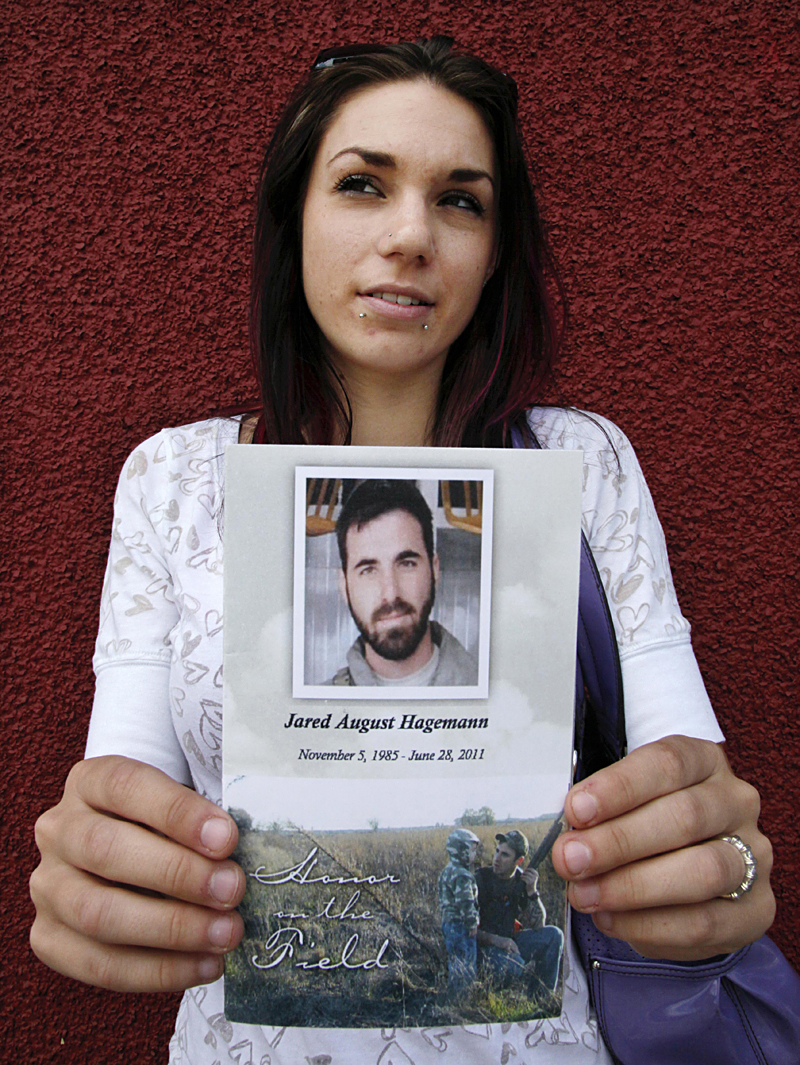

Ashley Joppa-Hagemann arrives at a coffeehouse outside the gates of Joint Base Lewis-McChord carrying a toddler. With red streaks in her dark hair, two piercings below her lip, and an outfit of jeans, a T-shirt, and flip-flops, the 25-year-old looks impossibly young for the role she has recently assumed: widow.

Ashley is here for a late-September press conference about the “base on the brink,” as the gathered activists call it. Eleven soldiers stationed at JBLM have died in presumed suicides since the beginning of the year—all evidence, they say, that the military, despite its professed desire to stop the stateside carnage that is afflicting its ranks, isn’t serious about the problem.

There are veterans on the panel, including one with a moving story to tell about his post-battle mental-health problems. But on this September morning, Ashley’s story holds the emotional center of the room.

On June 28, her husband, an Army Ranger named Jared Hagemann, was found lying in the bushes in a JBLM training area, a few feet away from his truck. Jared was dead, with a bullet wound to the head. And while the military hasn’t ruled the death a suicide yet—two investigations are still underway—his wife says she is certain that he killed himself. She’s also certain about who is to blame.

“The military did not take care of my husband,” Ashley tells the assembled crowd, which includes reporters from KOMO-TV, KUOW, and the Los Angeles Times. Commanders “don’t listen to the soldiers. They are not there for the soldiers. They are merely there to push these men to war.”

As Ashley recounts, her husband said again and again that he was having problems, and couldn’t face another deployment. By her reckoning, he had already served a staggering eight tours overseas, and was scheduled for another in August.

