It’s astounding how quickly we’ve all become accustomed to a daily onslaught of amateur photography. Not that long ago, only our family and closest friends ever glimpsed upon our own photographic efforts, and even then it was often greeted with somewhat of an internal eye-roll (the agonizing prospect of sitting through a vacation slideshow was literally a comedic trope). But the dawn of digital photography started to chip away at those norms, and the advent of camera phones and social media platforms knocked them to smithereens like a wrecking ball. Now poring over friends, family, and even strangers’ photos on Instagram or Facebook is an almost mindless time-killing routine. What’s fascinating about Polaroids: Personal, Private, Painterly at Bellevue Art Museum is how that modern acceptance does not seem to apply retroactively. In the physical medium, one can’t help but feel like an uneasy voyeur looking at others’ photos.

The exhibit’s Polaroids are culled from the collection of Seattleite Robert E. Jackson, one of the foremost collectors of mass photography. He’s amassed somewhere around 13,000 photos over a quarter century, and has shown parts of his collection at the National Gallery of Art, among other locales. For this latest presentation, Jackson worked with BAM curator Benedict Heywood to figure out a manageable slice to showcase. The result is around 150 Polaroids from the field of vernacular photography (aka photos with common, everyday life as the subject), more specifically amateur snapshots with no known author or identifiable subjects. These are photos not intended for the world at large to see, which taps into a key dynamic of the exhibit.

