WHEN BAD-BOY ART CRITIC Dave Hickey gave a standing-room only lecture at UW’s Kane Hall last spring, he cracked the crowd up by saying, “I detect an alarming preponderance of earth tones. Do you even have art here? How could you see it?” Hickey explained that where he comes from—Las Vegas—a “giant orb” appears in the sky each day, “and it makes us strangely happy.”

What It Meant to be Modern: Seattle Art at Midcentury

Henry Art Gallery through January 23

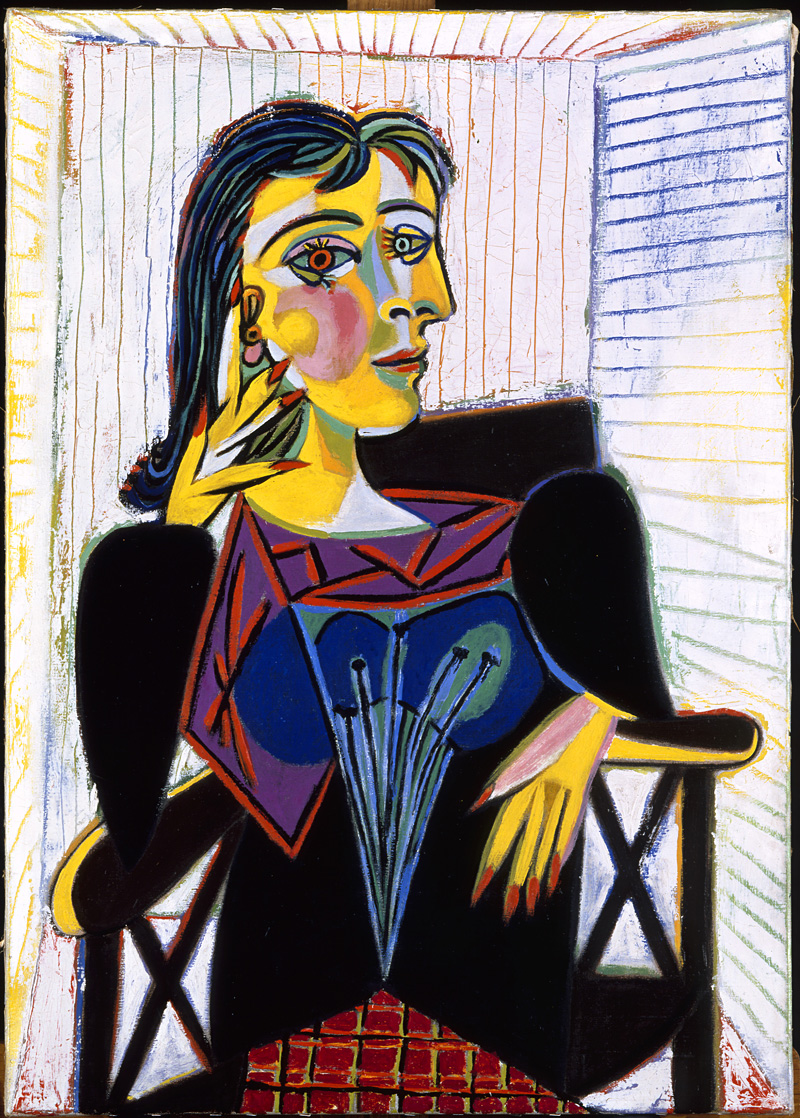

Earth tones do predominate in “What It Meant to be Modern,” the Henry’s wide-ranging show. Yet the somber palette also manages to make one “strangely happy.” Visiting the galleries is like stepping back to a time (1932-62) when Cubism met Northwest Coast Indian art beneath a persistent drizzle. In his new book on American art, Guggenheim curator Robert Rosenblum argues that from 1776 to the mid-20th century America produced no art that affected the course of Western painting—and when it finally did, “the first tremors of new life seem[ed] to have been found in the artistic periphery of the Northwest.” What it meant to be modern then was to believe that the world could be reinvented, that progress would result from the synthesis of ideas from Europe (and elsewhere) restated in American idioms. Not freighted with history but interested in connecting with it, the cliques among young Seattle’s institutions (UW, Cornish, the Henry) fomented a damp yet revolutionary climate. And in 1953 Life magazine first articulated the idea of a “Northwest School” in a now-famous article on Northwest artists.

Rosenblum traces the Northwest modern renaissance to one man: Mark Tobey. Of the 100 pieces currently on exhibit, Tobey’s have aged the best because they are the best; his 22 pieces in this show would constitute a must-see event on their own. English Still Life With Plaster Head (1933) is a modernist academic study. In Portrait of Ellen Hooker (1950), the female subject’s neck is elongated and her almond eyes are idealized: She is and isn’t of this world—she’s a creature of design, made into a shape, like a vase. Tobey’s fully in character here, with his key stylistic tic—that nervous little calligraphic line in the cross-hatching of her neck.

