Let’s be honest: A lot of people will go see August Wilson’s Radio Golf (through Saturday, Feb. 18; Seattle Repertory Theatre, 206-443-2222, www.seattlerep.org) out of a sense of duty, because they know it’s an Important Play. After his death last October, Wilson was roundly (and rightly) eulogized as an epic poet and visionary. And his lifelong project—chronicling the 20th-century African-American experience, decade by decade, in a series of 10 plays—is, by any measure, heroic.

But Rep regulars have not forgotten King Hedley II. That was the Wilson script we saw in its infancy in 2000 . . . a grim, untidy affair whose bolts of brilliance were not enough to energize its three-plus-hour running time. No one likes to say this, because Wilson at his best was a sort of prophet, the conscience of his generation. Wilson at his worst was windy and predictable, and really, no one could be expected to write 10 Fences.

No wonder some of us set our jaws before entering the theater last week, prepared to be uplifted and edified, but not necessarily entertained. We knew Radio Golf was Wilson’s final play; he was still revising when he died. So we were in danger of seeing a rambling rough draft that would, in fact, never be finished.

How nice to report, then, that Radio Golf is a quiet pleasure—full of sly humor and sharp observations on race and class. At two and a half hours, the production is leisurely, but not boring, and the five central performances are rich and well balanced. Director Kenny Leon and dramaturg Todd Kreidler, both of whom knew Wilson well, deserve credit for finding the shape and substance of the script without Wilson in the theater to guide them.

Yes, the play is talky. (But what talk! Wilson made music out of the voices of Pittsburgh’s Hill District.) Characters amble onto the set—a neighborhood redevelopment office in the district in the late 1990s—and hold long, looping conversations with whomever they find there, digressing into anecdotes about everything from chickens to bread pudding.

And yes, it’s predictable. Like The Piano Lesson and other Wilson dramas, it centers on a disputed piece of property—in this case, a house, which represents history (and, to get really pedantic, the legacy of slavery and race relations in America). Some characters want to enshrine that history, others want to cast it off. Most everyone wants to move forward, some by working within the system, others by circumventing it, and still others (and there’s a good joke about this revolutionary phrase in Radio Golf) “by any means necessary.”

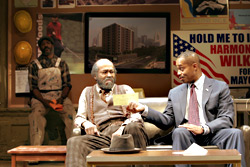

Almost all of Wilson’s plays follow a tragic arc; great plans hatched in Act 1 become the central characters’ undoing in Act 2. In Radio Golf, Harmond Wilks (Rocky Carroll) schemes to revitalize the Hill District and claim the mayorship of Pittsburgh to boot. Throughout the first act, Harmond and his cohorts claim “Everything is lining up so good for us” and “I feel so good about all this”; he and his best friend/business partner Roosevelt Hicks (James A. Williams) even sing a refrain of “Blue Skies” to each other. You think that luck, as the song goes, is going to come a-knockin’ at their door? If you do, you haven’t seen enough August Wilson plays.

And yet, even though the ending speed-dialed us from the first scene, I enjoyed spending time with these people: the honest, optimistic Harmond, the wise fool Elder Joseph Barlow (Anthony Chisholm), the low-down truth teller John Earl Jelks (Sterling Johnson). They made me think— and better, made me laugh, along with everyone around me. And to get an audience that is half black, half white (too rare at the Rep and at most Seattle theaters) laughing at the same things is no small accomplishment.

So, go because it’s Important. Or because it’s pleasurable. Or both. As Harmond finds out in Radio Golf, sometimes it’s surprisingly liberating to do the right thing.