of future development abound, but the aura of 23rd—at least the stretch just south of East Madison—still doesn’t match that of areas just a few miles north. There’s Parnell’s Mini-Mart, its barred windows showing a veneer of grit disappearing from Seattle. Farther north is Ezell’s, where Butler observed the crows lining the fence outside on “Motion Sickness” from Shabazz Palaces’ second album, Lese Majesty. There’s also the Central Area Youth Association, name-dropped on “Since C.A.Y.A.,” the opening track on Quazarz: Born on a Gangster Star.

“Welcome to Quazarz” communicates the modus operandi of Amurderca (“We post-language, baby/We talk with guns, guns keep us safe”) before delving into a chorus that plays on the slang expression “killing it.” At the end of the song, when Butler intones, “We kill parties,” it sounds cool. When he repeats the phrase “We kill” right afterward, it sounds much more foreboding. “Shine a Light” conjures images of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse with an eye on police officers gathered on the corner. “The SS Quintessence” renders a commonplace image into striking imagery: “With blood on their teeth, pigs walk on two feet/And enjoy with conceit, the last laugh.”

I ask about the culture of police brutality, a recurring theme in his lyrics. “For me, I learned early about the notion of ‘police brutality,’ with ‘brutality’ being the adjective that describes a certain faction of the police department and their ideology. I don’t separate the two,” says Butler, who is speaking to me a few days after the acquittal of the police officer who shot Philando Castile. “The police understand that they have to exercise a brutal regime against that which they deem as an opposition to themselves. Which, from the inception of what the police departments are, has been black people or black community, and specifically black men. It’s a brutalist entity.”

Butler, who just turned 48, doesn’t subscribe to the notion that police officers who kill civilians without probable cause are an anomaly in any police force. He speaks about the militarization of police as a concept and the fact that many officers are integrating themselves into civilian communities after serving in the armed forces, a situation that results in a force that he believes is trained to militarize, rather than de-escalate, hostile situations. Members of a very real white-supremacist subculture are joining police forces, he contends. They are fulfilling their own objectives, he says, some of which have fateful repercussions for citizens with little or none for officers.

Butler says police departments, the press, and communities need to investigate the lives of officers involved in instances of apparent brutality. “They never go deeper into the story. There’s never an interview with the police officer who shot this person where they’re asked point-blank, ‘What was on your mind? Who did you talk to before that? Are you involved with any clubs outside of the police department that involve police? What is your political outlook?’ There’s no history to any of these people; it’s just like a police officer is supposed to mean one thing to us.”

When asked if there is a solution, or if we as black people are destined always to be under the thumb of systemic oppression, Butler’s answer asserts in no uncertain terms that he believes a one-sided war is being fought. He cites people within the black community taking their frustration out on the closest thing to them instead of effecting a change in the system. He praises the leadership and infrastructure of the Black Panthers, and laments the void left when the party dissolved nationally in the early 1980s. “We’re all trapped in ideology, man. It’s hard to get out of that mental enslavement, that mental clutch where you have this frustration but you don’t understand it, so when you lash out, you only lash out at what’s in your reach. Rather than at the very thing that has put you in this position to have this frustration and this anger.”

In a 1970 speech at Boston College, Black Panther founder Huey Newton suggested that black communities in Oakland and San Francisco can’t truly partake in capitalism because imperialists have already centralized the wealth. Likewise, capitalism is the dark cloud that looms over much of my conversation with Butler. It’s there when we talk about our rapidly changing city. And it’s there when he bemoans materialistic rappers making plays for financial status. It’s a problem without a clear solution, Butler says, because capitalism is inescapable. “I think [it has] been effectively manipulating everyone’s mind, not just black people or cultural groups,” he says. “The system isn’t something that needs to be conquered—[the general feeling is] it just needs to be played and manipulated for your own benefit. Instead of anybody having a communal sense, everybody looks at the system like, ‘Yeah, but OK, that guy right there, he played the system and now he’s rich. And he’s on Instagram with a boat. So instead of me [rallying] against the system, let me figure out ways to work the system, because all I really want in life is something for myself.’ ”

Shabazz Palaces’ most direct critique of this system comes in multiple references to rap artists who flagrantly disregard hip-hop’s art and ethnology, engaging with the form only as a way to pad their business portfolios. “Self-Made Follownaire,” on Quazarz vs. the Jealous Machines, continues this line of thought, ruminating on what Butler calls “a threshold of immediate consequences” brought by social media’s instant feedback and technology’s role feeding a thirst for fortune and fame that disregards artistry and history. When the topic is broached in the conference room, Butler says, after a deep exhalation, “I feel like I can tell within a few bars whether you’re approaching it from a passionate place or … sort of a commercial place. If that’s your choice, so be it. I do have thoughts on that choice, because I don’t think people should pursue things that aren’t necessarily their passion. I think that creates an imbalance in society.

