As you enter the exhibition, huge photos of Picasso greet you. His penetrating gaze seems to assert that he will perform miracles—beat nature at her own game. Built tough and squat like Houdini, he does indeed pull off the perilous feats of a magician. In 13 rooms, you see his relentless hunt for new ways to see, create, and evade the chains of convention and self-definition, only to come up with another trick, a new act of shape-shifting. By turns, he is harlequin, Minotaur, seducer, intellectual, and the world’s first international art star. For him, it’s all about transformation: “One starts a painting and then it becomes something quite else. It’s strange how little the artist’s wishes actually matter,” he said in the mid-1950s.

His first big trick: the battle against his own virtuosity. Beautifully evoked by the first two galleries, the somber blue period and the lyrical rose period (together spanning the first half-dozen years of the 1900s) clearly show Picasso as a master draftsman. Then in 1906, floored by a Paris exhibit of African masks and totems, he paints his Autoportrait. The crude, scrubbed, and manifestly manipulated image has no reference to traditional technique. It’s more as though he carves a form from paint, as he begins to fill his studio with his own primitivistic wooden figures. The portrait is a vastly simplified compilation of flattened shapes, with the cylinder neck you see in SAM’s great collection of African sculpture.

He obliterates yet more literalism in 1907 with studies for Les Demoiselles D’Avignon and with Bust of a Man, which transforms the nose of his 1906 self-portrait into a graphic right angle, one eye staring blank as an empty arch. The composition is fractured and faceted, with slashes of paint behind the face seeming to break away from the background.

Then, with Georges Braque, he pulled off his most magical trick: cubism. Line and form are forever cut loose from reference; a subject can be seen from many directions at once, and the picture plane plays paradoxically against illusionistic space. The layered vertices of Man with Mandolin (1911) charge the angular subject with eternal movement. The forms seem as though they will regenerate on their own, like a fugue playing forever.

As he pushed painting toward pure form, Picasso also challenged sculpture’s relentless materiality. In 1909’s Head of a Woman (Fernande), he cut into the surface of the face, making emptiness summon a shape, creating a matrix of edges that define it more as a form-in-motion.

He also used cubism’s formal advances to conjure the psychological—a nod to surrealism and the unconscious. In Bird, Head of a Woman (1929–30), two wired-together sieves are at once a head, a bird body, and a woman’s pregnant stomach. Two conical shapes protrude from the back of a mask, like African-sculpture breasts. On the other side, a face is apparent, with a curved bar in front, punctured with two cut-away eyeholes. It casts a dual shadow, like a grey painting on the white painted metal, a second set of eyes. The pursed mouth is also a small beak-like V-shape, a demure right angle. On the back, featherlike shapes extend like the tail of a bird, or hair in the wind. Long, slightly bent angles form an elongated neck or swaying bird legs. Each view of the sculpture is a different vision.

