On a warm Thursday afternoon, soon-to-be 25-year-old Alicia Ortiz parks her silver hybrid Ford Escape outside the Seattle Weekly offices. She’s waiting for me. A University of Washington grad who works in liquor marketing and lives in Lower Queen Anne, Ortiz says she’s been driving for Sidecar since February. She was one of the early adopters.

Looking for extra money to pay for a trip to Rio, Ortiz says she signed up as a driver and interviewed with Sidecar on her smartphone, recording answers to prerecorded questions and sending them via the magic of modern technology to the company’s San Francisco headquarters—along with her driver’s-license number and photographic proof of her personal car insurance. After the company ran a criminal background check and she answered a few questions, Ortiz was all but official.

Next came a 90-minute “Sidecar U” class explaining the basics of the upstart ride-share business. Sidecar staff detailed how the company’s smartphone app connects local riders with local drivers and how the “suggested donation” payment system works, and offered a few pointers on how Ortiz could get the most action from the company’s growing community of riders. A quick ride-along with a member of Sidecar’s local staff sealed the deal.

For six months, Ortiz has been turning her car into modest profit, driving a handful of nights when her schedule allows, likening the income to the cash she earned babysitting in college. Over a recent four nights of driving, she says, she pocketed roughly $140.

“Sidecar is a really cool, easy way to make a little bit of extra money without even really noticing it,” she tells me. “I can always go online and do a couple rides.”

Ortiz doesn’t look like someone who’s fretting, but she is a player—though a minor one—in a major confrontation looming between the city and ride-share companies. Over the last year, Sidecar, Lyft, and UberX—products of tech-savvy, deep-pocketed Californians bent on disruption—have prompted an uproar from the taxi industry. Those complaints have led to the commission of a $100,000 study by the City of Seattle to determine whether ride shares are legal, or if these companies are sidestepping regulation to steal fares from taxis. If the study favors the latter, Ortiz and her ilk could be on the outs.

For now, Ortiz is enjoying the ride. She accepts her first ride request—who turns out to be a blonde Amazon employee on his way to the Showbox at the Market for a TechCrunch event—and she starts telling me about the appeal of Sidecar.

“It’s a community. There’s not going to be drivers if there’s not riders. And there’s not going to be any riders if there’s nobody there to pick them up. So the idea is we’re supporting one another,” Ortiz says. “If we really want to use resources that already exist and support ideas that make sense, I think ride-share and Sidecar should work.”

Sidecar hit Seattle first, in late 2012, quickly followed by Lyft and UberX in April. While there are differences among the three San Francisco–based companies—most notably with UberX, which requires payment up front and charges a rate in line with taxis—all three operate similarly: Everyday drivers across the city offer open seats in their personal cars in the name of sustainability, community, and progressive entrepreneurialism. In the case of Sidecar and Lyft, the driver’s carrot comes in the promise of a “suggested donation”—calculated by the app using distance traveled and mapping software—with riders free to pay whatever they see fit. Both companies say they then take 20 percent off the top of that donation, the rest going to the driver.

In practice, however, it can get slightly more complicated. As a Seattle Times story noted in June, Lyft has also hired drivers at $18 an hour. Exactly how many is unclear; the company says it’s a practice it employs when entering a market to make sure there are enough cars at the ready. While the Times piece makes this sound like the norm (it includes a profile of 50-year-old Lyft driver Sylvester Bush, who drove to Seattle every day from Renton to earn his $18 an hour), Lyft spokesperson Erin Simpson says that currently only 50 percent of Seattle Lyft drivers are working at this wage. As supply balances demand, eventually, she says, that number will reach zero.

UberX, meanwhile, is a spinoff of Uber (sometimes called Uber Black). The latter company entered Seattle in 2011, deploying only drivers with for-hire or chauffeur licenses, and carrying $1.05 million in insurance backing. The priciest of the new transportation options, Uber deploys a fleet of town cars and luxury SUVs, while the cheaper UberX focuses on hybrids. Some UberX drivers do have for-hire or chauffeur licenses, but it’s not required. UberX says it has a $2 million insurance policy covering drivers and passengers; Lyft and Sidecar both tout $1 million policies.