Yet, she says, “the military pretty much told him he couldn’t leave.” They didn’t even allow him to get help. “That’s just an excuse to get out of work,” she says his commanders told him. If he wanted counseling, he’d have to do it on his own time.

“As a widow, it is my goal to make sure another family doesn’t have to go through this,” she continues before trailing off and starting again with a quiver in her voice. “Every day is a struggle now for me. But now I don’t have my husband to help me.”

The room goes quiet. One of the veterans on the panel seems to fight back tears. He goes on to cite Jared as a prime example of military neglect, and of its policy of returning traumatized soldiers to the battlefield, not once but repeatedly.

The assembled press, too, are quick to pick up on Jared’s symbolic value at a time of spiraling soldier suicide rates, which have more than doubled nationally since 2001. Just this past July, the Army saw 32 suicides, a record.

“Widow: Ranger killed self to avoid another tour,” read the Seattle Times headline that followed Jared’s death. The story reached the UK via the Daily Mail, which ran it with a quote from Ashley about Jared’s ostensible feelings of guilt for what he had done overseas: “There was no way that any God would forgive him.”

I followed a similar story line for this paper in my initial reporting, quoting a national veterans’-rights group called March Forward! that said the Army refused to give Jared the help he sought over and over again. March Forward! subsequently started an online petition to demand that Jared’s chain of command be held accountable for his death.

But as I continued to research the story over the next few months, I found that the picture that emerged from the coffeehouse press conference and media accounts was incomplete and inconsistent with some important facts. Among them: Jared wasn’t stop-lossed or otherwise forced to stay in the Army. He actually re-enlisted twice, most recently in January when he was in Afghanistan—his sixth deployment, not his eighth, according to the Army—and signed up for six more years.

“Jared absolutely loved being an Army Ranger,” says his sister Haley, declining to talk in detail until “more loose ends are tied.” Jared’s childhood friend Miranda Johnson, who talked by phone with the soldier frequently over the past year, agrees. She says he told her that he felt more at “home” with his fellow Rangers overseas than he did in his real home.

Yet that’s not the full story either. A review of medical and police records, along with interviews with Ashley and those close to her and Jared, suggests that it’s far too simplistic to blame his death entirely on military neglect and pressure. Jared was haunted both by his wartime experience and by the situation he found himself in when he came back, shaped by self-destructive behavior, family strife, and an equally troubled economy that had no ready place for a soldier looking to put combat behind him.

Jared’s story is a case study in the many pressures that bear down upon soldiers in wartime. As if the trauma of war weren’t enough, there’s the necessity of fitting back into your pre-combat life, though you’re not the person you were before. It’s a situation tens of thousands of troops will soon face as the U.S. pulls out of Iraq by the end of this year.

Throw weapons and booze into the mix and you’ve got a recipe for rage and violence, not only on your part but on the part of those around you. And when you can’t or won’t get out, the consequences can be devastating.

“From the time he was a little boy, he always dreamed of being in the military.” So reads Jared’s obituary, written by his parents and run in The Modesto Bee, a paper which serves the small central-California town of Ripon where he grew up. (His parents did not respond to attempts to reach them.)

It’s likely Jared was drawn toward the Army’s rugged lifestyle. Tall and good-looking, with dark hair and eyes and, in later years, a beard, he hunted, fished, and played sports, including football and baseball. Miranda Johnson recalls that every Thanksgiving Jared’s dad would take him pheasant hunting. “The dirtier he was, the happier he was,” she says.

Jared graduated from Ripon High in 2004, just a year after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and joined the military that November. Soon after basic training he became a Ranger, part of the Army’s Special Operations Forces. Posted to Joint Base Lewis-McChord, he went to a barbecue where he met a pretty young single mother, Ashley Joppa, who had just given birth a couple of months prior. They were both 19.

“He was very charming,” recalls Ashley. “He was outgoing, an avid outdoorsman.” And, she notes, his affiliation with the Rangers—elite units sent on especially dangerous missions—meant he didn’t have to have a normal soldier’s “stupid haircut.”

Her mother, Heidi Joppa, remembers the first time she met her future son-in-law. She took to him immediately. “He was really a gentleman,” she says. Her husband, who had spent more than 20 years in the Army, also formed a close friendship with the young soldier.

