Barbara Kopple’s new documentary follows Woody Allen through Europe as he tours with his jazz band. New Orleans jazz, he says, “rings an inexplicable bell in me. It’s like taking a bath in honey or something.”

Films need more space in them. (On this notion is built many a cinephile’s love of French movies, which allow for lots of breathing room.) Music films provide that space with their extended concert footage, which gives viewers time to make their own connections and establish a more personal relationship with what they’re seeing. As the musicians play, they make a great lake of non-narrative space within the narrative of the film, the same way Lake Washington lies within the city. Concert footage brings all narrative to a stop, and we find ourselves in an undefined place. In the best films, story is replaced by the sheer joy of watching someone do something they love really well.

Wild Man Blues

directed by Barbara Kopple

starring Woody Allen

plays 7/17-23 at the Varsity

Music Film Festival

plays 7/17-30 at the Grand Illusion

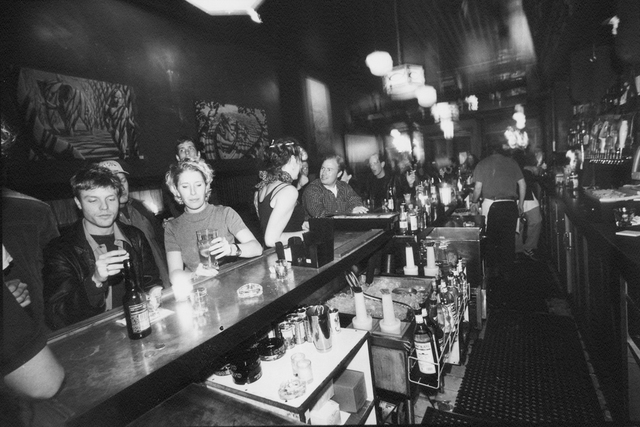

Kopple (Harlan County, USA, American Dream) pulls this off in Wild Man Blues. When Allen’s onstage, he’s not cracking wise, he’s not tortured by doubt, he’s not holding hands with a very young woman; he’s simply a guy playing clarinet. Woody Allen is a man whose persona is etched on our consciousness, but as we watch the concert footage of him noodling along on his licorice stick to “Down by the Riverside,” we actually forget who he is. We forget his story because we are lost in the pleasurable, living space of the concert film.

There are other pleasures here, too. Allen extemporizes on whatever falls in his path. He’s a knee-jerk joke-maker. He regards the bass player putting his gigantic stand-up bass into its equally gigantic case and says, “They should’ve told him when he was a kid… y’know… flute.”

And of course we finally get to observe Woody on film with Soon-Yi—a prospect anticipated by many with dread. At the beginning of the film, the two seem uncomfortable being filmed. Over breakfast they make stilted conversation: “The shower was excellent, wasn’t it?” “Yes… great pressure.” Kopple, whose direction is usually unobtrusive and opportunistic, here uses a witty formal framing device, catching the two in a static shot, symmetrically seated at the breakfast table. But as the film continues, Soon-Yi relaxes and emerges as a funny combination of boss and brat whose pragmatism comes as a tonic to Allen’s cultivated neuroticism. While Woody’s ruminating on the meaning of it all, Soon-Yi is wondering why the waiter didn’t bring her toast.

But the real kicker comes at the end of the film, when Woody returns to New York with a sackful of trophies and medals, which he drops off at his parents’ house. The scene could have been lifted from one of his early films. His father still thinks Woody should’ve been a druggist: “I think you might’ve done better business.” Woody’s sister reminisces about how he used to take tap lessons. Mom turns to Woody: “You did a lot of good things, but you never pursued them.”

The festival of music films at the Grand Illusion over the next two weeks should provide lots of moments for free association and other loose behaviors associated with watching concerts (for a complete schedule, see Goings On, p. 54). The Rolling Stones Altamont documentary, Gimme Shelter, holds up wonderfully well—as do all the Maysles brothers’ documentaries from this period. The Altamont film is overcast with a feeling of doom: We all know how Altamont turned out, and, sadly, we all know how the Stones turn out too. The real surprise here is that since we know how each band member has weathered old age, Charlie Watts emerges as the real sex god.

Hard Core Logo, the excellent rock/mockumentary that played at SIFF two years back, is a kind of Canuck Spinal Tap, sending up the clichés and dumbness of rock in this tale of a reunited punk rock band. The leader explains the group’s mission: “It’s like, fuck you. And that’s what we’re all about.” Also on the bill is the rarely seen 1966 The Velvet Underground and Nico, directed by Warhol, shot by Gerard Malanga, and featuring the Velvets in performance before their first album was released.

The must-miss film on the docket is the Fred Frith concert documentary Step Across the Border. Though I’m a fan of Frith’s music, this German-made film turns him into a kind of Robin Williams of music, forever teasing strange sounds out of unexpected objects in a tiresomely show-offy, playful way. (I was reminded of those people who sing in the aisles at the PCC just to let you know how free they are.) Worse yet, the filmmakers try to marry Frith’s complex music to analogous images. It’s a visual language that’s been so plundered by MTV there’s nothing left but a bad smell of commercialism.

But clear your mind with the wonderful films of Les Blank, who will attend the festival. His short, handmade-feeling documentaries capture the essence of the music film experience as he travels into his beloved South, recording the doings of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Appalachian fiddler Tommy Jarrell, and the members of New Orleans’ Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club—who dress up as Indians every year for Mardi Gras, and, led by Professor Longhair, sing in a strange, made-up language. Blank has no social agenda; he simply wants to show people being transported by music. His filmmaking is that paradoxical thing: a meditation on having fun.