THE MEDIA HAVE depicted Summer of Sam both as Spike Lee’s first film with an all-white and Hispanic cast, and as his first really nasty, violent piece of work. (Those two dots may or may not connect.)

Summer of Sam

directed by Spike Lee

starring John Leguizamo, Mira Sorvino, Adrien Brody

starts July 2 at Metro, Galleria, others

More compelling is the way the film picks at the knot Lee’s been working for years: the problem of difference. And right now, after Littleton, we’re all a bit worried about people who seem different. In fact, if they’re teenagers and they seem different, we’d prefer it if they’d just stop it right now, please.

New York, 1977: The summer is hot (record highs), dark (brownouts and blackouts), and damn scary (a serial killer is on the loose). The city’s edges are growing jagged. A rumor of the killer’s predilection for dark-haired girls sends the city’s brunettes rushing to the beauty parlors, begging for peroxide. This suits hairdresser Vinny (John Leguizamo) just fine. Vinny, Guido-sharp and ready for love, takes his wife Dionna (Mira Sorvino) disco-dancing every night. And every night he seems to find the time—and the girl—for a little extracurricular activity as well.

While intertwined in a backseat session with Dionna’s cousin, Vinny comes this close to being Son of Sam’s next victim. A good Catholic boy, he is immediately consumed with fear and guilt: God clearly means to punish him for his multitude of sins. You know the old joke: What’s that bit of skin attached to the end of a penis? A man. Vinny is a penis with a Catholic-sized conscience attached.

As the bodies mount, Vinny and his paesans draw up a list of weirdos who could be—no, probably are—Son of Sam. One person emerges as their main suspect: Richie (Adrien Brody), a good neighborhood boy who went away somewhere undisclosed and came back a punk rocker, of all things. Like a peacock with a fake Cockney accent, he struts through the neighborhood flaunting his colorful Mohawk plumage and sleek black leather pelt.

Lee works hard—at times too hard, too visibly—at recapturing a time that’s clearly mythical in his mind. Some of Lee’s strongest work, especially the underrated Crooklyn, has dealt with memory. But here Lee’s storytelling is undone by his attention to the details of the past: “I’m with Stupid” T-shirts, Binaca spray, Studio 54. These are fun icons, and you can see how a director might find them irresistible. But Lee’s problem, as always, is that he needs to learn to pass up the unpassuppable. This caricaturing of an already exhaustively caricatured era only puts a layer of fat on what could have been a lean, mean moral fable.

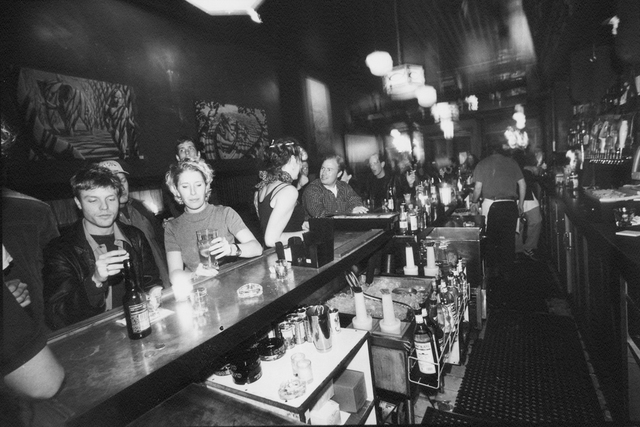

Leguizamo’s Vinny is a comic soul in torment, but Richie is the real soul of the film, all dark compulsion and goofy, adolescent attempts at self-expression. When his band, Late Term Abortion, plays CBGB’s, his bandmates all pose coolly while Richie bangs away Pete Townsendstyle on his guitar and can’t keep a loopy grin off his face. D. Boon of the Minutemen once sang the lyric, “Punk rock changed my life.” Richie is a guy whose life is being changed.

But, alas, not always for the better. Richie must pay for his difference, as Vinny and his friends turn vigilante. The neighborhood convulses in a communal paroxysm of fear. The local godfathers throw a sort of fear party during a blackout one night: kids are organized to roam the streets with baseball bats, whaling on strange cars that dare enter the neighborhood. In this anything-goes panic, it seems reasonable to persecute someone as weird as Richie.