“And we’ve seen that, where it’s kind of like a gold rush towards money and fame. And cats are like, ‘What’s one of the easiest ways or the most prevalent ways of doing it? Oh, hip-hop music, let’s go that way.’ So you get, just like in a gold rush, a whole bunch of motherfuckers trying to tear the ground up for a little bit of jewels. It makes an atmosphere … it’s like living on a garbage heap, kind of. The air is bad, the smell is bad, it’s just not a healthy environment for good things to flourish.”

In “30 Clip Extension,” Butler takes on rap capitalists, narcissists, and shallow avatars of black suffering. They hire ghostwriters and are guilty of “puffing out their tattooed chests.” Though the topic wasn’t broached in our conversation, the Quazarz press materials allude to “Drake World” and the “Migosphere.” Butler mentioned Migos among the rappers whose music he currently enjoys, but Drake did not come up. Make of that what you will.

The gold rush Butler describes has created a climate where some very talented hip-hop artists are reluctant to refer to themselves as rappers. Take a recent New York Times interview in which Kendrick Lamar said he preferred to identify himself as a musician and a writer. “Maybe they feel as though it’s too much of a compartmentalization,” Butler says of this recent turn, “or that when people talk about rappers, they come with a set of predetermined notions that maybe these brothers feel like they want to transcend.”

Butler says he prefers for rappers to strive to expand the horizons of what a rapper can be, rather than distance themselves from the term. Around for barely four decades, hip-hop is still a young genre, draining less than half the hourglass of other culturally rich and historically black music genres like blues and jazz. The form expands daily, regardless of an outsider’s perception of its horizons. Butler—who describes himself as an artist across several different media, of which rap is one—ruminates on the form with profound gratification.

Shabazz Palaces synthesizes a world of disparate elements into one clearly influenced and buoyed by rap. Butler would not say he’s helping elevate the form, though. “Rap music has been elevated to heights, to places that have inspired me to live, to get through life. Forget being an artist—rap has been around and has elevated my life, providing a context for my creative predispositions and taste. Hopefully I’m not bringing it down in any way, in anybody’s opinion. But I don’t really think about what I’m doing for it. It’s doing a lot for me.”

The notions of improvement and elevation were dominant topics in my conversation with Butler. Orange cones, cranes, and shiny new buildings dot the landscape that surrounds the Sub Pop offices in the heart of the city. The ever-growing tech boom has brought rapid change to the city, helping to hike rents substantially in service of an industry that seeks to forge an even closer bond between us and our devices.

Since moving back to Seattle in 2004 following a 17-year stint on the East Coast (New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore), Butler views the change in the city—accelerating each year—with some wariness. “Progress doesn’t mean one thing,” he says. “Growth doesn’t mean one thing. Everything can’t boil down to money. If your ideological approach to growth and change is the amount of money that’s being generated, then it’s going to cause a lot of cultural problems and cultural deficiencies. And I’m not into it enough to know exactly what’s going on, but from the way things look, it kinda looks like that is where Seattle is coming from right now. It’s very expensive, but culturally, I wish it had maintained some of its uniqueness. It just seems like we’re rushing full speed ahead. To what, I’m not really sure. But I like Seattle, I believe in Seattle still. Seattle is a dynamic place. And it’s my home, so I love it in a way that is unexplainable almost.”

