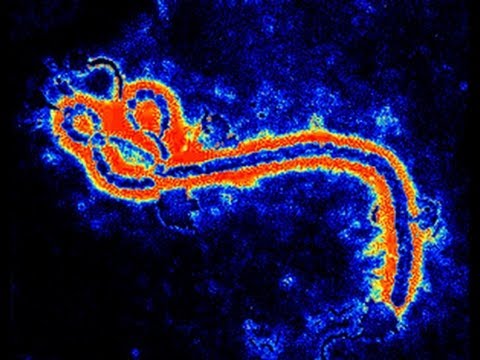

Last week, Scott Lindquist, the state Department of Health’s communicable disease epidemiologist, led a meeting with the health officer of every county in the state. At that point, several other states had announced mandatory quarantines for anybody coming into the country after visiting Ebola-affected countries in West Africa. The issue had blown up after a nurse who had treated Ebola patients in Sierra Leone returned to the U.S. and found herself quarantined for days in an unheated tent in New Jersey, and then taken to Maine, where she was again ordered quarantined against her will.

Did Washington state want to follow suit and start imposing quarantines? The health officers discussed at Lindquist’s meeting. The resounding answer was no, according to the epidemiologist.

Only the night before, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had come out with its guidelines for handling people coming into the U.S. from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. The CDC recommended not quarantines—which many in the scientific community believe to be counterproductive since it would likely discourage health workers from volunteering in West Africa—but what Lindquist calls “active monitoring.”

That was the approach Washington state had already adopted in an interim policy some four weeks ago, and it was the approach that local health officials decided to stick with.

As Linquist indicates, it is not exactly laissez fair, especially in this state. If the DOH determines that someone is at risk of developing Ebola, that person will receive a visit from a local health official at least once a day—and in many cases twice a day, at least initially—during a 21-day period of monitoring. That’s so the official can take the person’s temperature and look for other symptoms of Ebola.

Health officials also instruct the person under surveillance to stay away from public gatherings, like a movie or play, and taking any kind of public transportation. A bike ride in the woods is just fine, though, Lindquist says.

The DOH has kept this monitoring relatively quiet, probably in part because it has not monitored that many people—11 in all. Five of those have finished their 21-day period of observation, while six, as of this past Tuesday, are still being monitored, according to Lindquist.

That represents all the people who have recently come into this state from the three countries at issue. (The DOH knows because it gets information from federal health officials who do an initial health screening at the five airports around the country that those returning from West Africa are allowed to fly into. “There are no flights directly into Washington state,” Lindquist says.) Despite the presence of high-profile aid organizations here—the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, PATH, World Vision—we’re not getting a lot of people coming here after volunteering in West Africa. “That is a little surprising that the number is so low,” Lindquist says.

None of the 11 have developed symptoms of Ebola, according to the epidemiologist.

Also quietly, a DOH lab in Shoreline on Saturday tested a blood sample of someone from Oregon who was suspected of having Ebola. The facility is one of 13 public health labs around the country that are doing such tests, and the staff involved had to don protective clothing and take other stringent safety measures. “It went very smoothly,” Linquist says. The test came back negative for Ebola.

So the state, so far, seems to have largely escaped the torturous Ebola policy debate that has hit other parts of the country, which is not to say that some people might not be surprised by the policy there is. Lindquist notes that he heard a health worker on the radio the other day talk about how he was going to volunteer in Sierra Leone and then come back and hole himself up in a hunting cabin for three weeks. “I hate to tell you,” Lindquist says, alluding to the mandate of twice-daily monitoring, “but I don’t think you are.”