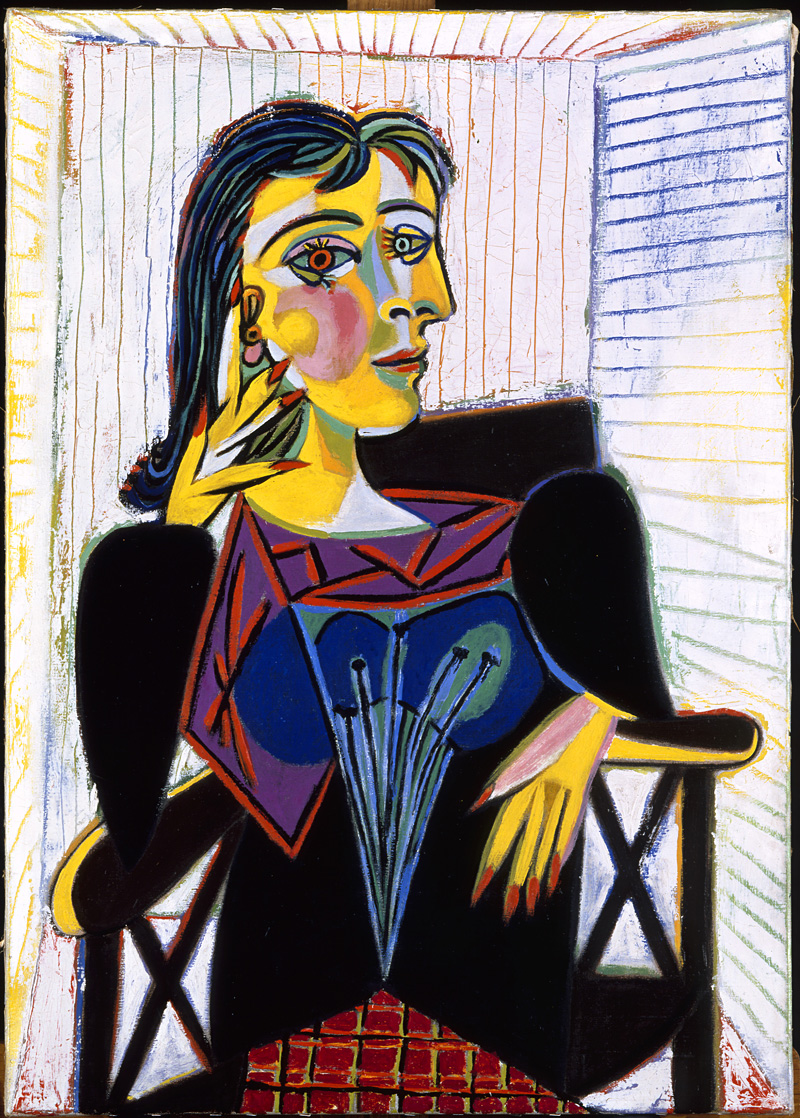

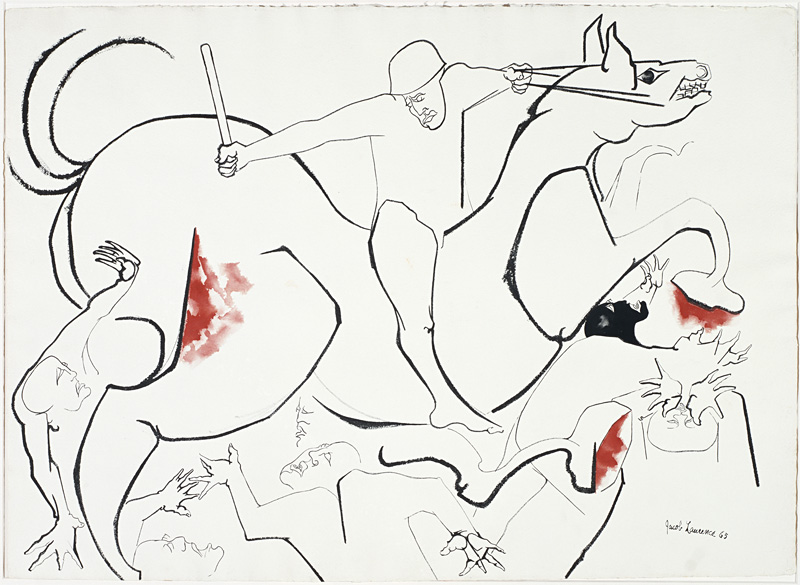

Notoriously, Picasso’s artistic transformations were triggered by each new (cruelly treated) love. In Figures at the Seashore (1931), his mistress Marie-Thérèse’s body is a landscape, a furniture-like object; the bronze Marie-Thérèse heads are monolithic. Cut to the next room, and new love Dora Maar: Her famous portraits are vivid, sharp, all lipstick and fingernails. (One from 1937 is shown here.) There is an intellectual brightness in her face, and a crackling emotionality. From there, you enter the grey-walled somber works of his World War II etchings, full of slain beasts, bull’s heads, and studies for Guernica.

Each room gives you a feel for the magician’s personal transformation. In a late painting, Picasso wears a tilted matador wig, brandishing swords and roguishly smoking a deserved cigar—a man of endless conquests celebrating his own creative machismo, the genius of a lifelong performance.