All three companies say they’re finding success in Seattle, a city where many consumers seem to be tired of taxi business as usual. The Times, on the other hand, has at least twice deemed the new ride shares illegal—a contention Lyft and Sidecar deny, and one city officials currently do their best to avoid commenting on.

“UberX should be the standard,” says nightlife entrepreneur Dave Meinert, who hasn’t been shy about letting city officials know where he stands. “The government-created cab monopoly has led to a lack of innovation and a bad product. Killing the competition won’t fix that.”

Citing competitive reasons, Lyft and Sidecar won’t say exactly how many drivers they have in the Seattle area; both claim more than a hundred. So does UberX.

Among Sidecar drivers, Ortiz seems to be a poster child. “Community definitely is a big piece of what we’re doing and what we’re trying to do,” says Sidecar co-founder Sunil Paul, striking many of the same notes as Ortiz. “We think it’s possible to rethink transportation into something that builds a new way of moving around that’s so convenient, so affordable, and so fun that it doesn’t compete with taxis, it competes with owning a car. . . . The idea is building around people, not around cars. That’s why community is a big part of it.”

Salah Mohamed is number 388. His Yellow Cab taxi-license number is painted on the front, back and side of the 2010 Prius where he says he spends 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Taxi drivers come in two forms: those who own their licenses and vehicles, and those who lease them. Mohamed is an owner/operator. Like all cabbies, he’s an independent contractor, relying on Yellow Cab for dispatch services but essentially on his own to make ends meet.

Licensed to work SeaTac Airport, throughout King County, and in Seattle, Mohamed has the most lucrative setup an operator/owner can have, which helps to support his family of four. He secured this envied position by paying for it: He’s on the hook every year for his city license and county license, and says he forks over $306 every week to the Port of Seattle to work the airport—all this on top of insurance costs, fuel, and maintenance. It’s an investment many like him have made, and one even more would-be license owners wish they could make.

Lately, however, Mohamed says the business isn’t what it used to be. Like a growing number of cab drivers, he feels pinched and disrespected by a system that’s supposed to protect him—a system, he notes, that employs thousands of cabbies throughout the county, and that gets a lot of his money. It’s also one the county’s nearly $5.9-billion-a-year tourism industry relies on. The local taxi industry is estimated to be a $97 million operation, delivering 5.2 million metered rides in Seattle alone in 2012 while supporting countless families.

But drivers like Mohamed say they’re struggling. The competing flat-rate, for-hire drivers and an allegedly unresponsive city have received the bulk of the blame in recent years. It’s onto this contentious landscape that upstart, app-based ride-share outfits have emerged, their arrival like gasoline tossed on an already smoldering fire.

Mohamed says he came to the United States in 1996, when he was 20, after four years spent in a refugee camp on the border of Kenya. He escaped war in the camp, and met his wife there. The couple arrived in the U.S. with the typical dreams of freedom and prosperity. “America,” says Mohamed, “was heaven to me.” He’s now been driving a cab in Seattle for 13 years.

Articulate and full of passion, the 37-year-old father of two girls, 5 and 13, has become increasingly discontent with the city’s handling of the local taxi industry. Having long ago bought in as an independent taxi owner—saying he purchased his license with the proceeds of two stints spent processing fish in Alaska—Mohamed speaks with fire about “leveling the playing field,” the American Dream, and the difficulty he and his taxi brethren are having living it. Several times during our interview he urges me to “just be fair” with this article.

The backdrop of this ongoing drama is important. For several years, Mohamed says, he’s felt betrayed by the City of Seattle and its failure to enforce rules designed to regulate a flat-rate, for-hire industry that seemingly sprung from nowhere between 2011 and 2012. According to city code, meterless for-hires are restricted to prearranged trips; required to charge a flat rate; and barred from picking up hailed rides or trolling the city’s taxi stands. The license has existed for decades, but historically has been little used; in June 2007 there were seven active for-hire licensees. “People weren’t interested in them,” says Denise Movius of Seattle’s Department of Finance and Administrative Services, which oversees Seattle’s taxis and for-hires.

