Reading

Martin Luther King Speech

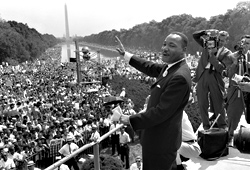

When King, just 35, was awarded the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, he responded not only by donating his $54,123 in prize money to further the civil rights cause but also with stirring oratory. Like his better-known March on Washington “I Have a Dream” speech the previous year, his Nobel acceptance speech (a celebration and justification of nonviolence) unfurls grandly as a litany of personal beliefs, gathering force with each repetition: “I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality. I refuse to accept the cynical notion that nation after nation must spiral down a militaristic stairway into the hell of thermonuclear destruction. . . . I believe that wounded justice, lying prostrate on the blood-flowing streets of our nations, can be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men. I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality, and freedom for their spirits. I believe that what self-centered men have torn down, men other-centered can build up.” To mark Martin Luther King Day, the Mirror Stage Company’s Suzanne M. Cohen stages a reading of the speech, surrounding a performance by actor Umémé with a multimedia presentation of still photos and recordings of voices of the period: King himself, JFK, LBJ, and Malcolm X. Center House, Seattle Center, www.seattle center.com. Free. 2 p.m. GAVIN BORCHERT

Books

Barbara Ehrenreich

Barbara Ehrenreich turns her attention to joy—deep, collective joy—and the way it is expressed. As the best-selling social commentator and cultural historian says in the introduction of Dancing in the Streets: “I explored the dark side of human collective excitement, as expressed in rites of human sacrifice and war. As I ventured into the less destructive kinds of festivities that concern us here, I recognized emotional themes I had encountered decades ago, at rock concerts, informal parties, and organized ‘happenings.'” She shows that mass festivities were met with fear—elites feared they would topple society’s hierarchies—and she shows how those fears were rightly placed, citing the French Revolution and uprisings in the New World. Yet outbreaks of group revelry persist, as Ehrenreich shows, pointing to the ’60s rock and roll rebellion and the more recent “carnivalization” of sports. She concludes that because we are innately social beings, we are impelled to share joy and therefore able to envision and even create a more peaceable future. “I suspect that many readers will have similar points of reference—whether religious or ‘recreational’—for the material in this book, and will be willing to ask with me: If we possess this capacity for collective ecstasy, why do we so seldom put it to use?” Presented by the Town Hall Center for Civic Life with Elliott Bay Book Co. Downstairs at Town Hall (enter on Seneca Street), 1119 Eighth Ave., 652-4255, www.townhallseattle.org. $5 at the door. 7:30 p.m. JOANNE GARRETT