The most classified program at Microsoft isn’t an operating system. It isn’t a Web browser. It’s a 9-year-old boy named Rupert.

When Microsoft executives talk about fear, they often use the phrase “garage factor.” The term comes from computer history, which is full of stories about code geeks hatching the Next Big Thing in their parents’ basement, and it refers to the possibility that a new product or company might come out of nowhere, overnight, and crush the industry’s dominant corporation. In other words, do to Microsoft what Microsoft did to IBM. “Bill Gates’ greatest fear is not that some kid is brewing the next killer app in his garage in Kenosha,” says Robert Warburg, an analyst with the Bay Area venture capital firm Klein & Fairfield. “His greatest fear is that some kid will brew up the next killer app in his garage in Kenosha and Microsoft won’t own it.”

The US Justice Department’s antitrust suit against Microsoft can be seen as one consequence of the software giant’s fear of garage factor. “When [Netscape] Navigator hit the market in ’96, all of a sudden this garage factor X became real,” recalls a former product manager who worked on Microsoft’s rival product, Internet Explorer. (In the Justice Department suit, which is still being argued in court, Microsoft is charged with unfair business practices in an effort to sink Navigator.)

Chastened by their experience with Netscape, Gates and a small circle of top executives—including company president Steven Ballmer and chief technology officer Nathan Myhrvold—met in the fall of 1997 to find a way to co-opt the garage factor. What they came up with is a program whose existence has been known, until recently, only to an elite cadre of Microsoft vice presidents. Instead of buying start-up companies whose innovations might be a threat to Microsoft, the company would, as one executive reportedly put it, “leap two rungs up the food chain.” Under the code name “Manchuria,” Gates gave the green light to a program that would identify child prodigies and bring them under the proprietary wing of the Redmond software giant. In exchange for stock options that ultimately may be worth anywhere from $5 million to $100 million, Microsoft would care for, house, feed, and educate the children until the age of 18. “If they’re going to invent the next Apple or Linux,” says one executive, “they’re going to do it in our garage.”

On the face of it, the idea sounds insane. And indeed, Manchuria has been slow to get off the ground. There’s only one entrant in the program so far. But since his arrival in Redmond early last year, he’s been the subject of endless in-house e-mail gossip. One string of messages debates whether he’s a Mozart-level genius. Another lays bets on when he’ll occupy Bill Gates’ chair. A third questions whether the program, and the entrant, even exist.

The doubters can relax. Three things about Manchuria are now known for certain. The entrant exists. His name is Rupert Tollefsen. And Rupert is 9 years old.

A black budget job

“I don’t know who told you that, but I’ve never heard of any such program. Or person. We get a lot of weird rumors around here, but that’s one of the weirdest.” That’s Microsoft spokesman Emmett Richter, filling in for an antitrust-weary Mark Murray. And he may well speak the truth. That is, he’s never heard of Manchuria. The program operates completely off the budget books. Even Microsoft’s chief financial officer is said to be unaware of its existence.

“You have heard of the Pentagon’s ‘black budget’? That is the model upon which the program is based,” says Vikram Narayan, a former research fellow at Microsoft’s research center in Cambridge, England. Narayan (not his real name), who left Microsoft earlier this year, was brought over to Redmond in December 1997 to get Manchuria up and running. He agreed to talk about the program only if his name was not used. “Everyone who contacts Rupert is subject to double-secret nondisclosure agreements,” he explains. During Tollefsen’s first weeks on campus, one of Gates’ personal assistants was assigned to tail the boy and secure NDAs from everyone he talked to. That duty has since been eliminated. “They realized they could not shut everyone up,” Narayan says, “so they concocted a cover story about Rupert being Bill Gates’ nephew.”

A day in the life

Although Microsoft officially denies his existence, if you happen to stroll by the northwest entrance to Microsoft’s Building 8—where Chairman Bill works—on a weekday morning around 5:30, you may catch a glimpse of a sandy-haired boy entering the well-guarded premises. With his unkempt bowl cut, black jeans, and Airwalk sneakers, Rupert Tollefsen looks like a shrunken version of a Microsoft programmer, minus the goatee. He swings a Buffy the Vampire Slayer lunchbox, which is full of Magic: The Gathering cards, not food. Lunch is always ordered in: a peanut-butter-and-potato-chip sandwich, two cans of Mr. Pibb, and a Rocket Pop. Some days Gates joins him, some days not.