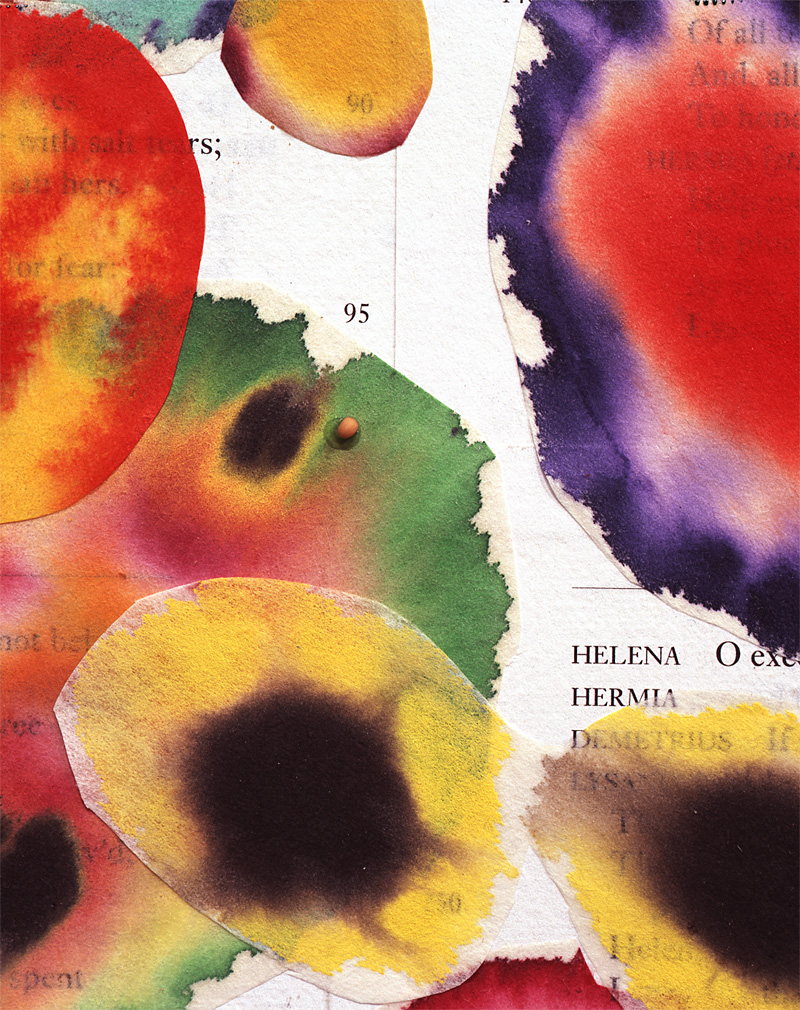

In Beach Space (1950), the abstract forms upstage the figure, leading to the net of little marks Tobey called “white writing” or “Hell under a lacy design.” His Festival (1953) gets even more abstract: A street scene, complete with streetlights, fades into a kinetic fog of similar marks. By the time he created the teeming strings of glue in the glorious La Resille (1961), Tobey had made the gradual shift from literal imagery toward the process of making art as a subject in itself.

The show’s influential works also include Paul Horiuchi’s intrepid leaps into abstraction, Alden Mason’s joyful, substantial Winter Message, Wendell Brazeau’s Legerlike (and eye-catchingly colorful) Still Life, La Tavola, and Morris Graves’ moody, primordial visions. Graves can be horrid, toxically sentimental, but if the Henry offered to give me a Tobey or Graves’ swirl and vortice-powered Sea, Fish and Constellation (1943), I might just take the Graves. Guy Anderson’s Deposition of a Miner (1952) transforms an injured miner, being lifted by his pals, into an Italian Renaissance Christ taken from the cross, complete with halo-like, geometric flecks of color. Helmi Juvonen may have heisted a line or two from that master of fancy, Paul Klee; his We Are the Seeds of Our Ancestors (1955) is a cartoonish take on evolution. A monkey by a river labeled “Puget Sound” gazes up at a perplexed man with a tail protruding from his red long johns and a Northwest Coast-style animal mask. The painting bears the legend, “I would rather be a monkey a-swingin’ in a tree than to be a well fed donkey in high society.”

Some of the best work on display isn’t necessarily the most famous. Margaret Tomkins, who had her own show at the Henry in 1962, uses brighter colors than Tobey in her By the Sea Sun (1955), but her layered washes and calligraphic line are worthy of comparison. And don’t overlook Walter Isaacs’ postcard-sized 1957 gouache Untitled—it packs the compositional punch of a Matisse.

The Henry show raises a poignant question: How come we can’t be modern anymore? Because the moment is over. Everybody knows about Cubism and Haida masks and sumi painting—gestures erupting from meditation. And nobody believes in the cult of the individual artist channeling the divine. It’s an ice age of irony out there, a deconstruction zone; even that’s gotten old. Progress? Don’t make us laugh. But when nobody’s looking, we can sneak off to this lost continent of modernism and be moved.