Jared’s parents, however, were wary of their son’s new girlfriend, according to Ashley, warning him that as a single mom, she might be using him. “Oh, yeah,” she says she told him. “You’re in the military. I’m using you for your paycheck.” Jared disregarded his parents’ warnings. Within a year, the couple had wed. And in December 2005 he headed out on his first deployment, to Iraq.

Jared proved an excellent Ranger. One evaluator put him in the “top 10 percent of all junior NCOs [non-commissioned officers] I have seen over 13 years of service.”

Accolades aside, according to Ashley, when her husband came home he was a different person. “His eyes were lifeless, like he was checked out,” she says. “He turned to substance abuse. He would not talk. He didn’t really have any friends anymore. It was just me and him, and then me and the kids.”

“Even going to the grocery store . . . he did not want to go,” she says. “And if he did, he would have his .45 in his holster.”

Ashley says he did eventually share a few of his experiences. On one occasion, a buddy took his spot on a mission and was killed. “That should have been me,” she says he told her, crying.

On other occasions, she says, he had been sent to a house where a “person of interest” was said to dwell. He and his fellow Rangers would order everyone out, and find a crowd of mostly women and children, but also a few men with guns. Often, the person of interest was not among them.

“Put your weapons down or we’ll have to shoot,” the Rangers would announce nonetheless, as Ashley tells the story. Invariably, the men would hold onto their weapons, and the Rangers would shoot. “I don’t fucking get it. All they had to do was put their guns down,” Ashley says Jared told her, trembling.

She says her husband’s most haunting moral quandaries, however, concerned Iraqi and Afghan children. The Rangers, she says her husband told her, were ordered to shoot gun-carrying youngsters, no matter how old, a point which a Rangers spokesperson vehemently disputes.

Ashley isn’t precise about any particular incident, however. Indeed, when asked where Jared was during any given deployment, she can’t remember. “Afghanistan,” she says at one point. “I don’t know—one of them.” At times, she seems dazed. “I’m sorry, where was I?” she’ll say after stopping in mid-sentence. “There’s just so much.”

But whether or not he ever killed a child, something Jared experienced disturbed him deeply.

In May 2009, a week after his return from a tour in Afghanistan, he checked into JBLM’s Madigan Army Medical Center. According to hospital records, he reported having “intrusive memories, nightmares . . . and emotional detachment starting following his first deployment and getting progressively worse through subsequent deployments.” Also getting worse following his deployments (which by then numbered four) was his alcohol use. Worse, he had been having thoughts of killing himself.

Diagnosed with PTSD, Jared admitted he had been reluctant to seek care in the past. Now, however, he expressed interest in a virtual-reality program pioneered by Madigan. The computer simulation brings soldiers back to the battlefield in an attempt to get them to relive and overcome their trauma.

Yet by July, he had not signed up for the program, according to the records. Ashley says that’s because his commanders wouldn’t give him time to do so. Madigan apparently wasn’t too concerned. “Patient is low-risk,” read a note in his file. “Case closed.”

After the press conference, reporters sidle up to Ashley. Scrappier than when the cameras were on, she acts like the kind of feisty blue-collar heroine Julia Roberts might play.

She tells a TV reporter about her attempts to get the military to hold a memorial service for Jared in addition to a funeral. An official, she relates, told her he understood her “concern.”

“I told them: ‘This isn’t a concern. It’s a demand. You meet it, or I’ll have the media knocking on your front door.’ “

After the reporters trickle out, she tells the guys at Coffee Strong—the antiwar coffeehouse run by veterans that is hosting the press conference—that she needs to feed 18-month-old Parker. She picks out a chocolate muffin from the pastry shelves and sits down with the toddler, who has been silently watching his mom. “Jared was the only one who could get him to talk,” she says as he nibbles.

We’ve arranged to talk more at her house, so she leads Parker to her black Chrysler, on the rear window of which is written “RIP Jared Hagemann: November 5, 1985–June 28, 2011” in block letters. She points the car southwest toward Yelm, a bucolic town about a half-hour away from the base. It’s a clear fall day, and the drive offers close-up views of Mount Rainier.

“On days like this, we used to go out into the woods and shoot,” she tells me upon arriving home to a rambler in a gated community popular with military families and dotted with American flags. Jared, she says, taught her how to use both his .45 pistol and then his .22 rifle.

Shortly after she enters the door, the phone rings. It’s 60 Minutes, eager to interview her for a program about PTSD. Word about her husband’s story has gotten out after an array of interviews with the local press and the progressive TV program Democracy Now, which took place after Ashley confronted Donald Rumsfeld. The former defense secretary was signing copies of his memoir at JBLM when the Army widow approached. She presented him with her husband’s funeral program and told the onetime hawk that her husband had gone to war because of his “lies.”

