In 1995, Patrick O’Brian made his first, last, and only visit to the Pacific Northwest. The O’Brian cult grows thick as kelp here, centering around his 20-volume series of novels about the Royal Navy of the Napoleonic era known as the Aubrey/ Maturin novels. They are just the thing to please seafaring readers and fans of Masterpiece Theater-style entertainments.

I interviewed Patrick O’Brian on stage for the Arts & Lectures series in both Seattle and Portland, and it was a difficult task: I was warned in advance by his US editor, Norton’s Starling Lawrence, that O’Brian disliked personal questions so much that they were likely to be met with frigid silence, so any of those audience-pleasing queries about the author’s background were off-limits. To top it off, the author had famously disparaged the whole interview process when one of his fictional characters, Dr. Stephen Maturin—a character most readers assume speaks for O’Brian himself—declared in the novel The Truelove, “Question and answer is not a civilized form of conversation.”

Patrick OBrian: A Life Revealed by Dean King Henry Holt & Co., $27.50

Caesar by Patrick OBrian W.W. Norton & Co., $21.95

Hussein by Patrick OBrian W.W. Norton & Co., $23.95

Devotees who may have expected a cuddly, mellow man of letters did not get one. He was more like one of the inhabitants of his books. He was thin with white hair and a sharp face, and insisted upon being called “Mr. O’Brian.” He was charming, smart, and prickly. He loved talking about his interests (natural history, Jane Austen, 18th-century British politics) and turned monosyllabic if a subject did not interest him. He seemed uncomfortable with the modern world, even slightly unfamiliar with it. I remember the shock on his face when he was offered a Seattle deli sandwich that could have fed four O’Brians. In Portland, I met him in the hotel lobby: Coming off the elevator, he saw a luggage dolly with an elaborate brass fixture on top. His eyes twinkled with delight, and he wondered aloud what the Marquis de Sade would have done with such a contraption.

He was an intensely private man, and he didn’t become famous until the last decade of his life, when sales of his “sea stories” took off and he began to receive mainstream recognition from critics. At 80, he had lived most of his adult life in relative obscurity in southern France. He had written some promising fiction in the early 1950s that had gained him a little notice; he had supported himself for years translating French authors such as Simone de Beauvoir into English. He had written a superb biography of Picasso, whom he knew. And he had written his sea novels, which slowly, quietly gained a following over the decades. In the early 1990s, the Washington Post dubbed him “the best writer you’ve never heard of.”

He claimed to be Irish and to have done intelligence work during World War II, but to his readers, he remained mostly a mystery: a highly skilled writer who came out of nowhere. He died in January at age 85.

Those who want to know more about O’Brian’s life can now read Dean King’s biography, Patrick O’Brian: A Life Revealed. O’Brian did not cooperate with this book and resisted King’s efforts to tell his full story. King dares to ask the impertinent questions others did not, and as a result makes an important contribution to understanding a writer’s complicated life. For what King reveals is that O’Brian had spent a good deal of his life trying to escape an earlier self and lying about his past.

It turns out O’Brian was something of a child prodigy of a writer, publishing his first novella, Caesar, at age 15 in 1930 and a full adventure novel, Hussein, at age 20 (both now back in print). He was not Irish but English, with a father of German descent. He grew up, sickly and unhappy, with eight siblings. His name was Richard Patrick Russ until he changed it after the war. He had two children by his first wife: a son, still alive, from whom he was estranged these last 40 years, and a daughter who died at age three from spina bifida. He abandoned his first family in poverty to marry Mary Tolstoy, an Englishwoman who was already married to a Russian count. In changing his name, O’Brian disowned his past; he cut off nearly all contact with his birth family and reinvented himself as a writer largely out of the public eye.

King’s book does a service in filling in these unknown facts of O’Brian’s life, unpleasant though some of them are. But he never successfully explains the whys of O’Brian’s reinventions and deceptions, nor does he fully and convincingly bring to life the remarkable, complicated, and engaging man whose magnum opus is regarded by some as one of the great literary achievements of this century.

Far from being a series of historical sea tales, the Aubrey/Maturin novels are fiction at its best, and their strength is what they reveal about human interactions. O’Brian was a master of great action stories in the tradition of C.S. Forester, yet with the depth of Joseph Conrad. But his real art had little to do with the sea or plotting. He understood and documented the most complex and intimate of relationships and interactions, capturing the sexiness of subtlety and tension. In books like Post Captain, he creates moments of potent inaction, in which nothing—yet everything—happens, with a skill rivaled by Austen or Henry James. King clearly appreciates O’Brian’s talent but offers little insight into how it evolved or gained such power.

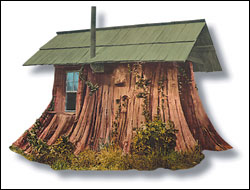

Though King interviewed many of O’Brian’s relatives, it is impossible to know what really happened in the household of his youth: Families are notoriously unreliable in describing their own failures. But that something excruciating happened is pretty clear, given O’Brian’s later annihilation of his birth family and his abandonment of his own. Clues abound in his newly reissued first book, Caesar, which is the story of a “panda-leopard,” a genetic hybrid of a snow leopard and a panda bear. While contemporary critics hailed the book as being written by a “boy Thoreau,” one reads it in the context of O’Brian’s life with horror. Children can be bloodthirsty, but O’Brian’s main character is a violent misfit who feeds on the flesh of others. His father is a dim memory and his mother is cruelly killed in the animal’s youth. The panda-leopard is later captured, and kept in a cage and tortured; it bonds with its keeper, but ultimately both die tragically. One could argue that Caesar is O’Brian’s autobiography of his childhood. The book is less a boy’s wildlife story than a map to a tortured subconscious.

Not long after O’Brian’s Seattle appearance, I asked him to recommend some books to read until the next installment of the Aubrey/Maturin series came out. Among those he recommended was Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son. Gosse was the Victorian era’s leading critic and his book was published anonymously in 1907. It is a searing portrait of Gosse’s childhood, a kind of highly literate Daddy Dearest that scandalized its age. Gosse describes it as a study (read “collision”) of two temperaments. I felt then that O’Brian had some identification with this book, and as I read King’s biography, I realized some of the parallels with his own life are uncanny. Both Gosse and O’Brian had fathers who were crackpot scientists. Gosse’s was a marine biologist who tried to reconcile the Bible and Darwin; O’Brian’s a physician who patented oddball inventions and attempted to treat venereal disease with electrolysis. Both grew up somewhat isolated; both spent many hours reading and educating themselves under the watchful eyes of dominating and self-righteous fathers; both lost their birth mothers at an early age; both bonded more closely with their stepmothers. Both left the paternal nest with a profound sense of alienation

O’Brian loved indirect communication. His books are full of it, as when battles are described after the fact or when readers learn via an overheard conversation that one of characters in the series has been killed off. I think O’Brian’s interest in Father and Son was more than literary: Like Caesar, it also holds clues about O’Brian’s own experiences and his development, and what later led him to remake his life entirely.

As a critic, Gosse reviewed Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians and noted that a central “agony” of Victorian life was its divided nature: Every eminent man had a public persona and a private life, which could be very different. The public was tidy and good; the private contained all the shadows. I think O’Brian lived by this code too, raised as he was by late Victorian parents. He attempted to maintain a divide between two selves, to keep the darkness from public view. It is evident from the richness of his works, however, that he did not suppress his demons, but wrestled with them until he had refined them into great literature. What else is there to know?