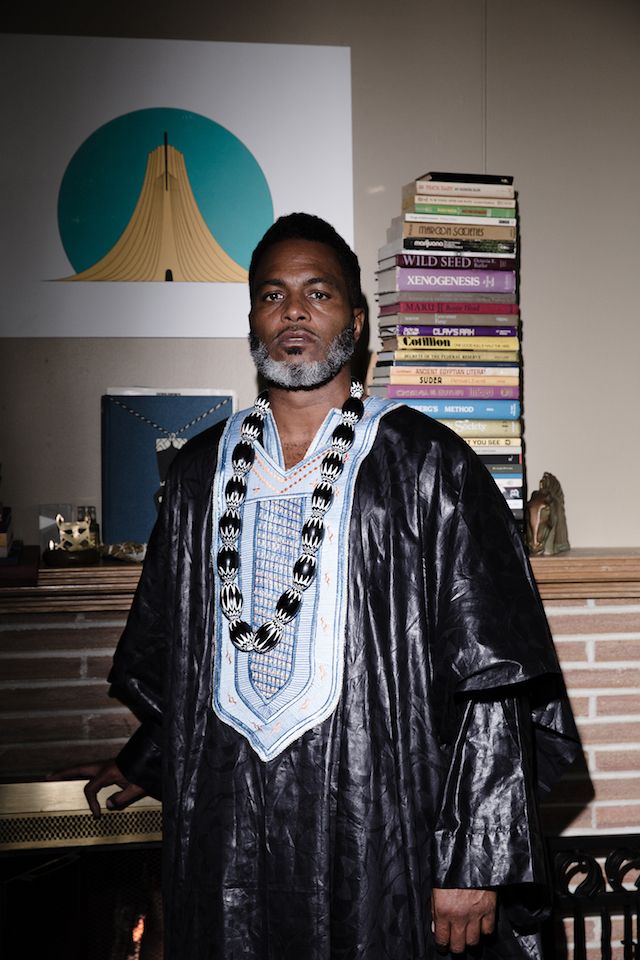

Butler with Shabazz Palaces instrumentalist Tendai Maraire.

Butler with Shabazz Palaces instrumentalist Tendai Maraire.

Broaching the topic of “newness” provokes consideration of whether or not Seattle is obsessed with the concept. Butler feels that few places are expressly apprehensive about modernity; he thinks that in America, “newness” is culturally analogous to “improvement.” A recurring thought springs up again: “Just because it’s a reality doesn’t mean it’s a truth.” What we see in front of us, what we hold in our hands, isn’t necessarily emblematic of our humanity and our beliefs, Butler says. Reality does, however, tend to affect our relationship with personal truth, and it has the power to change our habits.

This is where “the jealous machine” comes in. On “Gorgeous Sleeper Cell” from Quazarz vs. the Jealous Machines, it is referred to as “my glowing phantom limb.” Decoding this is not difficult: Butler is rapping about our smart phones and their ability to enable an intimacy that is practically inescapable for most of us. “I try to think about it and use it the least I can,” Butler says about his own. “But I also enjoy it and notice it when it’s not around. And that makes me kinda feel like a sucker, to feel this way about an inanimate, small, very simple device. I feel like it’s controlling me. I’m always making sure it has enough to drink and that it’s protected. And it’s like, What the fuck, man? What is this thing, man?”

Butler says he thinks humanity’s relationship with its phones represents an excess. “We haven’t even thought about how [the amount] we use it is going to affect what we become as human beings in a very short amount of time.”

He presents a hypothetical: “A little kid may be in a corner and playing or something, doing something cute. The first thing you do is … [pulls out phone like he’s taking video]. And so the kid is learning life and seeing what Mom’s up to, and she notices, like, ‘Damn, every time I do something and the smile goes on my mom’s face, I see this thing.’ Or, ‘Maybe if I do something and the thing don’t come up, then maybe it’s not a cool or cute thing.’ ”

Butler is aware of the profound impact that early impressions can make. He recalls his father bringing home Space Is the Place, Sun Ra’s visionary album, released in 1973 when Butler was 4. The album would become a cornerstone of his artistry. “So from there, to Parliament, to the Last Poets, the music and the culture I was raised in, the notion of space and aliens was something that I just took as a fact,” Butler tells me. “I take what Sun Ra said about him being an alien and a being from Saturn or something like that, I take that as a fact. That’s not sci-fi to me. George Clinton, who can sit down and rattle off a poem at the top of his head for five or 10 minutes, that could be very intricate, very political, funny, sexual. And you’d be like, ‘OK, where’d this guy get the ability to do this from?’ I mean, well, he told you, he’s a motherfucker from outer space! I take all that literally, man.”

That Ishmael Butler is a human being and not a motherfucker from outer space is obvious. Yet his afrofuturism is no less powerful than his forebears. Like all artists who get tagged as “afrofuturist,” Butler, with Maraire’s help, is giving form to a very earthbound idea: Being black in America is much like being from another planet. No matter what we do, we’re always going to be besieged with body language and subtle suggestions that we don’t “belong” here, regardless of how many of our ancestors were uprooted from our native lands and brought to this place.

As the saying goes, we’re living in the future. And in some ways—certainly in the realm of politics—it feels like the beginning of a dystopian novel. In others, it’s just representative of our day-to-day lives—lives for which a generation ago, cell phones were too big to fit into a pocket. Now we’re contemplating the psychological effects that capturing every moment through a phone’s camera lens has on our children. We’re seeing police kill civilians through that same lens. The future is still an abstract concept; who knows what advances and regressions we’ll experience in 10, five, two years? The music of the afrofuturists offers a bridge, then, from that past to an imagined future that must be experienced within the very real now. Listening to the music of Shabazz Palaces, at least, offers a valuable takeaway: The present and past were once the future; neither are all that far away.

music@seattleweekly.com