Did the Seattle Monorail Project (SMP) let Paul Allen’s development company choose the monorail’s course through Seattle Center?

Conspiracy theorists have speculated for weeks that Allen’s Vulcan Northwest, owner of Experience Music Project as well as extensive real-estate holdings throughout Seattle, had a heavy hand in crafting the SMP’s new and greatly altered “preferred alternative” through Seattle Center. Documents released by the SMP last week reveal that, far from being paranoid, the conspiracy theorists may have been right all along.

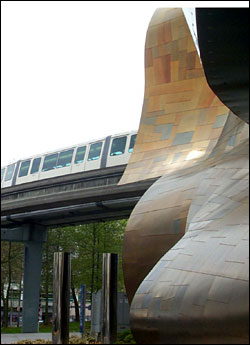

Consider: Less than a year ago, the SMP’s predecessor agency, the Elevated Transportation Company (ETC), released a “most promising alignment” that went around Seattle Center, had one stop in the Center’s vicinity, andmost troubling to Vulcancircumvented EMP, leaving an unsightly and very expensive hole through the fancifully engineered rock museum. After Vulcan and EMP representatives met with Mayor Greg Nickels and monorail agency staffers to discuss their concerns, the route was changed. In every instance, the changes accommodated Vulcan’s requests.

SMP board chairman Tom Weeks says the changes were made in response to a variety of constituencies, including the Downtown Seattle Association, Queen Anne-area residents, and EMP. “The constituent groups were pretty deeply divided,” Weeks says.

Allen’s influence should not be understated, however: Vulcan donated $30,000 to the monorail campaign; its lobbyists have long enjoyed a close relationship with monorail planners, meeting occasionally with monorail agency brass starting back in 2001. But things really started to pick up after the November 2002 election, when it became clear that Vulcan’s interests would best be served by, among other things, a route across Seattle Centerand through EMP.

Back in June, right after the “most promising” alignment was released, ETC consultant Bob Griebenow provided information to Vulcan lobbyist Jim Mueller and then-ETC staffer Joel Horn (now executive director of the Seattle Monorail Project) detailing the difference in costs between the preferred “Mercer alignment” north of the Center and a controversial cross-Center “Thomas route,” apparently in response to a request from Mueller and Horn. (The Thomas route was later replaced with the “northwestern route” currently on the table.) Griebenow’s numbers, predictably, favored the cross-Center option, showing that the Mercer route would be 1,610 feet longer, take 0.4 minutes longer, and cost $8 million more to build.

In January, after voters approved a plan that left the route around Seattle Center undecided, Vulcan’s vice president in charge of real estate, Ada Healey, wrote a seething letter to the monorail agency imploring monorail planners to go through, not around, Seattle Center. Healey did not mince words: Experience Music Project, she wrote, is “perhaps [the] most unique and special” aspect of the built environment at Seattle Center. “Great time, expense, and creativity were expended to design EMP around the existing monorail. It would be a travesty to tear the monorail out of EMP and leave a gaping hole in the building.”

IN ADDITION TO a cross-Center route, Vulcan asked for several specific changes. First, Seattle Center should get two stations, not just one near KeyArena. (Weeks notes that there were many arguments for adding a station, including higher ridership.) Second, after passing through EMP, the monorail should go to a new station at Fifth and Stewart, rather than stopping at Lenora, as was originally planned. The Downtown Seattle Association also argued for the Stewart Street stop. The Stewart station, Healey wrote, should include a skybridgecomplete with moving sidewalkslinking it to Westlake Center, an “emerging . . . transit hub” for buses, light rail, andsurprisethe proposed streetcar to South Lake Union, where Vulcan has extensive property holdings and ambitious development plans.

One month later, the monorail agency released its plan. Every one of the changes Vulcan requested had been made.

After the “preferred alternative” was released, the SMP did hold a series of public meetings to brief the public on its favored plan. The meetings wrapped up in just three days. Many people wondered why they weren’t given more time to comment on a plan that would send the monorail coursing through what many considered the heart of the Center.

Representatives of both One Reel, which produces Bumbershoot, and Folklife, two huge arts festivals that take place at the Center, have expressed dismay at the preferred alignment, which would send trains whizzing over audiences at four-to-12-minute intervals and would cut substantially into the open space that event planners need to stage large shows.

Fortunately, the one entity with the power to change the planthe Seattle City Councilhas seemed less than eager to jump aboard the agency’s preferred alignment, at least not without more discussion about the other alternatives. “They’d have to really demonstrate that this is going to work. My default position is that I don’t think this is a good idea,” council member Richard Conlin says. Even monorail fan Nick Licata is skeptical. “The burden of proof is definitely on the monorail authority to show how it would be an added benefit,” he says. In late March, City Council President Peter Steinbrueck, joined by Conlin and Licata, asked the agency to consider a fourth route south of the Center along Denny Way, which was rejected during early studies. The SMP said it would consider the Denny route along with the other alternatives.

It remains to be seen, however, whether the council members’ preference will stand a chance against the mayor and Vulcan’s lobbyists.