According to Narayan, Tollefsen works two doors down from Gates himself in a room that’s less an office than an electronic playroom. “He must have 20 computers in there, in various states of dismantling. The place is a nest of wires. Some days it took me 15 minutes just to find Rupert.”

Every Monday morning, workers from Vanstar, Microsoft’s corporate hardware supplier, deliver a fresh Dell PowerEdge processor and Precision 610 workstation—a screaming $10,000 Pentium III package—to Rupert’s office. By Tuesday afternoon the machines have been stripped, their plastic housings piled in the corner like discarded husks. Narayan set up a credit account with the local Radio Shack so the boy could order any part the software company’s warehouse couldn’t supply. “He sticks mainly to phone components, bulk wire, that sort of thing,” says Radio Shack sales associate Scott Roberts. “Nice kid. Never gives his address.”

At precisely 3:20 every afternoon Tollefsen bounds out of Building 8 into the back seat of a company Lexus LS 400 and is driven to Microsoft’s unofficial watering hole, a Red Robin restaurant a mile from campus, where he devours a Mountain High Mudd Pie. Members of the waitstaff, who know him as “Rupe,” turn the bar’s three TVs to Channel 11 so he can watch Pokemon, his favorite show. Then it’s back to Building 8 until 6:30, when the boy genius calls it quits for the night. He climbs into the Lexus and is driven to the Issaquah home of his host family.

The Buddha comes to Barcelona

“Let me ask you something,” Roberts, the Radio Shack salesman, says to me as I put away my notebook. “Why’s this kid so important?”

The answer, according to Narayan and others, is that Rupert Tollefsen isn’t like one of those high school kids who’s so smart he goes to college when he’s 13. “Manchuria is itself merely a cover for a deeper program,” insists Narayan. That program, according to Narayan and another source, also has a code name: Barcelona.

“With a Castilian ‘th’ for the ‘c,'” corrects Narayan.

Like Tibetan Buddhists who seek out the one true reincarnation of the Buddha, Microsoft staff assigned to Barcelona have but one task: Find the next Bill Gates. In Rupert, they think they have Gates’ next, well, incarnation.

“The problem with Microsoft is that Gates has set up this culture in which the smartest man rules,” says Russell Meyer, publisher of the computer industry zine Faster Machine, Kill! Kill!. “So whoever follows him has got to have off-the-scale intelligence. That person also has to prove himself to the code jocks. It isn’t enough to be Marilyn Vos Savant.”

Therein lies the challenge for young Mr. Tollefsen. According to a series of intelligence tests administered by Microsoft, the boy has more brains than a sackful of owls. But he hasn’t proven squat to the programmers in the trenches. Yet.

“Barcelona isn’t a two-year investment, it’s a 50-year investment,” says Narayan. “But it will probably pay off within the next 10 years.”

How? The theory goes like this, says Narayan. Businesses operate in cycles. Boeing has seven-year upturns and seven-year downturns. Nike has 10 good years when Air Jordans are hot, five bad ones when everyone wants hiking boots. “Bill knows Windows is about to peak,” he says. “Microsoft has to consciously let itself go out of fashion for a few years in order to come back in fashion about the year 2005.” In its long-term plans, Narayan believes, Microsoft has all but conceded the next five years of the operating system market to Linux, the source code pioneered by Finnish programmer Linus Torvalds. (In recent months, IBM, Intel, and Oracle have all announced plans to support Linux-based software.)

The year 2005: That’s where Rupert comes in. Microsoft is betting that the technology that will ultimately render Linux obsolete is something called TR, the acronym for Thought Recognition. Using a complicated set of electrical impulses and biofeedback responses, a TR-driven machine accepts commands directly from the computer user’s brain. If you want to open a certain Word document, for instance, the TR operating system senses the desire and, without having to be told, opens the file. If the user, while working in that file, wonders, ‘How’d my Amazon stock do today?’ the TR would immediately open a small window with the current Amazon.com quote, downloaded from the Internet. In conjunction with software like Outlook Express, a user might eventually be able to send friends and relatives “telepathic” e-mail.