Recently, however, that number has grown. According to records provided by the city’s Consumer Affairs Unit, the number of active for-hire licenses in Seattle tripled from 2007 to April 2010, then skyrocketed from 50 in October 2011 to 199 by the time the rush ended in February 2012. The new for-hires entered a market that already included more than 700 limousines. Predictably, everyone is feeling squeezed. City officials offer only anecdotal explanations for the run on for-hire licenses, but the fact that a new Seattle taxi license hasn’t been released in 23 years surely played a part in creating the demand. (Because of this, the most prized of the existing taxi licenses can sell on the open market for as much as $250,000, according to the city—a shocking figure that underscores the investment at stake for taxi-license owners.)

More than a year after the rush ended, cabbies like Mohamed say the city is failing to enforce the restrictions against for-hires, allowing for what amounts, in longtime taxi driver Joe Blondo’s opinion, to armed robbery. “What’s the difference?” he asks, recounting a list of recent stolen fares he claims to have witnessed at the hands of for-hires. Blondo recently stepped down from the Seattle-King County Taxi Advisory Commission, an 11-member body with no regulatory authority that provides recommendations to the Seattle and King County Councils concerning issues that affect the taxi industry.

Considering the circumstances, Blondo’s scenario seems plausible. As of August, the city has three inspector positions, tasked with lording over 924 taxicabs and 358 for-hires. “The difficulty is we have limited inspectors,” says Movius. She estimates the city’s three inspectors spend 70 percent of their time on the ground, running “secret shopper”–style stings in which taxis and for-hire drivers are targeted for violations. Down to a single inspector for most of 2012, in that year the city issued only 49 violations to for-hire drivers. With two additional positions added late in the year, the 2013 total is expected to rise, though no one expects all violations to be caught.

“This is not fair,” says Mohamed.

For-hire drivers, naturally, don’t see themselves as the villains taxi drivers make them out to be. Samtar Guled, the manager of Eastside For Hire, also calls for a “level playing field.” He sees for-hires paying licensing fees and insurance costs in line with what taxi drivers pay, but restricted to a third of the business taxi operators have access to. “They have a huge advantage,” Guled says of taxi drivers. “Everybody should have an opportunity to earn a living, with the same requirements. . . . [Taxi drivers] want to have their cake and eat it too.”

Given the disparity, Guled says, it’s only natural that some struggling drivers would break the rules. The arrival of the ride-shares, he observes, has only increased the lawlessness. “The reason I think, frankly, is because we see the city not doing anything about Uber, SideCare, Lyft,” Guled says.

One of the few things for-hires and taxi drivers seem to agree about is that ride-shares need to be regulated. “Regulate for safety, make sure cars have insurance, and let the market sort things out,” Guled suggests.

Seattle City Council President Sally Clark is in the middle of the mess. The head of the council’s Committee on Taxi, For-Hire, and Limousine Regulations—which held its first meeting in March—she laughs and sarcastically calls herself “lucky.” Truth be told, Clark seems to enjoy wading into the murky waters of Seattle’s transportation industry, an area she describes as “probably the most complicated sector of business” in the city.

Whether she enjoys the position or not, Clark is sure to make enemies by diving into the fracas. Perhaps that’s the reason others are hesitant to talk too much about the budding legal and regulatory controversy surrounding taxis, flat-rate for-hires, and the upstart ride-shares. From the mayor’s office, all spokesperson Robert Cruickshank will offer is that Mayor Mike McGinn is “looking closely at the issue of ride-share companies, for-hire vehicles, and taxi regulation and enforcement,” while waiting on the results of the demand study to guide his decision-making. As to whether ride-shares like Lyft, Sidecar, and UberX are illegal in current form, Cruickshank says, “We don’t have a comment on that question at this time.” John Schochet, the deputy chief of staff at the City Attorney’s Office, is equally vague, pointing to existing city codes that define taxis and for-hires while saying “it’s a dynamic issue” with many of the “facts in dispute.”

Things are more certain when it comes to the $100,000 demand study, which is being undertaken by the Tennessee Transportation & Logistics Foundation in association with Taxi Research Partner. The results are expected to detail the use of and demand for taxis, for-hires, ride-shares, and limousines in Seattle—broken down by submarkets like street hails, prearranged trips, and hospitality trips. The study’s findings—which ride-share policy will in theory emerge from—were originally expected by July 11. Then the due date was moved back to early August. Now, according to Clark, a further delay has pushed the study’s expected release to Sept. 3. “I don’t like it, but if the study’s not ready, there’s not much I can do,” says the council president.

