Even if you’ve never heard of Mark Musick, you’ve tasted his influence. In the late 1970s, he began supplying Robert Rosellini, owner of Rosellini’s Other Place, with an ever-changing blend of tiny, hand-picked baby lettuces, greens, and flowers from his communal farm in Arlington. The restaurant’s “impromptu salad” became one of the city’s culinary marvels. A few years later, Musick developed for Larry’s Markets the first commercially available version of what now gets shipped all over America as “spring mix.”

His greatest contributions to the Puget Sound food scene, however, are less tangible—and more valuable. In the food world, it’s easy to recognize the work of chefs and restaurant owners, people who create, invent, impress. But Musick is one of those who has patiently, earnestly—and to the general public, invisibly—knit together a sustainable-food community that has made our restaurants, markets, and food banks possible. “Mark has an amazing talent for recognizing and shepherding the forces, talent, and commitment of farmers and others who want to make the world a better and tastier place through honest agriculture,” says awards judge Jon Rowley.

Mark trained as a community organizer in the early 1970s, working with Navajo and Paiute Indians in the Southwest. When he returned to Washington, one of his earliest contributions to sustainable agriculture was helping to launch the Tilth Association. It emerged out of the 1974 Northwest Conference on Alternative Agriculture in Ellensburg, which Musick helped organize. Today, the regional Tilth movement in Oregon and Washington has grown into a diverse network of people devoted to organic farming and urban ecology. In its early years, Tilth was based at the collective Pragtree Farm, where Musick lived and worked. He helped publish Tilth’s quarterly journal and its first two books. “I decided that I would organize the information,” he says, “and let people organize themselves.”

Eventually, complications from childhood polio made farm work too physically demanding. In the mid-1980s Musick moved to Seattle, and later to a co-housing community on Vashon that he founded. But he hardly slowed down. As the farm program manager for the Pike Place Market from 1997 to 2002, he started the Market’s community-supported agriculture program as well as its Organic Wednesdays. More recently, he has been working with Seattle Public Utilities to divert good, edible food from the waste bins of restaurants and hotels into the city’s food banks.

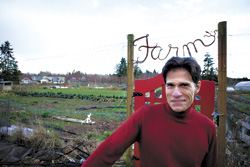

Musick, whose early studies in broadcast journalism are still evident in the precise diction of his speech and his anchorman’s good looks, is a relentless compiler of information who can file away, recover, and distribute every piece of data he collects. He writes articles on green business. He organizes forums. He forwards event notices and action alerts through the listserv of the Cascade Harvest Coalition, which links people engaged in sustaining local agriculture in Western Washington.

The personal, spiritual, and economic are intertwined for Musick. He seeks to build a network of people that he can rely on for practical as well as emotional support. Yet this network is so vast, and his way of life so modest, that it’s hard to see what he takes from the community for all that he gives to it.

The wonderful thing about food people like Musick, though, is that their ethics are grounded in a love of pleasure. Take his 60th birthday last year. Musick and his wife, Terry, spent a year putting together a massive dinner party to celebrate his life on Vashon. Every ingredient came from the island: Ham from a pig raised and slaughtered not far from their house. Dozens of vegetables from nearby gardens, every grower’s name logged in the couple’s planning book. To dress their salads, the Musicks hunted through neighbors’ backyards for the sourest grapes; to season the meal, a friend rowed out into the Sound and pulled up buckets of salt water they condensed into a brine. It was as much an art project as a political statement—and a party to boot.