“The idea’s been around since the 1970s,” says Daniel Rabelli, a computer science professor at the Carnegie-Mellon Institute of Technology. “We joke about it around here. We call it ‘Firefox wiring,’ after the Clint Eastwood movie.” (In that film, a Russian MiG fighter picks up commands directly from its pilot’s brain.) Pentium-era computers are powerful enough to accept such complicated sets of instructions, Rabelli adds. “The trick nobody’s figured out yet is how to pick up signals from the body.”

Nobody, that is, until the day Rupert Tollefsen began tinkering with the TV remote.

Grandma and the cranial clicker

Folks in Soap Lake, a small community in central Washington, miss Rupert. “Ain’t been the same since he left,” says John “Buzz” Rorabaugh, a local barber and proprietor of Beauty by Buzz, a shop whose 1973 Zenith has received free HBO since the day 6-year-old Tollefsen modified it with clipping shears and a hank of old speaker wire. Tollefsen’s technological gift was well known before he left for the bright lights of Redmond. A group of Soap Lake High School seniors once bet Rupert he couldn’t rewire the basketball scoreboard to spell “EPHRATA SUCKS.” Rupert won the bet.

Nobody misses Rupert like his mother and grandmother, though. “I talk to him every night on the phone, but talkin’s not seeing,” says Roberta Tollefsen. “But I guess when the richest fellow in the world says your son’s the anointed, who’m I to argue?” Mrs. Tollefsen, who divorced Rupert’s father six years ago, lives with her 67-year-old mother in a cedar-sided cabin 6 miles outside of town. It was the elderly woman’s arthritis that led to Rupert’s big break.

“Mom’s arthritis got to the point where she couldn’t even turn on the TV,” explains Roberta Tollefsen. “You know how she hates to miss her Judge Judy.”

Rupert set about to solve the problem. Working with the remnants of an old biofeedback machine discarded by a local drug store, he rewired the TV remote to pick up commands directly from Grandma’s brain.

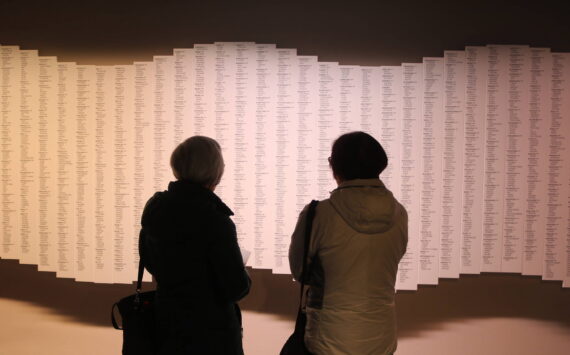

His inventing career might have ended there were it not for a photo in the local paper. The Soap Lake Tribune ran a page-one shot of Grandma wearing what the paper dubbed “Rupert’s Amazing Cranial Clicker.”

The next morning, Rupert’s Amazing Cranial Clicker was the talk of the Barcelona team. The Soap Lake Tribune feature had been caught in the Barcelona computer’s overnight Lexis-Nexis sweep. (Every morning, staff members sift through the search engine’s hundreds of mentions of words like “child,” “technology,” “genius,” and “develop” from newspapers around the world.)

Two days later Rupert and his mother met with Bill Gates and the Barcelona team in Building 8. “We told her to think of it as sending Rupert to a fancy private school,” recalls Narayan. “How did Bill put it? ‘Like Lakeside with stock options.'”

Roberta Tollefsen wasn’t convinced. Rupert was her only child. “That’s when Bill started telling her about the stock options,” says Narayan. It sealed the deal. Sources close to the project estimate that Tollefsen’s options could be worth $100 million in less than 10 years. “That’s a lot of new cedar siding,” adds Narayan.

Vampires, jeans, and infinite loops

It is difficult to talk to Rupert Tollefsen now. His adult escort/bodyguard has been upgraded from part- to full-time since Microsoft was alerted that a reporter was looking into the Manchuria program. But bodyguards are human. They too have to pee. Especially when they drink bottomless Cokes at Red Robin.

During one such moment recently, I sat at the bar and asked Rupert how the project was going.

“Commercial,” he said.

“Beg your pardon?”

“Wait for the com-mer-shull,” he said. I waited, and watched. Eyes fixed on the Japanimated exploits of Pokemon, Rupert sat on his barstool and rocked, ever so slightly, like a boy in a trance.

