No one ever said making police accountability work in Seattle would be easy, and it hasn’t been. Legislated into life in 1999 as a way to bring some measure of public oversight to investigations of police misconduct, the Office of Professional Accountability (OPA) has been a civic sore spot ever since. The powerful Seattle Police Officers Guild and its member street cops don’t trust it to fairly investigate complaints of officer misconduct. Community watchdogs don’t think the OPA adequately handles citizen complaints against cops. Elected officials consider it a hot potato.

If that weren’t enough, a member of the OPA’s review board—three appointed citizens charged with overseeing the process—is threatening to resign because he feels muzzled. Meanwhile, Seattle Weekly has learned that OPA recently botched an investigation into allegations of excessive force involving Seattle police officers who arrested a homeless man, force so extreme that the man was left with life-threatening internal injuries.

When the OPA was conceived, in the wake of concerns about perceived shortcomings in police oversight, one of the most ticklish provisions was for the civilian review board to examine a random sample of OPA’s concluded investigations. OPA looks into internal complaints against police as well as citizen-generated complaints and reports to the City Council and the public on how well the system works. That mission sounded innocent enough at the outset—to everyone except police, whose union filed a lawsuit against the city over the review board’s role. The suit was settled by having board members sign a confidentiality agreement, prohibiting them from releasing identifying information about officers gleaned from already heavily redacted case files. Peter Holmes, an attorney on leave from Miller Nash, a downtown law firm, and Lynn Iglitzen, a former chair of the Seattle Human Rights Commission, are the current review board members. The third spot is unoccupied, awaiting nomination of another citizen by the City Council, which appoints review board members. Members receive a small monthly stipend for their work.

When Holmes and Iglitzen prepared their most recent report to the council in April, they had questions about whether it potentially violated the confidentiality agreement. Their report didn’t name officers—those identities are hidden even from review board members— but Holmes says they wanted to quote passages from OPA investigative reports to give the council and the public an accurate picture of what they were seeing. The worry for the board members was that even without names, the release of OPA information could be construed as somehow revealing an officer’s identity, opening them up to litigation by the union.

Holmes and Iglitzen sought a legal opinion from City Attorney Tom Carr’s office about whether their report breached the confidentiality agreement. But Carr refused to offer an opinion, even though his office does such assessments on a regular basis for city agencies. Carr’s spokesperson, Kathyrn Harper, offered “no comment” when Seattle Weekly recently asked for an explanation. The review board members also asked Mayor Greg Nickels’ office if it would indemnify them, as provided for in the confidentiality agreement. Nickels’ office refused.

The two released their report on April 30. They are still frustrated by how they were treated and, like some watchdogs in the community, wonder if they sense subtle censorship at work. “You’ve got citizen volunteers at peril, simply trying to do their job in good faith,” says Holmes. “You either have to have an opinion from the city attorney or city saying, ‘We are going to back you up.’ They totally sat back and said, ‘No.’ That makes it seem that you can’t disclose anything, and if you can’t disclose anything, then what in the world can you report on?”

Holmes says, as a result, he’s been thinking of resigning from the board, which would be a blow to the OPA’s credibility as an answer, in small measure, to civilian skepticism about police- misconduct investigations. Holmes says he’d advise any future board members not to sign the agreement. “I wish I’d never signed it myself,” he says.

Even Sam Pailca, the civilian lawyer who is in her second term as the OPA’s director, calls the situation “not healthy.”

Tellingly, in its report, the review board stated that, in some cases, it was left with “the impression that OPA had been predisposed to exonerate” officers.

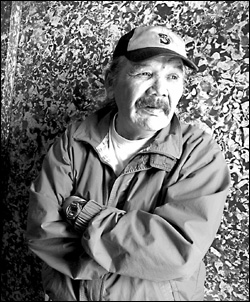

One case that would surely interest the civilian board members, were it to show up in their random sample of decisions to review, involves Raymond Nix, 66, who was arrested in front of a Belltown bar early last July 31 by a Seattle police anticrime team. Officers alleged in incident reports that they observed Nix making a suspected drug transaction with a woman outside the bar. During the arrest, Nix allegedly fought back and punched a Seattle police sergeant in the right eye. Officers pepper-sprayed Nix, applied a Taser to his stomach and buttocks, and slapped him across the face, according to Seattle police reports. Nix, the reports state, fought on. The sergeant, according to his report, admits to kicking Nix.

After he was subdued, Nix was taken to the King County Jail and then to Harborview Medical Center. He was diagnosed with a cracked rib and returned to jail. On Aug. 4, Nix passed out in a shower at the jail, where he was being held on charges of assault and possessing marijuana with intent to distribute. He was taken to Harborview again, where he was diagnosed with a ruptured spleen and a lacerated gut lining. His spleen was removed.

As he was wheeled out of surgery, Nix was greeted by Mary Ann Scott, an old friend who works at the Pike Place Market, where Nix hangs out. She was outraged at his treatment by police. On Aug. 15, she phoned in a complaint to OPA, alleging that officers had used excessive force on Nix and badly injured him. In April, Capt. Mark Evenson, who leads the OPA’s day-to-day work, sent Scott a letter. In it, Evenson stated that OPA had “administratively exonerated” the officers and there was no evidence of injuries to Nix.

A review of relevant OPA and SPD documents in the case, obtained as part of a motion in King County Superior Court by Nix’s attorney, Paul Richmond, make it clear, however, that someone at OPA did a poor job of investigating. The records also reveal troubling information about how officers documented the use of force on Nix. In their reports, officers describe Nix as a “large” man whose “brute strength” took them by surprise. Nix is 5-feet 10-inches and about 180 pounds. He is a senior citizen and moves slowly. At the time of his arrest, there was alcohol and cocaine in his system, according to medical records. Still, it’s difficult to think that he could ward off several police officers over the several minutes described in the reports, especially after being Tased. Stranger still, it is unclear when officers prepared those required use-of-force reports. OPA personnel first requested copies of the reports in August, according to records in the case. By mid-October, an e-mail from one of the involved officers says that the “packet” was missing and needed to be “re-created.” Use-of-force reports are supposed to be filed by officers as soon as possible after an incident, preferably by the close of that shift, says Pailca, the OPA’s civilian director.

In light of those inconsistencies and indications in SPD incident reports that Nix had been hospitalized, the OPA might have violated some of its procedures by not pursuing the case more actively. The office only tried to contact Nix—a homeless man—by mail and through his attorney. Pailca says that her investigators, each a sworn police officer, typically use more resourceful methods in tracking down witnesses and victims in an investigation, especially when homeless persons are involved. That wasn’t the case here.

In fact, OPA didn’t even contact Scott, the original complainant, after her initial call. She could have led them directly to Nix, since she sees him on a regular basis at the Market. To be fair, Richmond, Nix’s attorney, could have produced his client. But he says that he was having trouble obtaining documents in the criminal case against Nix and didn’t want to expose his client to any form of police questioning.

Still, obviously something worth clarifying happened when Nix was arrested, and OPA should have aggressively investigated the use of force, the odd reports, and Nix’s injuries. After inquiries by Nix’s attorney and Seattle Weekly, Pailca ordered the case reopened. She declined to answer questions about it, citing the ongoing investigation, which, like all of OPA’s cases, could result in criminal charges.

“Every use-of-force complaint is at the highest level of investigation,” Pailca says. As for the Nix case, she says, “We’ve got another chance, and we’ll take a very close look at it.”