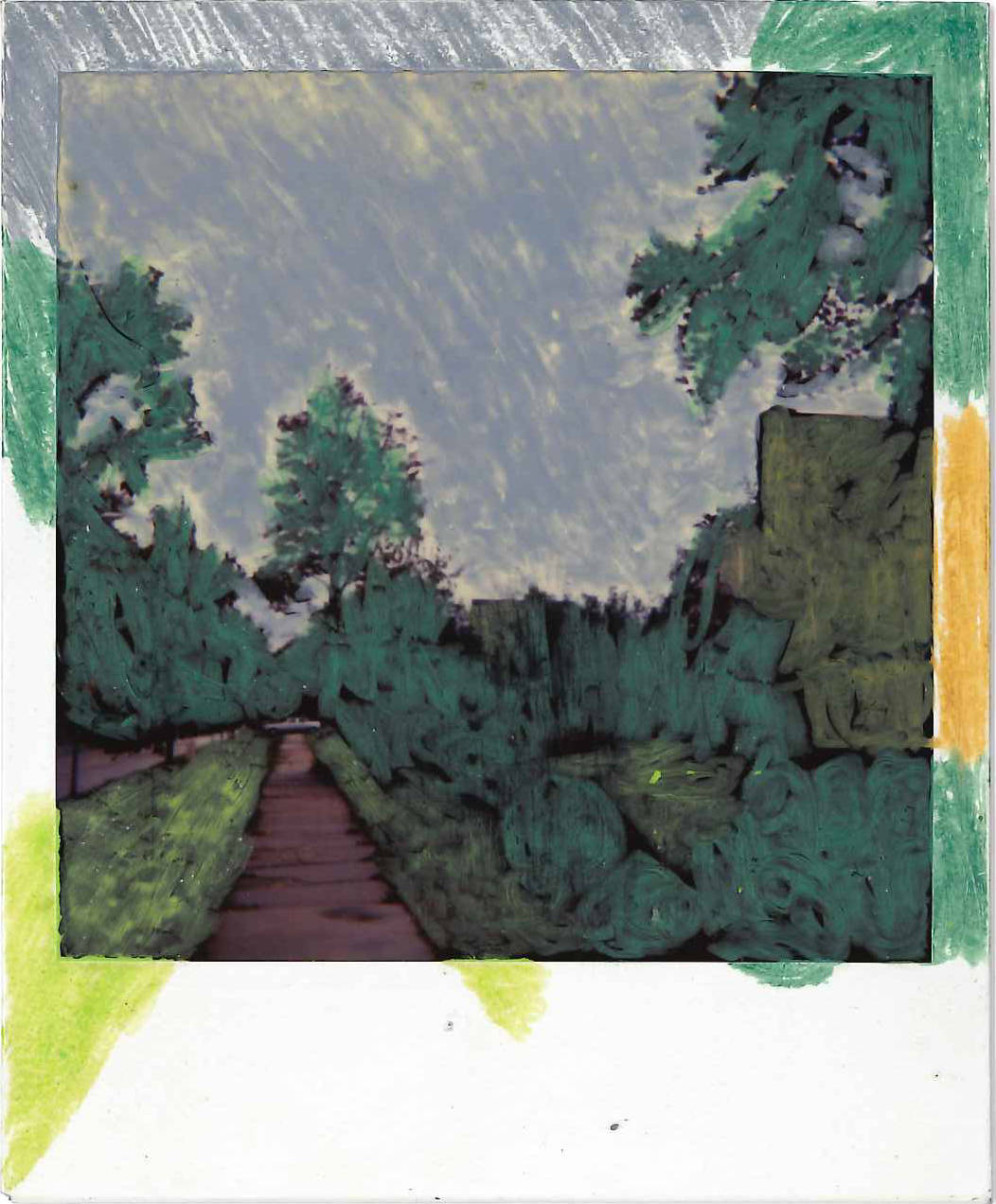

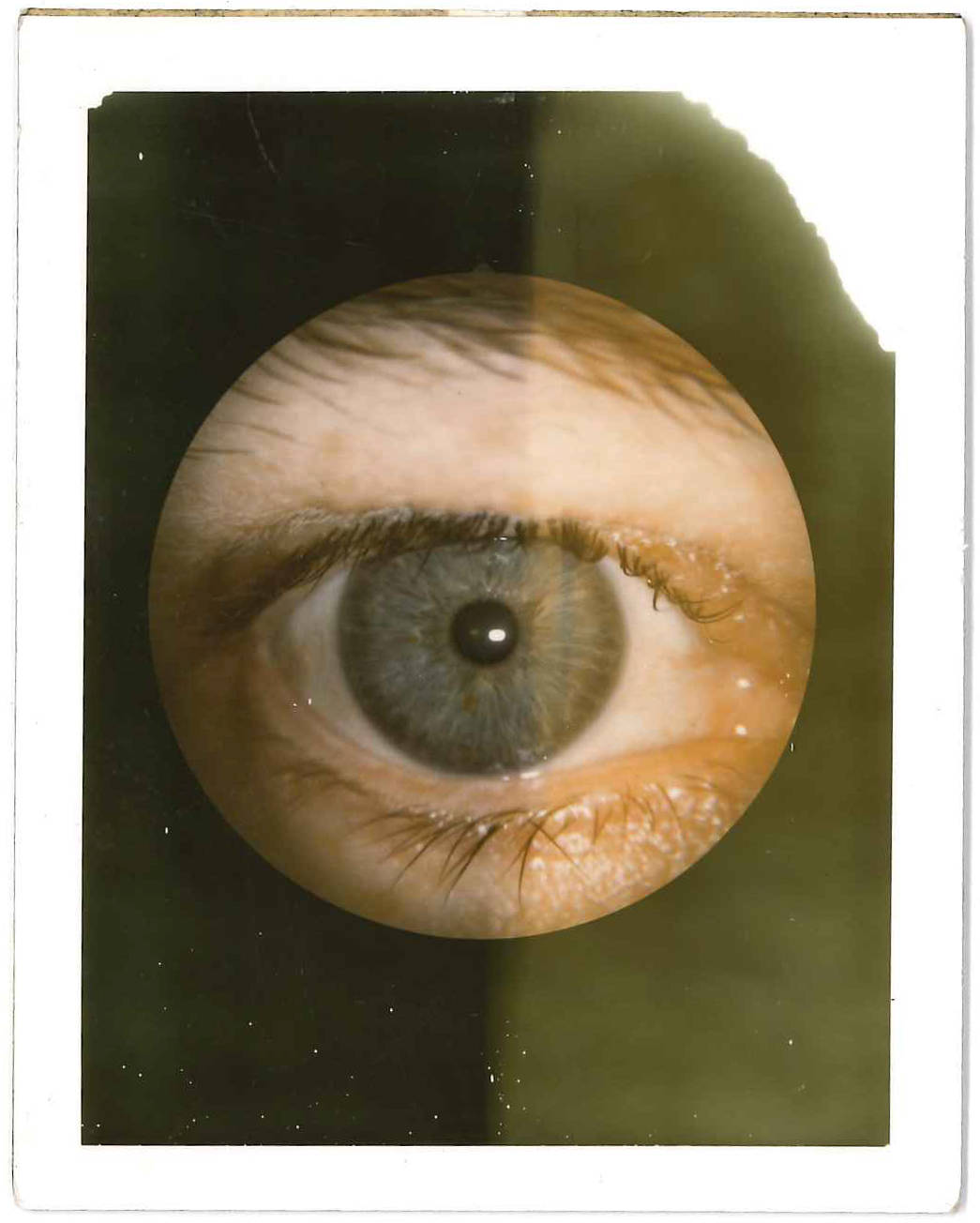

BAM loosely divides the exhibit into its three titular sections: personal, private, and painterly. Personal captures the most standard use of Polaroids — quickly capturing life moments that you can hold onto and possibly share with others: trips, daily happenings, and faces of loved ones. Private taps into a different Polaroid clientele, those snapped things that might not be “acceptable” to shoot on a roll of film, then send off to have someone else professionally develop it. Polaroid technology opened the door for more explicit, erotic, or not socially accepted moments to be immortalized: from crossdressing busts to the lick of a bloodied ankle (nothing too extreme is presented at BAM). Painterly focuses on artistic manipulation in the medium of Polaroids. These include manipulation through the shot via mirroring or rapid light movement and actually doing something to the printed Polaroid itself, like coloring over sections or making intentional cuts to the frame. The section also includes a handful of photos by Seattle artist Erik Simkins, who uses emulsion manipulation to turn Polaroid frames into something like formless abstract paintings. While interesting works on their own, they detract from the overall context of Jackson’s cobbled together collection; the same way that a modern impressionistic painting of Seattle landscape would seem out of place in an exhibit of French Impressionist landscapes.