When an advertisement came on, I prodded him using the code name Narayan had told me Microsoft used for TR development. “How’s Oslo?”

“Terrible,” he said without looking at me. “My biocommands keep getting stuck in an infinite loop. It’s hopeless.”

“Sounds like—”

“Why do you wear stupid pants?” he interjected.

“What?”

“Those stupid pleats. They don’t do anything. You should wear jeans like me. I’m probably the most committed jeans wearer.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah. I like black jeans. I don’t care what brand. I hate green jeans, which my mom bought for me once.”

“What else do you like?”

“Diablo,” he said, naming a popular computer game. “And vampires. I know what kills ’em, what stuns ’em, stuff like that. Stuff most people don’t know.”

Before I could ask him another question, Pokemon returned and so did the hired beef.

This is your brain after strip-mining

Not everyone is thrilled to hear that Microsoft is in the TR game.

“We’ve picked up early rumblings about this technology,” confirms Jacob Heilman, executive director of the Bethesda, Marylandbased Foundation for Online Privacy, which is currently involved in the dispute over so-called “ID numbers” in Windows files and Pentium III chips. “If it’s true, it represents an enormous step backward in terms of personal privacy. Whatever software company gets there first will have the capability to strip-mine your brain.”

What especially concerns privacy watchdogs like Heilman is the possibility that Rupert Tollefsen’s TR operating system, if such a thing can be created, might contain not only the ability to pick up signals to the brain, but to feed them to the user’s brain as well. Researchers who have worked on proto-TR projects say this capability—known alternately as “complete-loop functioning,” or “reciprocity”—is the Holy Grail of 21st century information technology.

“Once you reach reciprocity,” says E. Claire Winchell, director of Kansas University’s Cognitive Science Project, “you’ve eliminated the last barriers between machine and user. Assuming that all machines will be directly linked to the Internet, everyone will be linked to everyone else.” At this week’s “Computers, Freedom + Privacy 1999” conference in Washington, DC, Winchell is scheduled to present a paper hypothesizing about a TR-run civilization 20 years hence.

“What we’re talking about is becoming Borg,” Winchell says. “But Borg with a friendly face.”

Tutorials with Buffett, talking shop with Allen

Around Building 8, TR is known as “Totally Rupert.” Most new technology at Microsoft originates in one of the company’s two research labs and is harnessed to a team of up to a dozen project managers. The company is so confident in Rupert Tollefsen, however, that it’s issued a confidential memo to other researchers: Hands off TR. Oslo will succeed or fail with Rupert alone. “If they’re serious about this kid taking over for Bill Gates,” says one industry analyst, “he’s got to come through with TR by himself.”

“And if he does,” adds the analyst, “we’re talking Edison, Graham Bell—the big leagues.”

Of course, Microsoft didn’t come to dominate the information technology field by inventing fantastic new devices. It rose to power through Gates’ unique ability to see the moneymaking potential of emerging technologies. Gates and his Barcelona team are already working on that angle. According to several sources, in February Rupert began once-a-month tutorials with renowned investor and Gates confidant Warren Buffett. According to those sources, Rupert has already taught Buffett a great deal.

The average age of Microsoft employees is much younger than most corporations—somewhere in the late twenties—but it still can get lonely for a boy of nine years. That’s why the Manchuria team continues to recruit new entrants. “Most of them won’t even get a second look from the Barcelona team,” reports Narayan, “but they give Rupert somebody to play with on weekends.” Most Saturdays, Rupert and a handful of Manchuria entrants can be found playing Warhammer 40,000, a role-playing game, in a Microsoft cafeteria. Once in a while they talk an adult into driving them to Games & Gizmos, a nearby game shop. (Once in a while that adult happens to be Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who is said to enjoy talking shop with Rupert.)

Open sourcerers

For every new market that Microsoft captures, it also adds to the army of Redmond rebels, those software radicals and conspiracy theorists who hear the voice of Beelzebub in every cough and burp emitted by the company. These are the folks who once believed Microsoft really could take over the Catholic Church. In the past few weeks, Rupert has been no. 1 on their list of Reasons Microsoft Is the Root of All Evil. “Re Rupe: How many more days will pass b4 MS starts cloning babies for the cyborg market?” asks one of the company’s detractors, a person identified only as “Avatar Josephinus,” in a message posted last month on the Usenet newsgroup alt.microsoft.mustdieaslowpainfuldeath.

