An overdose, a cigarette holder, Andy Warhol, kohl eyeliner, several wigs, polyester shirts, screwing in the balcony, superstars in the basement, wads of cash, handfuls of downers, tiny vials of nose drugs, the narcotic thump of “Knock on Wood,” the irrefutable spin of the glitterball: Director Mark Christopher’s Studio 54 is a palace of excess. Too bad this glitter-bedecked diva of a movie is all dressed up with no place to go. Christopher has the look down and the spectacle documented—but he’s got no story.

54

directed by Mark Christopher

starring Ryan Phillippe, Mike Myers, Neve Campbell

now playing at Metro, Uptown, Oak Tree, and others

Our guide through this Disco Inferno is blond-haloed, thick-lipped Jersey boy Shane O’Shea (Ryan Phillippe). He sees a society-page photo of his favorite soap star, Julie Black (Neve Campbell), making the scene at 54, and off he heads into Manhattan to get a up-close glimpse of her. At the door, he discovers his looks are all the password he needs to get past the rest of the bridge-and-tunnel crowd, and he’s In.

Shane is the shadow brother of Tony Manero, but without Travolta’s urgency or his dumb glamour or even his dancing fever. In an early voice-over, he describes his Jersey-bound life with his dad and siblings and high school pals: “I had to break out.” But he doesn’t break out into anything. He seems just as dull and emotionless once he makes it to Manhattan. It’s as if he emerged from his chrysalis . . . still a caterpillar.

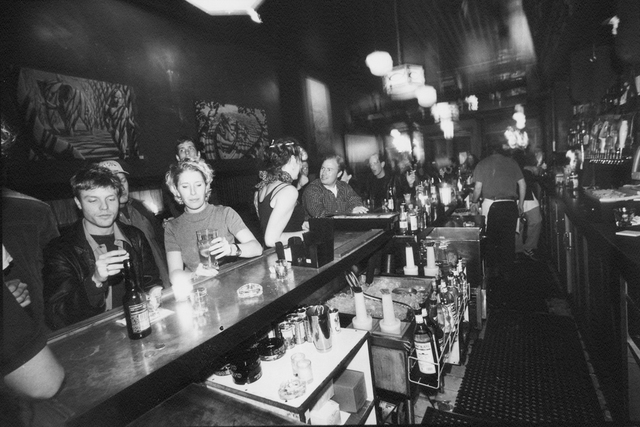

While he doesn’t become a butterfly, he does become a bartender, the apex of achievement in the 54 world, and befriends Anita (Salma Hayek) and her husband, Greg (Breckin Meyer). The plot, such as it is, hangs on the attempts of this trio to find fame and fortune under the glitterball. There are moments, as they meet with their little successes and failures, that you think, My God, I’m watching “Fame.” But Fame is a richly woven tapestry of plot and event next to 54, which just sits there

—it’s the most sedentary dance movie ever made.

Even the love story between Phillippe and Campbell, which comes late in the film, fails to create a sense of story. It doesn’t help that Hayek, Phillippe, and Campbell are all utterly devoid of screen presence. They look healthy and young and sexy, and they have great teeth, but they seem strange protagonists for a film about Studio 54, a place of self-made superstars. Without charisma their beauty begins to bore.

Mike Myers, as Steve Rubell, on the other hand, demonstrates all the demented energy of a self-made club king. He disappears into the role, becoming the Jordache-clad Rubell, wrong-headed and romantic and cynical and irresistible. He stands at the door of the club, casting a happy eye on all the people he’s excluding, looking like a cross between Paul Simon and a rat: “I can’t let you in,” he tells one desperate fellow. “You’re wearing an ascot.”

Myers has a firm grip on the tragic elements of Rubell, but the real tragedy here is that in this otherwise characterless film, Myers’ stunning performance has no context in which to resonate.

Myers’ performance and the sheer spectacle of the thing buoys the film for a while, but Christopher never slows down long enough to let us revel in the naughtiness of it all. Scene length is a major problem—there’s no variation, so the film seems to pass us by at a clip, one two-minute snippet after another. Christopher’s disco is a giant, shining toy, but he doesn’t slow down to enjoy it. You long for an extended tracking shot so you can check out the action. One image gives a sense of what might have been: the bartenders stacked half-naked and three-deep behind the bar, gyrating and squirting alcoholic liquids like marble cherubs come to life. You lose yourself in the moment—it’s heady and raunchy and beautiful. And it’s the only explicit celebration of gay disco culture in the whole film.