Casting now: for lead in film treatment of Col. Matthew Bogdanos’ memoir of tracing precious artifacts stolen from the Iraqi National Museum during the invasion in 2003. Should be about 50 years of age, Greek-American, handsome, buff (terrific abs a plus), familiar with boxing, ballet, and traditional Greek tabletop dancing, believable quoting Kant, Nietzsche, and Browning while snapping off 135 push-ups; must be magnetic, a natural leader of men, and not more than 5-feet, 6-inches in stature.

That latter requirement may seem odd by Hollywood standards, but I’m sure the real-life Bogdanos would agree that nothing in his character makes sense without reference to his height. Bogdanos has been proving himself from childhood on, growing up in a large, poor, quarrelsome Greek family in Manhattan, earning honors degrees in classics from Bucknell and in law from Columbia. A Marine Corps officer since 1985, an assistant New York DA since 1988, Bogdanos is clearly a driven man, shuttling between assignments prosecuting Sean Combs and chasing insurgents in Afghanistan while siring several children and, Zelig-like, being on the spot for multiple encounters with history. (His lower Manhattan home was—and still is—four blocks from Ground Zero.) No wonder he quotes Homer on Hector and believes in fate. Even in his own offhand words, he’s almost too good to be believed. (He’s contributing his royalties to the Iraqi National Museum, for Pete’s sake!)

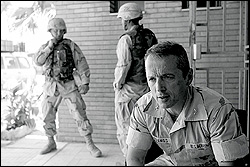

Between 9/11 and his brief return to civilian life after service in Afghanistan, Bogdanos was busy enough to provide material for a satisfying memoir, but that period is only a warm-up exercise for Thieves of Baghdad (Bloomsbury, $25.95), the bulk of which takes place in Iraq, in the dusty, devastated halls and storerooms of one of the world’s greatest collections of ancient Middle Eastern art, artifacts, and adornments created for the many kings and cultures occupying the plains of the Tigris and Euphrates between the fourth and first millennium B.C. The cast of characters is almost overfull with straight-arrow military types, FBI forensic experts, miscellaneous quasi-civilian hard guys, ingenuously evasive Iraqis, and an unknown number of shadowy baddies, motives and means unknown, but all ready to shoot without warning.

Thieves is a stylistic curiosity. It was co-written with William Patrick, whose best-known prior work was Blood Winter, an admired thriller set in 1915 Berlin. This book is clearly meant to be a page-turner, but keeps bogging down in endless paragraphs of technical minutiae: how an interdepartmental law-enforcement task force is organized, how to manage effective communications in a combat zone, just what the Akkadians did to the Sumerians in the Battle of Uruk, c. 2750 B.C. But paradoxically, it’s the bogged-down parts that lend the book its genuine fascination. Anybody can write a thriller; few are qualified by 30 years of personal and professional experience to guide readers through the world of professional military operations in a combat zone, while at the same time painting in 5,000 years of history as salient to the broad human condition as it is to today’s battlefields.

Best of all are the author’s asides about minute-by-minute life in the midst of violence and chaos. My favorite moment comes early, when Bogdanos heads up to the one spot on the roof of the museum where his cell phone works, lying down behind a parapet while making his calls to avoid being picked off by the omnipresent snipers. But there are hundreds more like it—little flashes of experience and insight that make a scene solidify into reality for the reader. Thieves is not “well written,” but it admits us to a world as only the greatest novelists, the Tolstoys and Flauberts, are able to do.

Producers and screenwriters are surely already tearing at one another’s throats in hopes of nabbing the movie rights to the book. I wish them luck finding someone to play Bogdanos. Even more tricky is the matter of a romantic interest. The colonel is, after all, married, with four children. There’s an obvious “love interest” right in the center of the story: Dr. Nawala al-Mutwali, the director of the National Museum, who works alongside Bogdanos from the moment of his arrival in Iraq. But I somehow don’t see Angelina Jolie being interested in playing a woman who’s never seen without her burqa, and whom the hero, when she faints, is forced to think twice about catching, because he knows she would prefer to crack her skull open on the concrete than have a man’s hands catch her.

Matthew Bogdanos will appear at University Book Store, 7 p.m. Thurs., Dec. 8.