For Seattle to take its time and wait for the outcome of an expensive study before taking action isn’t unusual—it’s classic Seattle Process, carried out in the name of thoroughness. But that doesn’t mean Clark and others haven’t shown their hand when it comes to the fate of ride shares in Seattle. There seems to be broad agreement in City Hall that Lyft, Sidecar, and UberX fail to meet the RCW definition of “ride sharing,” which protects casual carpooling and individuals with special transportation needs using rides provided by social-service agencies or nonprofit providers.

“People like [the ride-share] interface. I like this interface! I think it’s cool. The whole level of trust and trusting the patron to click, choose, and give feedback is pretty amazing,” says Clark. “The part that looks exactly like a taxi, though, is the part where you sit on the seat and close the door. It’s the same deal; it’s the exact same service at that point. My gut feeling would be that we have to deliver a message to the [ride-shares] at some point here in the near future.”

Assuming Clark’s colleagues share this sentiment when the moment arrives to stop talking and cast votes—likely late this year or early next year—the question then becomes: Is there a way a regulated ride-share market can survive in Seattle?

“I don’t know yet. I like to think so,” says Clark.

According to Lyft co-founder and president John Zimmer and Sidecar’s Sunil Paul, it all depends. If Seattle wants to follow in the footsteps of the California Public Utilities Commission, which appears to be moving in the direction of regulating ride-share outfits for safety while creating a new classification for them—“transportation network companies”—then it could work. Under a proposal by the CPUC delivered July 30, ride-share companies would be licensed by the state and required to cover drivers with $1 million in liability insurance, while drivers would be required to undergo criminal background checks, receive training, and adhere to a zero-tolerance drug policy—all benchmarks Zimmer says Lyft already meets. But if Seattle decides to regulate the burgeoning industry in line with the way it rules over taxis and for-hires—with licensing fees and insurance costs pushed onto ride-share drivers—Zimmer and Paul both say it will almost certainly spell disaster for the companies here.

“[Sidecar drivers] are not taxi drivers. They are not able to accept a street hail. They don’t use a meter. They don’t use the terminology of taxis. They are not taxis, and any sort of sensible definition of the term taxi would not include them,” says Paul. “If the city tries to regulate it like a taxi, it will destroy these innovations.”

In a dress shirt and slacks, 29-year-old John Zimmer doesn’t look completely out of place in an upscale Pioneer Square coffee shop. He blends with the throng of young professionals who buzz through the city every day. He’s well-kempt and confident. He wants to change the world.

There are differences between Zimmer and the other smartphone-toting young ladder-climbers around us, however. Though you couldn’t tell it by looking at him, Zimmer’s 14-month-old company has roughly $80 million in venture funding behind it. As it has elsewhere, Lyft—which Zimmer co-founded with Logan Green, also 29—has taken off.

In town in late July for a series of meetings with City of Seattle officials, Zimmer is also the guy responsible for the pink mustaches you see affixed to the front of cars; the ironic auto facial hair defines the Lyft brand. In Seattle, Zimmer’s mustaches are everywhere this summer.

“You can blame me,” Zimmer says of the iconography. “There’s a company that makes these things, called Carstache. … We wanted to design happiness and joy into the full experience.”

Happiness and joy aside, Zimmer knows that plenty of questions remain concerning the safety of his business. But listening to Zimmer talk, Lyft starts to feel more like a grand vision for redefining transportation than a shot at taking down the taxi industry. Sure, he knows taxi drivers are unhappy and the city council wants answers, but he plays the good guy, a harbinger of the future.

“I empathize with anyone who’s negatively impacted by something, but at the same time, I strongly believe that the net of what we’re doing is very positive and very good,” says Zimmer, who left Lehman Brothers in 2008 to pursue his dream. “Things are changing. … It’s inevitable that these things are going to change, that transportation is going to change. That can be a really fantastic thing for everyone involved.”

