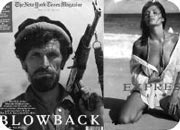

AFTER THE PLANES hit the towers, you couldn’t buy a New York Times in my neighborhood; even with some outlets getting the maximum triple allotment, they still sell out early. So I dug in the attic for one I saved seven years ago—the March 13, 1994, Times Magazine. Its cover, a foldout, shows in close-up a mujahedin warrior, Kalashnikov ready, staring with fixed fury into the Western lens. “The U.S. helps liberate Afghanistan,” the inscription reads. “Afghanistan becomes an outlaw nation, shipping heroin and terrorists abroad. The CIA has a word for this: BLOWBACK.”

What’s inside the fold made this cover seem even scarier then and makes it prescient now. A Guess jeans ad shows a luscious model who wears no jeans—a new Statue of Lubricity, as much an emblem of her land as the mujahedin was of his. She kneels on a tropical beach, eyes closed in some private ecstasy, unbuttoned shirt falling off her shoulders—smug and languid, as absorbed in the moment as her cover-mate is with battles to come. She represents everything he hates and is blissfully oblivious to the fact.

That was then; good-bye, blissful oblivion, hello, world. All of us—even a president whose foreign policy vision went no farther than Mexico—are getting a crash course in the other globalization: Hate, like capital, knows no borders. But still, in news shows, punditfests, and, especially, presidential speeches, the wide world, in all its North/South, rich/poor, secular/ theocratic complexity, is still seen mainly as the stage for an American drama. Some solipsism is understandable, considering the tragedy that’s just occurred in America. But our smug self-absorption and blindness to everyone else is also a main reason the rest of the world hates us.

Look at the rhetorical inflation that’s gone to whip up war spirit, and not just witless “crusade” talk. “War” itself is a dubious term in the circumstances. Wars are fought between nations; calling this “war” elevates criminals—fanatic and determined, but criminals nonetheless— to a status we don’t concede the Taliban. It gives bin Laden and his murderous dupes one more thing to celebrate. And it evokes a discouraging precedent: Two decades of the War on Drugs have yielded no end of waste, cruelty, and “collateral damage,” and no end to drugs.

Still, Bush’s writers wrote a stirring speech, and he delivered it well. But look at the reception it got: umpteen standing ovations from Congress, Demos included; Tom Daschle, who three weeks ago was set to kick the pins out from a failing presidency, hugging the commander-in-chief; the P-I and Times joining the editorial chorus and hailing Bush like Lincoln at Gettysburg. Some rallying round the flag is understandable, even necessary, and Bush has certainly found his poise after that initial skedaddle around the country. (Now they keep Cheney, who’s doing the real work, out of harm’s way.) All politics is local, and this “war” is political manna for the Statesman Formerly Known as Dubyah—not to mention for Gary (remember him?) Condit.

But as Britain’s Guardian notes, the Speech’s swaggering tones will play much worse in Karachi, Cairo, Istanbul, and Tashkent, where the campaign will be won or lost. And even with the “crusade” talk zipped, the official phraseology still rings as grandiose and bellicose. “Infinite Justice,” the moniker for the new campaign, strikes some Muslims (and, surely, Christians) as a blasphemous appropriation of divine justice. And the new “Office of Homeland Security” evokes the old Russian motherland, Nazi fatherland, and apartheid homelands. “Secure homelands?” Already the papers are calling it “home front security.” Wouldn’t “domestic security” have been good enough?

CRY OF THE PEOPLE

Every film critic and sundry other gasbags have weighed in as to which movie this real-life disaster most resembles. Nearly no one was cynical enough to mention Wag the Dog. And no one noticed the eerie resemblance to Broadcast News, about an air-headed TV anchor (anchor, president, what’s the difference?) whose charm raises him far above his ability. That character, played by William Hurt, becomes a star when he sheds a phony tear while conducting a poignant on-air interview. Bush’s turnaround, when he was transformed from deer in the headlights to fearless leader, came when he cried publicly for the victims in New York. In the post-Clintonian politics of feeling everyone’s pain, crying equals leadership. No doubt it also strikes fear into Taliban hearts.

FADE TO BLACK

Did you notice the progressive journalistic erasure of the image that’s haunted news shows and nightmares since Sept. 11? First the New York Times op-ed page showed the twin towers in blank outline. Then The New Yorker ran its ballyhooed cover with the towers almost imperceptibly silhouetted, black on black—a fitting end to a graphic long good-bye.