Now she puts off 60 Minutes until later and turns, embarrassed, to her living room. It’s cluttered with boxes, toys, and a diaper storage container, redolent of its contents. In the backyard, two dogs roam around knee-high weeds.

She seems annoyed by the mess, which she blames in part on a single mom she asked to move in to help her pay the bills. “I have no monthly income,” she explains. She did get life-insurance money from the military, but says she put it into a savings account for Parker and her 6-year-old son, Noah. It’s apparent, though, just how much she needs money now.

“Could you come back later?” she asks a Schwan’s driver when he pulls up with a grocery delivery, explaining that her roommate, who has food stamps, can pay when she gets home. “I got to work late anyway,” he amiably agrees.

Without the groceries, she and Parker tide themselves over for the afternoon with a bag of Frito-Lay party snacks. Noah, arriving home by school bus, fixes his own snack, putting a couple of hot dogs into the microwave and gobbling them down before heading out to play.

Then the phone rings again. This time it’s Noah’s school, reporting that the boy has been disruptive today. “Noah didn’t want to go to school,” Ashley explains to the administrator on the other end of the phone. Later she tells me why: The previous night she’d found her son sitting in the dark. “I miss Dad,” he said.

Ashley gets one final call before I leave for the afternoon. It’s from one of the Army investigators looking into Jared’s death. She steps into another room, but her voice carries into the living room. “I want everything wrapped up so I can heal and move with my kids,” she tells the investigator. “I don’t want to be around Fort Lewis anymore.”

Then she asks him something startling, something that hints at a whole other way of looking at her husband’s life and death. Has the investigator talked to the woman who’s going around saying Ashley was having an affair and had somebody murder Jared? “Obviously, that’s ridiculous,” she says quickly.

When Jared returned from Afghanistan in the spring of 2009, he told Madigan staff that he came home to “nothing.” He and Ashley had been separated for seven months. His wife had also recently accused him of attempted rape, a charge which police were now investigating.

It’s not the picture one expects, given Ashley’s outpouring of grief. Yet the Madigan records merely hint at the bitter and at times violent fighting between the couple. Ashley today insists she still loved her husband; she just couldn’t cope with the streak of violence he exhibited when he returned from war.

Whatever the truth, it’s not readily apparent from the extensive court and law-enforcement records that resulted from the couple’s discord. At times, even the authorities couldn’t figure out whom to believe. For instance, in the “attempted rape” case, Jared said he was a willing partner until he got out a condom, at which point she accused him of cheating on her.

Ashley’s story is dramatically different. She told Yelm police that Jared, who weeks earlier had moved into a separate apartment, had come over to drop off a check and started aggressively making advances. Although he ultimately left, she said she was scared of what he might do both to her and son Noah. “I know he has no problem with hurting people under 10,” she wrote in a statement, citing “what he had to do and deal with overseas.”

In a subsequent declaration to Thurston County Superior Court, Jared charged Ashley with using the allegations to coerce him into paying more child support. Those allegations were backed by her former boss, Robert Wright, who had supervised Ashley when she worked as an office manager for a furniture store. In a declaration, Wright wrote that Ashley told him “she would scream abuse and go to the military and she would get what she wants because he didn’t want to mess up his career.”

Nonetheless, a judge granted Ashley a temporary protection order against Jared. The police, in contrast, determined there wasn’t probable cause to arrest him. When an officer delivered the news, Ashley accused the cops of not “fucking doing anything” and threw the officer’s business card to the ground, according to his report.

That episode wasn’t nearly as dark as what came later. In June 2010, still married and living together again, the couple was fighting when Ashley screamed, according to an account Jared later told sheriff’s deputies: “You can’t satisfy me as a husband and your job is worthless!”

Jared “snapped,” he admitted to the deputies. He flipped the mattress over, grabbed her by the neck, and yelled that “what he does is important and he has had to see and do terrible things for both his country and their family!”

His wife complained about his job, he added to the deputies, yet she wouldn’t let him leave the Army because of the medical benefits. (That, of course, utterly contradicts what Ashley has said after his death, and she denies it.)

Jared told all this to the deputies a week later when they were summoned to the couple’s house by a 911 call, presumably from Ashley, reporting a suicide threat. The officers found Jared boozy but calm, and denying thoughts of suicide.

