The book, we keep hearing, is on its way out. Whether it’s the fault of Kindle or the Web itself, we will, we’re told, read differently in the future. The Book Borrowers: Contemporary Artists Transforming the Book, a show organized by the Bellevue Arts Museum, is less about reading books and more about reading into them; less about their contents and more about their usefulness as media. Books, after all, make good raw materials: Paper and cardboard are malleable, their pages take color well, and the patterns and repetitions in found text and imagery offer a rich vein to mine. Paper also straddles the line between art and craft nicely in this show, which features 13 local and international artists.

A book is not only a knowledge-bearing vehicle, but a thing with a botanical past. When you first enter the exhibit, you’ll encounter what looks like a cross-section of a fallen tree. The woody center of the two-foot-wide slice is composed of bound pages curled into rings; red hardcovers form the bark. This is Hawaiian artist Jacqueline Rush Lee’s Core: Cross Section View Slice: Volume Series.

Also with “core” in its name, and also working with the book’s organic origins, is Core 4, a sculpture by Georgia-based Brian Dettmer—an upright stump formed from one book. The pages of what looks like a dictionary have been cut, with images preserved to present a sort of natural history. We see diagrams of a peach, a saber-toothed tiger, and a dinosaur. This altered book is a relic, an object that both destroys and preserves its very bookishness.

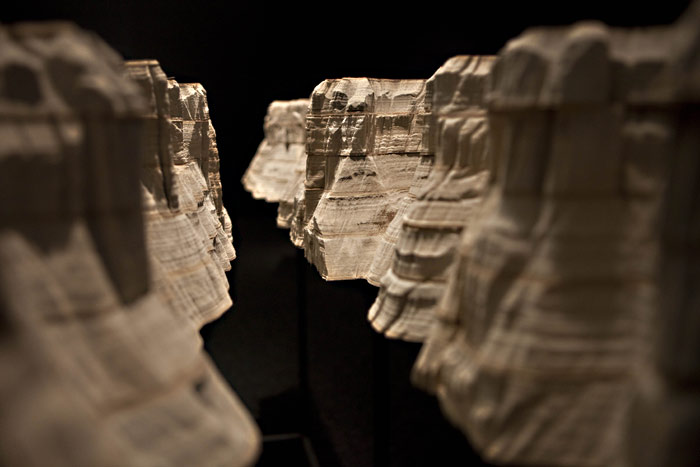

The most striking piece in this show is a four-foot-long replica of the Grand Canyon sandblasted from 80 volumes of Encyclopedia Britannica. Eight stacks of heavy, hardbound books are set five high, creating two facing rows. The piece, La Grande Bibliothèque, is presented at about chest height; you look down into the canyon. The hardbound covers create horizontal strata, a nod to the excavation of facts that went into compiling these tomes.

Hailing from Quebec, the artist, Guy Laramée, has created a beautifully rendered sculpture that makes landscape out of received knowledge. This old-school research tool may have been made obsolete by online resources such as Wikipedia, yet the artist suggests that we may be destroying more than paper here. All the expert research, careful writing, and editing that went to create these reference books has been pulped.

Elsewhere, New York–based Noriko Ambe has carved round openings into books to create strange topographies, maps, and figures whose faces have been distorted and exaggerated into abstraction. Ambe cuts into photographer Neil Selkirk’s book 1000 on 42nd Street to create A Thousand of Self, in which a black boy and white man each wear several eyes, swimming in numerous rounded cuts on their faces. It’s as if the personality of each figure has been shaped by what he has seen and read, or, more literally, by all the other people in the book itself, which depicts the many faces of New York City’s 42nd Street.

For the most part, I was less drawn to the local artists in the show, with two exceptions. In a strikingly simple work, Alan Corkery Hahn stitches two open palms into facing pages of a dictionary. The black thread is like a line drawing, in a minimal style that reminds me of Diem Chau. The pages are printed with M-words from “morning” through “mother” to “mouse.”

And for SNPS/Slips No. 2, 12 and 6, Jane Lacey has installed three rectangular cross-sections of pages into a paper frame. It’s as if a book has been sliced lengthwise, and you’ve been given the sides of the bound pages to read, a cloudy mass of black on white. This work offers a more abstract use of the book, a more textural one. Lackey also embeds a first edition of a dictionary in the flat frame, but removes all but the cover and title page. We see a sheet of gauze and a cracked binding, and strain to read the title backward through the reverse of the title page. The book has been stripped.

Lackey printed her own nonsense text onto the reclaimed books—”that kid was escorking us moving is no picnic when/you’re packing I can’t cook worth a cam bake my bike telefathic fax we’ll,” etc.—but it talks to us. Here’s one work to read about reading. Within splayed examples of a book’s physical presence (text, cover, binding), this piece is the only one, in bringing the action of a book to the viewer, that evokes the pleasure one gets from words.