After we finished our bowls of fabada—a saffron-scented white-bean soup containing blood sausage, freshly ground chorizo, and cubes of braised pig trotters—one of the cooks stood up to announce the second course. “We’re going to have a Hector salad,” he said. “We sautéed up some Hector liver, and there’s some Hector bits, as well as confit pork that wasn’t from Hector, though he came from the same litter.”

Naming the pig we were about to eat sat ill with me, but I understood the impulse. Most of us about to dine on this animal had watched him die the day before.

At 9:30 on a cold, clear Sunday, I arrived at a Port Orchard farm and felt my ribs start to constrict. All week I’d been slipping the day’s excursion into conversation as nonchalantly as I could. What are you doing this weekend? Oh, going to a party on Saturday and a pig slaughter on Sunday. Most people, even vegetarians, expressed more interest than revulsion, but all of us treated my attendance as an unpleasant duty. No one asked if they could come along.

But I was attending the slaughter out of a sense of obligation as much as curiosity or appetite. Organizer Gabriel Claycamp was calling the event a “Sacrificio,” a re-creation of the Iberian tradition in which an entire village turns out to kill a pig and make sausages, hams, and other forms of preserved pork while feasting on more fresh cuts. (You can read about an authentic sacrificio in Anthony Bourdain’s A Cook’s Tour.) Slaughtering a pig for winter is still as common an experience in many parts of the world as attending a Super Bowl party is here.

Seattle has certainly seen animals killed for pig roasts, barbecues, and other private celebrations, and several local butchers do sell live animals for that purpose. Last February, underground-restaurant organizer Michael Hebberoy and Portland chef Morgan Brownlow invited a dozen Seattle chefs to a Vashon Island farm for a private master class in whole-hog slaughter and butchery. But Claycamp’s Sacrificio may have been the first combination slaughter, butchery class, and dinner held for the public. “First and foremost,” he said later, “I wanted people to walk away feeling like it was a respectful celebration, and that the animal was as far as possible from the polystyrene packages people pick up in the supermarkets.”

To me, attending the Sacrificio was part of my evolving relationship with meat. The fact that I, like many of my friends, talk about an “evolving relationship with meat” represents a cultural shift in itself. My parents both grew up in the country, killing chickens and rabbits for dinner. My dad worked in a butcher shop throughout high school, and our family (with the exception of my sister) never anthropomorphized animals or expressed distaste for meat. I think that as a society, though, we’re developing a schizoid approach to meat: As we grow more and more distanced from the realities of meat production, and as we long more and more for an emotional connection to it, we’ve inflated the killing of an animal for food, something that one or two generations back was simply a practical necessity, into a cathartic, therapy-requiring event. Especially in Seattle, especially after the publication of Michael Pollan’s Omnivore’s Dilemma, urban diners are feeling the need to be more “conscious” of where their food comes from. A host of food trends—the explosion of farmers markets, the incessant labeling of farms and artisanal producers on restaurant menus, the growing concerns about raising and killing domestic animals humanely, the ascendancy of pork, chefs’ recent love affair with offal—were all coming together in this one event.

My own relationship with meat shifted three or four years ago, when I promised myself that if I was going to eat it, I would do it as consciously as possible. That meant two rules. One: Accept the idea that I’m a predator eating the flesh of a dead animal. I eat, and enjoy, as many parts of the beast as I can stomach (including the stomach). I do not hide from reality by eating boneless, skinless, antiseptic chicken breast and justify my consumption as simply a means of adding “protein” to the meal. Two: Recognize that I eat more meat than my body needs and that meat doesn’t need to be central to every meal. When I’m off work, these days I only cook meat a few times a month, mostly for family members who love it more than I, and my daily meat consumption rarely exceeds 3 or 4 ounces.

Somehow, though, that wasn’t enough.

Claycamp is not a man to make a small gesture. The chef and cooking instructor, who showed up to the event coiffed in tiny, barrette-sculpted braids, is the guy behind underground restaurant Gypsy, famous for its 16-course dinner parties, page-long application for mailing-list supplicants, and spot on Bourdain’s Travel Channel show. (I reviewed Gypsy’s more casual, public sibling, Vagabond, in July 2007.) Above ground, he and wife Heidi run Culinary Communion, a six-year-old cooking school that teaches everything from how to boil water to how to break down a whole (dead) pig, and Claycamp’s most popular classes are his charcuterie series teaching the fundamentals of curing and smoking meats.

There were probably 20 people milling about the farm when I arrived, including a gaggle of 6- to 10-year-olds. Most of the people in attendance appeared to be Gypsy/Culinary Communion regulars who swapped stories of feasts and trips to New York, contributing to the event’s vibe of a big work-party barbecue.