Lyft dates to 2007, when Zimmer and Green created Zimride, a ride-share service targeted at college kids. After expanding to 130 college campuses across the country, the duo decided to reimagine Zimride over three weeks in mid-2012—giving themselves a fresh slate and the advances in mobile technology to work with.

Lyft and its mustache-clad cars were the result. And people have bought in. The company has raised more than $80 million in venture funding thanks to the investments of Andreessen Horowitz, Founders Fund, and Mayfield Fund, with The

Wall Street Journal reporting in May that Lyft has an estimated value of $275 million. San Francisco recently celebrated an official “Lyft Day” by order of the mayor.

“We’ve grown faster,” Zimmer says when asked to compare his company to his chief competitor, Sidecar, which is backed by $10 million in venture funding. He says the two companies have similar philosophies and are “marching along that same path.” Both are built on a suggested-donation payment system. “We’d been working as a team for six years,” Zimmer says when pressed on how he has been able to attract so much money.

Though cities like Seattle and states like California are still deciding what it all means, Zimmer says his company is growing; it now boasts 100 employees at its San Francisco and Oakland headquarters and operates in seven cities: San Francisco, L.A., San Diego, Chicago, Boston, Seattle, and, most recently, Washington, D.C.

In its first two months in Seattle, Zimmer says, Lyft’s market grew faster than in any previous city. Though Lyft never engaged in an expensive study before deciding there was a demand for its services in Seattle, the positive response from users doesn’t seem to surprise Zimmer. “This region is very innovative and open to green cities and the future . . . so we wanted to have a presence here,” Zimmer says. “We thought there was the type of people [in Seattle] who would be into this kind of community-powered transportation.” So far, he says, “there’s been a great amount of demand.”

The money and momentum behind Lyft allows Zimmer to think big. Having graduated from Cornell University’s Hotel School, he credits a “green cities” class during his senior year with his affection for ride-sharing. “I couldn’t comprehend a physical infrastructure that was coming after highways,” he remembers. “Our cities are built. Manhattan’s, like, 80 percent pavement . . . It’s going to be hard to escape that infrastructure.”

The a-ha moment, Zimmer recalls, can be traced to his hotel and hospitality background. “The major metric we always talked about was occupancy. So I was like, ‘OK, what’s the occupancy of these [car] seats that are all flying around?’ And it’s, like, 20 percent. Eighty percent of seats at all time are all empty. So then I’m thinking, maybe the next infrastructure is actually not physical, but information, about when those seats are empty and who needs those seats. That was the vision.”