According to Jared’s account to police, he and his wife were both angry, and something he said set her off. “I wish you had died in the streets of Iraq, or would just kill yourself!” he said his wife yelled, and not for the first time.

Jared sat for a while, fuming. Then, he told the officers, he went upstairs to “prove a point.” He grabbed what he said was an unloaded rifle from the bedroom and tried to force the gun into Ashley’s hands.

“Is this what you want?” he asked his wife. “Since you want me dead, you should at least have some appreciation for what it’s like to pull the trigger yourself on another human being.”

In Ashley’s version of events, the gun was loaded and he was urging her to shoot him, saying he actually wanted to die. As for the ugly words she supposedly said, she says today that she had only once intimated that she wished he was dead, and that was years prior when in an alcoholic rage he had twisted her wrists and threatened her with a knife. “He never let me forget it,” she says.

Ashley’s mother says she thinks she understands why her daughter might have sometimes lashed out at her husband. “He would hurt her physically. She couldn’t do that. So she would use words.” Joppa says that she and her husband, who served in the first Gulf War, had the same dynamic when he was in the military.

PTSD doesn’t just affect the soldier, Joppa says. “It also affects the wives and the children. It tears them apart.”

That’s something researchers have been finding as well. In a May paper for the University of Southern California’s Center for Innovation and Research on Veterans and Military Families, two researchers noted a consistent—and possibly growing—correlation between PTSD and domestic violence. They cited one study that found that PTSD-afflicted veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan were approximately two to three times more likely to abuse their wives than were Vietnam vets with PTSD.

Preliminary results of another, ongoing study found that roughly 45 percent of veterans seeking treatment for PTSD had been aggressive with their spouses, who expressed fear of their husbands because of their wartime past. “I know he can kill,” one told the researchers. And the veterans, many of whom had weapons, conceded that they sometimes referred to their past in menacing ways: “I told her that if she kept on doing, arguing, and saying things that I didn’t appreciate . . . she will come up missing.” Ashley says Jared similarly threatened her. “I know how to commit the perfect murder,” she says he told her.

While there were times that law enforcement couldn’t sort out whether Jared really was abusive, and Ashley’s angry and erratic behavior with officers didn’t help her credibility, on at least one August night last year the evidence of violence was unmistakable. It was in the sink—a fistful of her hair that he had pulled out. Reeking of alcohol when the officers got there, he told them he had been going through his wife’s phone and found numbers that he didn’t recognize. He started questioning her and they fought, leading her (he said) to grab and scratch him, and him (they both said) to break down the pantry door in addition to going for her hair.

Over the past year or two, the military and the researchers who study it have attempted to figure out why soldiers are killing themselves. They have crunched statistics and pored over case files, according to Elspeth Ritchie, who until her retirement last year studied many of the files herself as a top psychiatrist in the Army’s Office of the Surgeon General.

The anguish of war, of course, is an obvious explanation, and it would seem that the more times soldiers go to war, the more distressed they might become. But, Ritchie says, “one of the things we’ve learned is that there’s no single explanation.” Rather, she says, there’s an interplay of factors.

Deployment is certainly a huge one, with roughly two-thirds of suicides occurring among soldiers who have gone overseas. And while a RAND Corporation report this year found “insufficient evidence” to conclude that multiple deployments lead to suicide, the report points out that repeated exposure to the battlefield can induce mental disorders, like PTSD, that are strongly associated with killing oneself.

Ritchie adds that researchers have found that the number of times a unit deploys, as opposed to a single individual, is also a predictor of suicide. With units that are constantly preparing for war, Ritchie says, commanders are moving too fast to notice red flags.

Multiple deployments can also induce another problem commonly seen in suicide case files: the loss of a relationship. For today’s soldiers, Ritchie explains, it’s not the same as it was during the Korean or Vietnam wars, where when you were home, you were home. With the military’s ranks stretched thin and soldiers racking up deployments like never before, “you know when you come home, you’re going to have to deploy again. You don’t reintegrate.”

Ritchie brings up another theme she’s repeatedly come across in suicide cases: “A soldier feels humiliated,” either by his commanders or by his spouse. Whichever, she says, “the military is a small place. So if you’re humiliated, everybody knows it.”