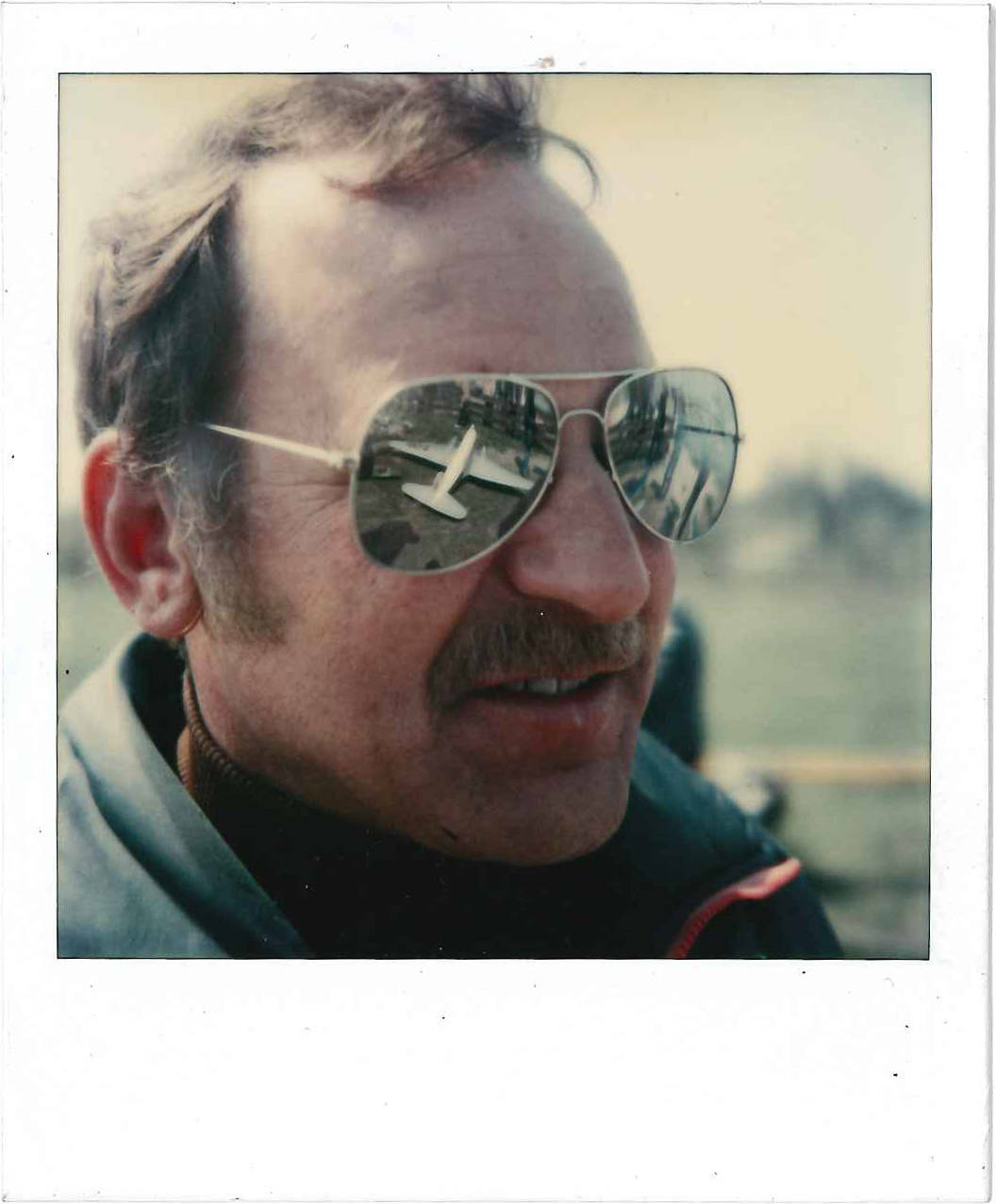

In addition to the diversity of subject matter, the Polaroids vary wildly both in terms of photographic skill. By the medium’s nature, most are amateurish in a way that captures an authenticity that’s still worthy of appreciation. There are a few shots that could stand alone as museum-worthy works. There’s a mustachioed man with a plane framed perfectly in one of the frames of his aviator sunglasses, a group of young black individuals at ease with an afro and shirtless muscles on full display, the eerie aura of a knife resting on the floor, a trio of women at the Statue of Liberty with a blimp flying overhead. Since the photos have no clear photographers, some are presented under the assumption they go together based on a common subject and composition (BAM also worked with Cory Verellen of Seattle Polaroid specialty shop Rare Medium to determine the type of film and rough date range of each shot). The most striking collection on display features 14 close-up, shadow-filled shots of the same woman acting out dramatic moods scrawled across the bottom of the frame ranging from “Flirting” to “Sad + Alone at the Bar” to “Noooooo!”

But Polaroids: Personal, Private, Painterly isn’t reliant on an individual frame blowing anyone away. It’s about the collective feeling of the presentation. It forces the viewer to confront their relationship with photography in a way that an exhibit by a professional artistic photographer never could. Even the lighthearted and comedic snaps in the collection carry an intimacy and immediacy via their physical form that just doesn’t exist in today’s world, and gazing at them makes you feel like you’re invading these photographers’ personal spaces. Even Polaroids were purposeful in an era before you could fire off dozens of shots via repeated taps on your phone screen. The ubiquitous always-on interconnectivity of our times has rewired our brains such that the once lauded instantaneous Polaroid now feels like a quaint relic of a slower time that we’re somehow violating by looking at strangers’ snapshots. It’s an artistic discomfort worth leaning into.

Polaroids: Personal, Private, Painterly

Through March 24 | Bellevue Arts Museum | $15 | bellevuearts.org