I WAS CLEANING my desk and found the following phone message in the hand of a long-departed editorial assistant: “Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd is threatening to sue us, saying Geov Parrish can’t call him a racist and a moron without proving it.”

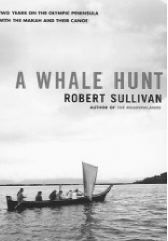

A Whale Hunt

by Robert Sullivan (Scribner, $25)

Ah, yes. It brought back that heady time in the mid-to-late ’90s when the Makah Indian whale hunt brought out the racist moron in a lot of people, journalists included. It was a huge local story with international implications: a small tribe on the tip of the American continent asserting its treaty rights to hunt gray whales—rights to be protected and enforced, if necessary, by the US Coast Guard. Opposing them, a consortium of battle-seasoned environmental activists, armed with ships and kayaks, determined to stop the erosion of whale protections worldwide, not to mention the murder of a nameless “Willy.”

The man-bites-dog element for the media, of course, was that greens and Native Americans are usually allied. Environmentalists often proclaim to be moved by the values of Native American earth stewardship. In this case, though, strange bedfellows were the norm. Here the Indians sought the aid and comfort of whaling specialists from overseas, including Japanese whale hunters, known for their brutal hunting of whales for food and “science” (they recently requested permission to dramatically expand their take to include sperm whales). And in the environmentalists’ corner were such oddball right-wingers as Republican Congressman Jack Metcalf, usually no friend of the tree-hugger crowd, and Seattle cell-phone billionaire Craig McCaw, who offered to pay the Makah not to hunt.

Such a volatile realignment increased the natural tensions, as both sides had to come to grips with mixed feelings, scrambled loyalties, and a sense of betrayal. There were protests, blockades, confrontations, death threats, and, at one point, the National Guard. And over-flying it all was a squadron of TV choppers hoping to bring you the whale slaughter or native-green confrontations live and in living (or dying) color.

That media coverage—and the war of rhetoric on the editorial and letters pages of Northwest newspapers, including ours—missed much of the story. The debate was largely reduced to screeds and the players to talking heads: tribal leaders defiantly insisting on their right to kill or activists accusing the Makah of the moral equivalent of crimes against humanity. It was Butchers against Angels, Noble Savages against Racist Yuppies.

THERE HAD TO BE a real story underneath it all, one about ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events. Portland writer Robert Sullivan decided to find that story and wisely chose to tell it in a book where he could take his time and follow characters, watch them develop, change, and reveal themselves as they moved through tumultuous events. The result is A Whale Hunt, Sullivan’s account of the Makah whaling imbroglio, told by one who spent months living in a rude, sodden hut on the Makah Reservation. During his months there, he followed and became close with members of the whale hunt team as they prepared physically and spiritually to become hunters like their ancestors. He even participated in some of their preparation rituals, like treading water in the frigid waters of the Straits. (Note to Robert Sullivan: Have your testicles descended yet?) He got close to whale hunt captain Wayne Johnson and documents the local and personal politics behind the tribe’s attempt to redefine itself. He also interviewed many of the protesters, some in their native California lairs, and visited the gray whale breeding grounds of Baja—all to get a sense for the people and animals involved in this colossal collision of cultural forces.

Sullivan wrote a previous book, The Meadowlands, a close-up look at one of America’s most notorious dumping grounds—truly the Yellowstone of toxic waste sites. In it, though, he found nature at work, in a sense reforming itself through and around man’s cruel treatment. It’s a book that changes the way you look at nature and the often artificial and arbitrary boundaries we draw between it and ourselves.

In A Whale Hunt, Sullivan is again looking for insight in detail, exploring the tender areas between how man both abuses and worships the natural world, often simultaneously. Can the men who hunt and slaughter whales love them too? Is it right to value whales more than people? How can a tribe reconnect with its ancestors when the world has changed so much that harpoons have been replaced by high-powered rifles?

To help him in his search for meaning, Sullivan uses Herman Melville’s Moby Dick as a subtext, peppering the book with footnotes riffing off of themes and facts from the book and the life of its author. For example, while telling us that the Starbucks coffee chain was named after the character Starbuck in Moby Dick, he also tells us that the original whale the book was based on was named after an island, Mocha. Mocha Dick, he was called. Cute fact, but I found Sullivan’s use of Melville a distracting, unnecessary device. His attempts to overlay the book on the Makah whale hunt, searching for modern-day Ishmaels, Starbucks, and Ahabs, are less insightful than annoying: He has plenty of story to tell simply on his own.

SULLIVAN GIVES US an inside peek into life on the Makah reservation in Neah Bay, a frumpy town on the Lower 48’s westernmost point, a place not unlike an Alaskan village. He brings alive its people—not as quirky Northern Exposure-type characters, but as real folks living lives that are at once recognizable (pickup trucks, fishing, and beer) and yet rooted in an ancient culture, the reminders of which are all around: the relics from the archaeological digs near Cape Alava, the residual potlatch ceremonies that play out in community events, the ancient clan loyalties that persist to this day. He walks us through strange country, no more familiar with it than we, and tells us what he sees.

The most compelling part of the book is its climax, his day-by-day, blow-by-blow account of the final hunt for the whale. He puts us in the canoe with the hunters and describes in a way that TV never caught the incredible danger, bravery, stupidity, and luck that attended both adventurers and their adversaries. I found myself gripped with the details, for example, of how the dead whale almost sank and what the Makah did to recover it—and the tension of the political consequences if they didn’t.

While Sullivan doesn’t dwell too much on big-picture whale politics, the book leaves little doubt that this whale hunt was, first and foremost, a political act— for individuals, tribes, whale hunters, governments, and environmentalists alike. While the Makah may have been reclaiming both treaty rights and ancient rites, the rest of us were pulled in and played a role in a much larger, symbolic event, an unfinished story about humans, nature, and identity that turned on an act of violence and its meaning.