Claycamp, the farmer, and a handful of volunteers were setting up the cooking tents and waiting for the Washington State Department of Agriculture–licensed mobile slaughter unit to arrive. I wandered down to the pen. A couple of wide-eyed goats were meandering around the small crowd, nibbling at zippers and camera cases. And there, in a chain-link-enclosed square of grass, rooting in the ground and snorting like a giant pug with sinusitis, was Hector. All 350 pounds of him.

While we waited for the butcher, who was about an hour late, I alternated between studying Hector and listening to Claycamp talk about his plans for the pig. We were going to turn Hector into two prosciutti—which would then hang for two years before being ready—as well as pounds and pounds of French-style saucisson sec and Spanish chorizo. The chef also had plans for the liver, ears, lard, loins, trotters, blood, and the rest—which he would cook up in a special meal for us the next night.

Most of us were making chitchat by asking each other why we decided to come or whether we were nervous. No one admitted to being wracked with dread, though anyone likely to be would probably have stayed home. I asked one of the fathers how he prepared his kids for the death. “Oh, they were excited about it,” he said. “I don’t know how they’ll actually respond when the pig is killed, but when we told them we’d be eating lunch at the farm but it probably wouldn’t be Hector, they got upset.”

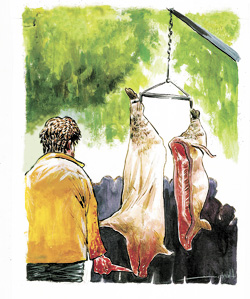

Farmer Joe’s mobile butchery unit—a large truck with a hoist in the back—finally arrived, and backed into place as 40 of us gathered around the pen. Claycamp came down to meet the pig dressed in waders and a yellow raincoat. The butcher, clad in a rubber apron with a metal knife holder hooked onto his belt, guided the winch hook into the pen.

I listened in while another man told his 6-year-old what was going to happen. “First Gabe is going to shoot the pig in the forehead,” he explained calmly, as the boy watched Hector snuffling. “That will stun it, but it’s not going to kill the pig because they need his heart to still be pumping to get out all the blood. Then they’re going to be hoisting the pig up, and the butcher is going to slit his throat. He’s going to be thrashing some, and all the blood is going to drain out of his throat. That’s what will kill him.” I experienced a small wave of discomfort watching Hector lift his head to sniff at the hook, and noticed for the first time that pigs have eyelashes.

Finally, everything was in place, and Claycamp spoke to the crowd. “We want to give thanks for the life and demise of Hector,” he said, then turned to the pig and thanked him personally. By now the pig was clearly nervous, though we weren’t sure if he knew of his death or was simply feeling the tension of the crowd. His flanks were twitching, his heart was beating harder. Some part of me wanted to go up to the animal and put my hand out to comfort him, but that seemed disingenuous, to say the least. I wasn’t his friend. I was his killer.

Claycamp, his eyes brilliant with adrenaline, picked up the rifle and moved into position. The farmers dumped some choice slop—melted ice cream and hamburger buns—into the pen as a final meal to reassure Hector. The crowd closed in, tense and curious. The rest happened so quickly I didn’t have time to react. As I was moving to get into better view, there was a crack, and when I saw Hector, a small red hole had appeared in the center of his forehead. He flopped down and began to twitch. The farmer’s crew quickly looped a chain around one hoof and hoisted the pig up, and the butcher darted in with a knife and stabbed deep into the pig’s neck. Blood began pumping out, and the unchained leg bicycled hard, pumping out the blood, clipping Claycamp in the ear hard enough to draw blood. The pig’s tongue was flickering in and out of his mouth as bright-red blood coursed past it. Claycamp’s apprentice was trying to catch as much as he could in two buckets, whisking kosher salt into the blood to keep it from coagulating.

It lasted less than two minutes. A perfect shot, a perfect cut, a clean death, with no screaming or squealing. In fact, the death felt remarkably anticlimactic: The pig was alive. Then the pig was dead. None of us moved, not even the kids, until the butcher gave the signal to hoist Hector’s dead carcass over the fence.

“That’ll do, pig. That’ll do,” Claycamp said. My eyes rolled.

It took another hour to clean the carcass by burning off the hair with a flame thrower and scrubbing off the outer layer of scorched skin. The only time I got skeeved out was when the butcher used a meat hook to pry off the pig’s toenails. Otherwise, the process seemed familiar to me as the animal got closer to the big cuts of meat I’ve broken down in the kitchen. When the body was clean, the butcher cut around the tail, then gently, as if slicing through marshmallows, slit the belly, catching the intestines as they bubbled out from the cut. The offal filled up a plastic dish tub. There was no smell.