In Special Operations Forces, she continues, stressing that she knows nothing about Jared’s case, she has found that soldiers are particularly sensitive to losing face. “Members of special forces are very elite; you’re one of the club,” she says. “To make it, you have to go through special training. You wear a special patch. “

And for these soldiers, she says, the greatest shame can come from getting kicked out. That could well happen in the case of domestic violence or other criminal charges, she acknowledges. Or if you’re not asked to leave, you might be demoted. “In today’s Army, if you lose rank, you’re not going to get it back later on,” Ritchie says. The Army has become extremely competitive, with promotions boards more likely to pick soldiers with unblemished records.

Yet Jared’s military career looked—at first—like it might continue unscathed. After he was arrested for yanking out Ashley’s hair, he worked out a deal with the Thurston County Prosecutor’s Office that would have resulted in the charges being dropped after he completed a two-year “diversion” program. The court also imposed a “no contact” order until 2015 to separate him and his wife, according to prosecutors’ records.

But “we didn’t want it,” Ashley says. Despite the couple’s bitter battles, they were drawn to each other. “She always told me she didn’t know what she’d do without him,” says Ashley’s mother. Jared, during his 2009 breakdown, told Madigan staff that his primary goal was improving his relationship with his wife.

Set to deploy again in October 2010, he and his wife persuaded the court to let them communicate while they made arrangements. Three months later, in Afghanistan, he was promoted to staff sergeant. He re-enlisted that month.

Ashley says she was dead-set against it, but her husband cited the advantages. He would receive a $10,000 re-enlistment bonus, which could be used to replace one of the couple’s two broken-down cars. And according to Ashley, Jared’s commanders promised him that he would be put in a non-deployable position when he came home, and given six months off to go to school. She charges that the Army reneged on that agreement when he got back and was switched to a new unit, led by a commander who felt he needed the soldier overseas.

Brian DeSantis, a spokesperson for the 75th Ranger Regiment, to which Jared belonged, counters that Jared was offered a couple of non-deployable positions at Fort Benning in Georgia. “He turned them down,” DeSantis says. “He wanted to stay at Joint Base Lewis-McChord.”

In any case, Ashley concedes that her husband had another reason for staying: He couldn’t find a job worth leaving the military for. He had been looking, she says. But the recession was in full swing, and the only job he could get in the civilian world was at the very bottom.

Popular wisdom says that the military occupies a low rung on the economic ladder. Popular wisdom, however, is wrong. In an age of declining manufacturing jobs and an overall stagnant economy, the military offers some of the best pay available for people without college degrees. As a staff sergeant with dependents and seven years’ service, Jared would have received at least $53,000 a year from the Army, including a generous, tax-free housing allowance.

He would not have been the only one to feel trapped. The frustration felt by soldiers trying to leave the military—or support themselves once they do—is palpable at a job fair in late September at Camp Murray, the National Guard facility adjacent to JBLM.

Fifty-seven-year-old Wayne Fuller, bespectacled and uniformed, looks dejected as he threads his way through the lines of booths. There are an array of employers here—including PetSmart, REI, Union Pacific, the King County Sheriff’s Office, and Boeing—but the staff sergeant says he’s learned not to get his hopes up. He’s applied for more than 100 jobs since he got back from Afghanistan last year—his fifth tour in a military career that has spanned 24 years, most recently in the National Guard—but has had only two interviews, neither of which led to a job.

More depressing is the kind of jobs he’s seeing. “Eight to 10 dollars an hour, that’s about the norm anymore,” says Fuller. Last year, he says, the military paid him $75,000.

“We’re competing against guys who have four or six years of college,” says Angel Bermudez, a 20-year veteran and platoon sergeant who shows up at the fair in a dress shirt and neatly pressed pleated pants. He has only two years of advanced education, having studied criminology at a community college. At such a disadvantage, he says he’s applied fruitlessly for 1,000 jobs.

“It should count for more,” he says of a military background. He’s not just referring to the service soldiers have done for their country, though there is that—Bermudez has served six times overseas. He’s talking about the skills soldiers can offer to civilian employers. “You tell us what you want to do, we’ll do it. We don’t ask you why.”

Responding to rising levels of unemployment—veterans who have served since 9/11 are 30 percent more likely to be jobless than other Americans—this week President Obama announced a tax credit for companies that hire unemployed veterans. And there are employers who actively seek out soldiers. Union Pacific recruiter Derek Tompoles, manning a busy booth at the fair, says that people in the military are a good fit for the railroad company because they are adept at physical labor and are used to working outside both day and night. But there simply aren’t enough jobs to go around. As an example, Tompoles cites a track laborer position that pays roughly $40,000 a year. For each opening, he says, the company receives 300 to 500 resumes.