These Windows squashers are considered mostly harmless by the company—”a bunch of Mac zealots and Linux hippies,” one Microsoft exec says. But in the case of Rupert and the Barcelona project, they may take the unprecedented step of going off-line and pursuing direct action.

“We know what he’s working on, and we don’t have a problem with it,” says a software activist known as JAKE (he insists on all caps), with whom I’ve exchanged e-mail about Rupert since last December. “We’re not a bunch of neo-Luddites. Somebody’s going to crack TR, and better that Rupert does it than the Pentagon.” Better that it’s in Rupert’s hands because JAKE and his colleagues have, he adds significantly, “access.”

“We’re gamers,” he says, referring to his taste for role-playing games like Warhammer 40,000. “We’ve got face time with Rupert every weekend.” And what they plan to do with that time might send shivers down Bill Gates’ spine. They want to convince Rupert, after he’s cracked the TR mystery, to do the unthinkable: open-source it.

Source code is the DNA of any operating system, like Windows. It’s the millions of lines of instructions that tell the computer what to do. Microsoft makes money because it holds the secret source code to Windows—and, the company hopes, to TR. If JAKE and his fellow travelers get their way, the TR source code would be released into the public domain for all to use and adapt, free of charge. Linux is an open source operating system. Its creator, Linus Torvalds, is a cult hero. He is also not a rich man.

Strange disappearance

Microsoft won’t let TR be open-sourced without a fight. In late January, JAKE began receiving e-mail correspondence from Microsoft’s legal department ordering him, under threat of civil action, to cease and desist all contact with Rupert. (The company knows JAKE exists in cyberspace, but does not know—nor do I—who he is in meatspace.) JAKE responded with a series of passionate, if sophomoric, screeds attacking Microsoft. The exchanges escalated until early March, when all messages from the lawyers suddenly ended. “I’m a little spooked,” JAKE wrote me. “No warning, no ultimatum—nothing.”

I haven’t heard from JAKE in two weeks. I send him e-mail twice a day and post messages on six different anti-Microsoft Usenet sites. His online friends profess no knowledge of his whereabouts, and have taken to writing e-mail in code when talking about their missing colleague. Some suspect that he’s been “disappeared,” others believe the company made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. “Make NO MISTAKE,” wrote one poster to alt.microsoft.mustdieaslowpainfuldeath last week, “JAKE is a very rich man today. Options can sway even the most COMMITTED HEART.”

Meanwhile, in Building 8, Rupert Tollefsen goes about his daily business, seemingly oblivious to the storm surrounding him. He won’t say whether he’s two days or 20 years from realizing TR. He’s happy because he’s got a new pair of jeans and a new deck of cards in his Buffy box—and a planet full of willing minds, waiting to be mined.

Correction

There were a number of errors in the 4/1 cover story on Microsoft’s Thought Recognition technology. Robert Warburg, an analyst with the Bay Area venture capital firm Klein & Fairfield, does not, as was implied in the article, exist. Nor does Klein & Fairfield. Microsoft has never employed Vikram Narayan, who does not exist. Workers from Vanstar do not deliver Dell PowerEdge processors and Precision 610 workstations to Building 8 every Monday morning. Microsoft does not keep an account with Radio Shack. Radio Shack does not employ an individual named Scott Roberts. The waitstaff at the Redmond Red Robin does not turn the bar televisions to Pokemon every afternoon. Russell Meyer does not publish the zine Faster Machine, Kill! Kill! Carnegie-Mellon Institute of Technology does not employ an individual named Daniel Rabelli. There is no newspaper called the Soap Lake Tribune. There is no such thing as the Foundation for Online Privacy based in Bethesda, Maryland. The Kansas University Cognitive Science Project does not employ E. Claire Winchell, who does not exist. Nine-year-old genius Rupert Tollefsen does not exist, although the editors would like to thank Andrew Rowny, his mother, Lori Larsen, and his grandmother, Greta Larsen, for lending his presence to our writer, Bruce Barcott, and photographer, Rick Dahms. Seattle Weekly apologizes for these, and other, unregrettable errors.