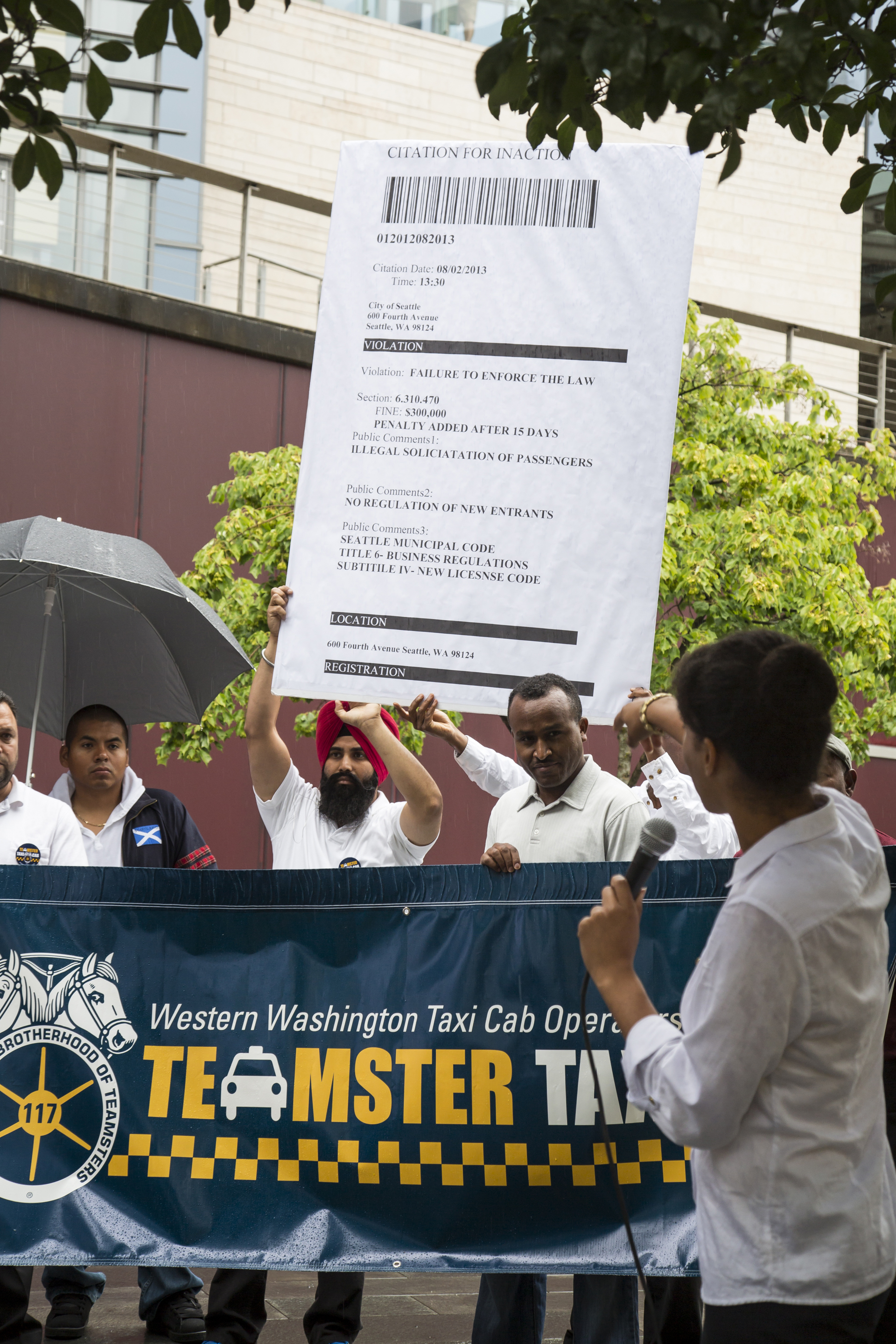

Like 500 other Yellow Cab, Farwest, and Orange Cab drivers, Salah Mohamed pays $25 a month for Teamster support. If getting heard is the goal, then it’s been money well spent. On August 2 the Western Washington Taxi Cab Operators Association, with help from the Teamsters, surrounded City Hall with cabs. Outside, angry drivers served a “Citation for Inaction” to the city council, alleging the city has failed “to enforce existing laws that protect taxi drivers and their families.”

Sally Clark was out of town on city business. Mohamad, however, was there, helping deliver the Association’s message. He isn’t a rookie when it comes to speaking to the media or pressuring city officials. One of 15 democratically elected members of the Association’s Leadership Council, he has recently become adept at both—made clear when he was quoted by the Times detailing the city’s alleged mistreatment. And a month earlier, when I called Teamsters 117 to get the union’s take on how ride shares have changed the game, Mohamed was called on to deliver the message.

Not all taxi drivers agree with the specifics of the message, however. Joe Blondo, for instance, who’s been driving cab for a quarter-century and says he makes a comfortable living working only two days a week, questions the numbers the Teamsters-backed Association uses to describe the plight of the low-wage driver, contending that the Teamsters are advancing an agenda in the interest of only a small number of owner/operators. Meanwhile, Dawn Gearhart, a business rep with Teamsters Local 117, says the Association’s numbers come directly from the driver/owner population, and estimates that the “majority of [drivers and owners] agree” with them. She says most start a week $1,000 or more in the hole.

Removed from this bickering, Mohamed drives us to the SeaTac Airport parking lot, where Yellow Cabs line up before being dispatched to the airport’s taxi line. The lot is full of drivers, many just as disillusioned as Mohamed by what they say is the city and county’s failure to protect them. Gearhart estimates Association members are 25 percent Somali, 30 percent Ethiopian, and 45 percent Indian. “It’s a real immigrant story,” says Leonard Smith, Teamsters Local 117’s director of organizing and strategic campaigns.