In June of this year, Jared faced the consequences of sticking with the Army: He was to go back overseas in two months. This time, according to Ashley and her mother, he seemed unable to rally himself. Switching to a new unit—bereft of the buddies who had made Iraq and Afghanistan feel like home and, as Ashley portrays it, led by an unsympathetic commander—had been a blow. He had held a gun to his head at least three times, according to Ashley.

“He kept saying he couldn’t do it anymore,” recalls Joppa. “He was done.”

He apparently also feared coming home once again to “nothing.”

“He was afraid that Ashley was going to leave him,” Joppa says. “I tried to reassure him. But he said, no, he wasn’t going to go overseas. If anybody came after him, he was going to take as many of them down with him as he could.”

DeSantis insists Jared never expressed these sentiments to his superiors. The Rangers’ spokesperson says he talked to Jared’s battalion commander in the firestorm after the soldier’s death. “Brian, he never asked not to deploy,” he says the commander told him.

On Father’s Day, Jared seemed in better form. He took his family to Great Wolf Lodge, the water-park resort south of Olympia. Although the no-contact order was still in effect, and he was officially living at the barracks, he saw his family frequently.

But the following Friday, as Ashley tells the story, he became irate. He called her on her cell phone while she was driving back from the base, where she had been getting permit stickers for her car. She told her husband she couldn’t talk.

When she got home, she found that he had suspended her cell-phone account. Without another phone, she went to her mother’s house to call Jared. They fought, then she and her mom fought. Joppa doesn’t remember the details, but guesses she said something like “You guys need to pull yourself together,” which she had been saying for some time. “War does ugly things to people,” she’d tell her daughter. “We can’t understand because we’re not over there.”

Joppa says she went to do something, and “all of a sudden,” her daughter was gone. Ashley left without taking the kids or telling them she was leaving. Then Noah disappeared, prompting Joppa to call 911. When the boy turned up at a nearby park, he said he had gone looking for his mother.

Ashley, on the other hand, did not reappear so quickly. Joppa called Jared to let him know. That night, the soldier showed up at Joppa’s door and told her he wanted to take the kids to his parents’ house in California. Joppa hesitated. “But I decided, ‘Well, with all the stuff going on around here, maybe it’s best.’ “

“He was really emotional,” Joppa recalls. “He kissed my cheek, and thanked me for everything I had done to help the kids and Ashley. It was almost like a good-bye. I thought, ‘Oh you know, he’s just upset.’ I brushed it off.” Jared delivered the children to his parents, who at his request had driven north to get them.

The next day, Joppa called 911 to report her daughter missing and—ironically, given what came later—possibly suicidal. “Told her friends that she wants it all to end and she doesn’t want her children anymore,” reads the 911 report.

“I never said that,” insists Ashley, blaming the mischaracterization on a former friend. “I said that I wanted it all to stop. I didn’t want to live like that anymore.”

She describes her disappearance by saying she needed time away to think. “I didn’t know where I was going to go.” She considered the ocean, she says, then went to stay with a high-school friend.

Jared, meanwhile, was calling friends, neighbors, and Child Protective Services to tell them that his wife had abandoned the children and was having an affair, according to Ashley. Sometimes, she says, he would pretend to be a detective.

On Sunday she returned to her mother’s house. She was livid, as she would tell a sheriff’s deputy that day, that her husband had “stolen” the children. The deputy called Jared. “Jared was not willing to work with me when I asked for his assistance in returning the children,” he wrote in his report. The soldier was also “upset” and “aware that he could be facing criminal charges.”

His military career, whether he wanted it or not, was once again threatened.

Maybe it was in that phone call that Jared announced he was going to “blow his head off.” It’s not clear from the police records, but Ashley and her mom say such an exchange occurred. The two women and the deputy were at Joppa’s house. Joppa spoke to Jared first. “He was screaming,” she says, and he told her he was holding a .350 Magnum to his head.

Joppa handed the phone to the deputy, something she later came to regret. “There was no compassion,” she says. By her and her daughter’s account, the deputy told the deranged soldier to “man up.”

Ashley filed for her last protection order the next day, Monday. “I was afraid he was going to come after me,” she says. But Jared couldn’t be served. By Tuesday, he was dead.