He plucked out the rest of the organs—each unbloodied and beautiful—and revved up a chain saw to saw the body in two. Without even washing it, the cavity was clean and pale pink. When one of the children saw the brainpan and the rows of teeth in the separated halves, he let out a loud “Ewwwww,” which the other kids echoed. We all laughed, a tension breaker. It was the first and last time anyone expressed disgust.

After that, the slaughter turned into a cooking class and party. Another 20 to 30 people showed up, including a bluegrass band. Some of the participants prepared lunch, while the rest of us watched Claycamp lecture on how to break down a pig. The chef’s color had gone from excitement-flushed pink through post-slaughter pale green and had finally returned to human. He moved into teacher mode, describing cuts and muscle groups, remarking how different it felt to be working on a just-killed, gently steaming animal as he cut into it. Like most of us there, he had never seen or cut into flesh that had not gone through rigor mortis, the stiffening of the muscles that occurs soon after death. The food-processing literature refers to rigor mortis as “muscle conversion to meat,” and even the charcuterie-cookbook authors Claycamp had consulted in the weeks before the event said they’d never worked with pre-rigor pork.

We’d been asked to bring our knives and to sign a release form, taking responsibility for any cuts we should incur, and a third of us picked up our cutlery and volunteered to help out. Others mixed spices for the cures, helped tenderize the hams by pounding on them, or just hung out, eating and drinking wine. I took a turn cutting up the meat, and it did feel different: At body temperature, the fat was still translucent and gelatinous, not hard, and the flesh still had its jiggle. The carcass was harder to cut up, but not unpleasant, smelling mostly of singed hair with a little barnyard underneath. Someone cooked up the tenderloin and passed it around, and the meat tasted wonderful—almost beefy—but I didn’t enjoy how the pork looked well done but felt raw between my teeth.

As we munched on our pulled-pork sandwiches—not from the same pig, of course—it seemed to me that eating this next to the carcass of a pig we’d just killed, and only a few hundred feet from his mother, was a little obscene.

The friend I shared my thought with disagreed. “I think eating pork but refusing to see the pig die would be truly obscene,” she replied.

I partially agree. To me, the event had all the ceremony of a ritual. We were all there not to help kill an animal but to witness its death, to test our own resolve, to reify our ethics, to fill a void in our consciousness about one of the most mundane, but unacknowledged, aspects of our lives. “That’s why we called it ‘Sacrificio’ rather than ‘Slaughter,'” the chef told me later. “‘Slaughter’ is something that someone else does. Here we were all culpable. No one could wash their hands.”

The Sacrificio made me think of the scapegoat, a symbol much discussed by 19th-century and early-20th-century writers on religion who saw the “primitive” act of animal sacrifice as presaging the ultimate sacrifice at the core of Christian belief. But in our ritual, the symbolism was inverted. Instead of projecting our sins onto the sacrificial animal and ridding ourselves of them through its slaughter, we made the animal’s killer our scapegoat. We, the community of urban meat eaters, were projecting all of our doubts and insecurities about killing animals for food—our sins of participating in factory farming, our guilt over not being able to claim the moral purity so many vegetarians trumpet—onto Claycamp, who was absorbing them for our sakes and becoming the ultimate sinner.

But if the act absolved me, I couldn’t sense it. Perhaps, because of the death I witnessed, my relationship to meat may someday evolve again, but for the moment, nothing has changed. Of course, this was the cleanest death possible. Participating in a humane death of a humanely raised animal was like taking the state-sponsored tour of North Korea and reporting back that everyone looked happy. Having seen Hector die doesn’t stop my discomfort with factory farming from growing, nor my resolve to find ways to opt out whenever I can. But I’m also not going to eat, or enjoy, meat any less.

In fact, the next day, as we were tucking into our roasted Hector loin with romesco sauce, prunes, and figs, the table conversation segued into how we felt as if we’d made our peace with the slaughter long before the rifle shot. I mentioned to the woman sitting next to me, “I keep forgetting that I’m eating a pig I watched being slaughtered. I thought I should be feeling a more personal connection to this piece of pork, but it’s just a good meal.” She laughed.

But when we bit into our mincemeat pie with a flaky lard crust, the woman suddenly exclaimed, “Now I’m feeling a personal connection to Hector.” She sounded choked up.

I turned, concerned. “How so?”

She moaned. “Mmmmmmmmmmm.”

Note: This story has been changed to correct the spelling of Mr. Claycamp’s name.