This month’s program at Pacific Northwest Ballet was what bookers call a mixed bill (through Sun., Nov. 13; 206-441-2424 or www.pnb.org). Strictly speaking, that means only that the program features no single piece, choreographer, or theme. Practically speaking, it also usually means a mixed bag as well, juxtaposing pieces created in different dance eras for different companies with differing aesthetic goals, usually in different states of polish as regards casting and rehearsal.

Opening the evening Thursday was Concerto Barocco, one of George Balanchine’s earliest exercises in abstract classicism, created in 1941 and a mainstay of the PNB repertory since 1978. It was danced with a buttery smoothness by the eight-woman corps, which seemed to me a little off-key with the angular clarity of its Bach score, but maybe I’ve been listening to too many raspy early-instrument renditions of the music. Carrie Imler and Patricia Barker, respectively spunky and Olympian, seemed stylistically too different for the two lead female roles in the rapid-paced first and third movements, but Barker’s long, fluid line hit the mark in the long central arioso, with Stanko Milov as her discreetly adoring partner.

Second up was the pastoral Jardi Tancat, a novelty for me though a mainstay of the PNB rep since 1996. It was danced with great concentration by a talented cast of six and won cheers from the opening-night audience. However, for me there has always been something faintly comic about dance pieces portraying the earthy passions of simple people of the soil, and Nacho Duato’s composition, created in 1983 for an international company (Nederlands Dans Theater), all but reeks of folkloric condescension. Duato says he draws his inspiration from the sultry culture of his native southern Spain, but his movement looks like Martha Graham in one of her folksier moods: Andalusian Spring, anyone? Sung by composer Maria del Mar Bonet, the recorded score sounds impeccably ethnic. But in the absence of translations, one is tempted to make up scenarios of one’s own à la Robert Benchley: “Paquita is annoyed with Esteban because he does not care for her oatcakes. She throws herself down a well.”

In homage to George Frideric Handel on the occasion of his 300th birthday in 1985, former PNB artistic director Kent Stowell stitched together bits of operas, oratorios, and instrumental works from various periods of the Anglo-German genius’s 50-year composing career as reorchestrated and vulgarized by the late Eugene Ormandy. Twenty years later, Handel is lively as ever, and I suppose one could say the same of Hail to the Conquering Hero, if it had ever shown the slightest sign of life in the first place. Alas, it is and has always been as decoratively gutless as a stuffed owl in a vitrine.

The corps of 16 moons about decorously; Imler does her spunky turn in a brief hornpipe; Mara Vinson and Jonathan Porretta perform a pointless, passionless pas de deux as if they believe in what they are doing. Christophe Maraval tries to lend some weight and credibility to the principal male role, but since his steps are of no interest and he spends most of his time being helped to stand up by a bevy of concerned chorines, he comes off more like a victim than a hero. Why this piece, of all those Stowell created in his 30 years at PNB, is still in repertory is a mystery as deep as that of faith.

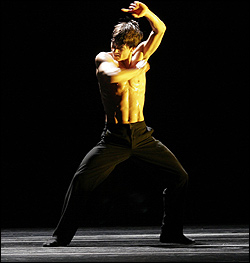

Hero looked particularly taxidermic because it followed on the evening’s one premiere, a 14-minute male solo created last year by German choreographer Marco Goecke. For a grizzled veteran of Eurodance, Mopey sounded highly suspect. Europe has so many subsidized ballet companies and so few distinguished ballet choreographers that the appearance of even potential talent can produce a press feeding frenzy; Goecke, with fewer than half a dozen works to his credit, has shot from obscurity to the post of house choreographer of the Hamburg Ballet in a matter of three years.

Maybe my relief at finding that Goecke is a choreograpaher, not a charlatan, leads me to overvalue Mopey, but I doubt it. Fourteen minutes is a long time to hold an audience’s attention even with a stageful of dancers; to keep us watching one man that long, in dim light and much of the time with his back to us, requires a real grasp of continuity: of gesture, pace, and concentration. The music turns out to be exquisitely appropriate: C.P.E. Bach’s impacted Sturm und Drang seems as contemporary as Goecke’s impacted, spasmodic movement. In James Moore’s dizzying execution, you can look at the piece as a portrait of a loner kid in midadolescent meltdown; to me, it is more like a look into the creative cauldron of a dancer discovering that he has something more to say than the moves that have been set on him by others. It’s exhilarating; it’s frightening; it’s funny. Is it art? Art can wait.