Sitting in Mohamed’s yellow Prius, with two other angry drivers having joined us in the back seat, the focus turns to the ride shares. “Why would you pay for dispatch, why would you pay a lease, why would you have to go to the city to pay fines or fees when you can get it for free?” Mohammed says of the Sidecars and Lyfts of the world. “We need nothing but a level playing field. There’s nothing wrong with competition, a competitive business. But the problem is when you have a certain group that’s free to do whatever they want.

“The way I see it, the city already deregulated everything,” he continues. “Anybody can do whatever they want, and they can get away with it. . . . Instead of rewarding us, saying these people are doing the legit things—no, we’re being harmed because of that. That’s just sadness.”

“It’s a bit of a wild West out there, and people’s lives are at stake,” says Smith. “We’re looking at disruptors [ride-shares] in a marketplace that has probably needed some disruption, because of the way it’s been functioning. [With taxis,] You’re dealing with technology that’s 50 years old. . . . If people want to use [ride-share services], they should have the opportunity to use them. But they should be operating under the same competitive restraints and restrictions that meter taxis operate under. Otherwise you’re essentially disenfranchising thousands of people from being able to make a living.

“It’s getting pretty hot out there,” Smith says of the growing tension, which is only stoked with each day of inaction from the city.

Alicia Ortiz pulls up to the corner of Boren and Thomas and we pick up John (not his real name), the Amazon employee heading for the Showbox, who says he uses Sidecar about once a week. Without hesitation, John hops in the front passenger seat and asks Ortiz how her day has been. It doesn’t feel like a taxi ride.

“It’s been stressful,” Ortiz tells him. “I’ve been planning a lot of events for work.”

When there’s a break in the small talk, I ask John why he likes Sidecar. “I try not to pay for rides when I can use my bus pass,” he says. “I use [Sidecar] mainly when it’s late at night, when I don’t want to get in the line for the bus, and hang out for a while. I can just sort of drop a pin [request a ride through the app] and hang out with my friends for that 10 minutes until someone rolls up, and then I’m ready to go. So it’s great. It’s really great.”

After dropping off John at the Showbox, our second ride request comes quickly, from Alki. Ortiz perks up at the chance of a $22 fare. She tells me her average is closer to $15. You get the feeling this could become addictive.

“Right?” Ortiz exclaims when presented with this observation. “Because it’s fun. When you start getting rides, you’re like, ‘Why would I go in now?’ ”

Admittedly, however, it’s not all sunshine, rainbows, and “vibing to the radio” on the road, as Ortiz puts it. Like taxi customers, she says, at times her riders leave something to be desired. “Sometimes I pick people up when they’re drunk … I mean, they’re drunk,” she says, calling such situations rare. “One guy was, like, hanging out the back of my window, and I just had to be, like, ‘Hey, man, this is still my car.’ ”

There are also the natural fears that come with giving rides to strangers—something Ortiz says using the Sidecar app helps alleviate. “When you’re driving around at night—I mean, I’m a girl,” Ortiz offers. “So I usually keep my bag under my seat. And if I ever go to a neighborhood I don’t know, I’ll usually wait with the hazards on. And if I feel like I see [the rider] walking up, I’ll call them, so that they answer, so I can confirm that it’s them. … This is my car. I only do what I’m comfortable with, and I wouldn’t let someone in my car that I don’t feel safe with.”

We pick up our second rider, a young professional who says she works in PR and runs a local cannabis magazine. We’ll call her Kelly. A Sidecar regular, it’s clear Kelly and Ortiz know each other.

“Hey, what’s up, lady? Thanks for picking me up!” Kelly says, hopping in the front seat. She’s headed downtown, to Urban Outfitters.

“It’s cheaper than a cab, and everyone’s nicer,” Kelly explains when asked why she uses Sidecar. She says this is her second Sidecar trip of the day, and that often she knows her driver. “A lot of the drivers I’ve had I’m pretty familiar with. So I feel like I’m connecting with actual people. … They’re just normal, day-to-day people doing this as a nice favor, and also making some cool cash on the side, which I think is awesome and that’s why I want to support it.

“Because when I get a car, I might do it too.”