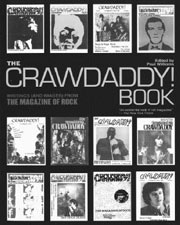

THE CRAWDADDY! BOOK

WRITINGS (AND IMAGES) FROM THE MAGAZINE OF ROCK

edited by Paul Williams

(Hal Leonard, $18.95)

‘Twasn’t always thus, the media-industry lockstep, the two-thumbs-up/Siskel & Ebert brand of music journalism we’ve become so accustomed to. Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away—Philadelphia’s Swarthmore College, circa 1966 to be exact . . .

“I was bored in my first semester at college,” writes Paul Williams in the introduction to The Crawdaddy! Book: Writings (and Images) From the Magazine of Rock, a 320-page anthology of the first 19 issues of Williams’ 1966-68 rock ‘zine Crawdaddy!, Williams outlines how, as a music buff impressed by such scholarly magazines of the era as Sing Out! and Downbeat, he wondered why rock didn’t have an equivalent. “One day in late January 1966 I was in a drugstore off-campus looking at a fan magazine aimed at teenage girls. I read that two of my favorite bands, the Yardbirds and the Rolling Stones, had got their start playing in the Crawdaddy Club—and it hit me in a blinding flash that it was now time to start this rock ‘n’ roll magazine I’d been thinking about, and that it should be called Crawdaddy!.“

Williams, of course, had no inkling that his brainstorm would alter the face of rock journalism. As he puts it in his book, he simply wanted to engage a dialogue: “[These] new rock ‘n’ roll groups and records [were] what was happening in our lives, and the idea of a magazine where this music would be talked about seriously was like a proclamation of the existence of a community that was already there, waiting to be acknowledged, waiting for a place to talk with one another about it all.” Between semesters, Williams wrote up a handful of reviews (including a lengthy appreciation of Simon & Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence) and a statement-of-purpose editorial entitled “Get Off of My Cloud” (“This is not a service magazine [such as Billboard]. . . . We are trying to appeal to people interested in rock ‘n’ roll . . . “). Far more time-consuming than putting HTML text up on a Web site, Williams remembers every labor-intensive minute of it.

“Yes,” says Williams now. “First I’d do a lot of listening to records, then write about them—and ask others to write, too. Then type up everything on mimeograph stencils, using a typewriter with the ribbon removed, after making headings and designing some kind of simple cover. Starting with [the fifth issue], the magazine was offset printed at a print shop. So it was a matter of typing and pasting up clean, camera-ready copy, and then lots of work addressing and mailing ’em.”

In his 2001 book In Their Own Write: Adventures in the Music Press, British author Paul Gorman spoke to a number of sources able to illustrate precisely what Williams’ magazine brought to the table:

Lenny Kaye: “For me, Crawdaddy! was a revelation, because it was the first time I’d seen writing about this music with some depth. It wasn’t just favorite likes/dislikes . . . they took music writing to a level which matched the creativity of the works they analyzed.”

Jim Derogatis: “Williams wrote about the music he loved in essays that were like letters to his friends, and before long his hand-stapled fanzine began to attract other aspiring rock critics. . . .”

Richard Meltzer: “Pieces that I wrote with musical content started getting published. . . . It made the most sense to write about what was still rather meaningful and magnificent. In the process, I—along with two or three others— essentially invented the rock-write genre.”

Bold words, Dick. But Meltzer’s dead-on. Even yours truly, as a teenage record collector stuck away in a tiny Mayberry of a southern town, was deeply influenced by Crawdaddy! and its subsequent spawn—classic rags like Fusion, Creem, Phonograph Record Magazine, even the early incarnation of Rolling Stone, whose founder/publisher, Jann Wenner, picked Williams’ brain prior to launching RS in ’67.

Williams today is somewhat matter-of-fact about his magazine’s milestones, pointing out how, initially, “the music biz had trouble taking us seriously the first year because they’d never seen such a thing before. Getting review copies of 45s was a challenge, [but] Elektra and Columbia Records were cooperative. Being a penniless teenager was a primary obstacle to getting things done, but teenage pluck, hitchhiking everywhere, sleeping on floors, living on peanut butter sandwiches, helped a lot.”

Starting to get advertising from national record companies after meeting Elektra’s Jac Holzman at the Newport Folk Fest was a breakthrough. “It meant a lot to get California distributors and feel like a national mag. And of course finding someone else to do regular writing, someone who knew more about music than I did—Jon Landau, Sandy Pearlman, Richard Meltzer, and Linda Eastman as staff photographer.”

Williams downplays the journalistic strides he and his staff made. Issue No. 5 brilliantly juxtaposed back-to-back interviews with the Animals’ Eric Burdon and blues giant Howlin’ Wolf. Issue No. 7 contained a complex analysis of Indian raga music in rock by future Blue Oyster Cult/Clash producer Pearlman. Meltzer’s now-infamous “The Aesthetics of Rock” graduated from offbeat college thesis to full-blown subversive journalism in issue No. 8, and he followed that up the next issue with the equally dizzying “The Stones, the Beatles and Spyder Turner’s Raunch Epistemology.” (I didn’t know what an “epistemology” was, but it sure sounded cool rolling off my tongue in junior high English class.) And the hits just kept coming, from exclusive interviews with underground musicians to exhaustive, thousands-of-words-in-length think pieces.

One such review sprung from Williams’ pen early on, in issue No. 4, a dissection of Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde album. Williams had already been encouraged by no less than Paul Simon (who personally rang up to thank him for the Simon & Garfunkel review) and Dylan himself (impressed by the magazine’s first two issues, he invited Williams over to his hotel). The Blonde on Blonde review, Williams suggests, was his breakthrough as a writer.

“The album meant so much to me right away that it was a big challenge to reach deep enough into myself to feel I was even beginning to say something true and meaningful about this wonderful music and our community of listeners’ personal and collective relationship with this artist,” recalls Williams. “There was a poetry in the language of this essay that satisfied me and pointed me towards all the writing about music and other topics I’ve done since. I was finding my voice, indeed, and I just felt different about this piece of writing, even though of course it still seemed very imperfect and inadequate to me. A door was opened inside me.”

Just the same, by the tail end of ’68, after taking circulation from 500 to 45,000 in just 19 issues, Williams had had enough. Hassles in his personal life, coupled with business-induced professional burnout, convinced him it was time to put his child up for adoption. Crawdaddy! soldiered on under a series of different publishers until 1979. For his part, Williams joined a commune in Mendocino, hung out with such cultural icons as Philip K. Dick, Timothy Leary, and John and Yoko, and subsequently authored his own books on Dylan, Brian Wilson, and Neil Young.

Williams doesn’t regret having given up the vehicle that put his name on the map—in fact, he revived Crawdaddy! as a mail- order quarterly in 1993 (consult www.cdaddy.com for details)—although to hear him tell it, the life of a maverick writer can be a financially shaky one.

“To tell the truth, I am right now looking for a job after somehow supporting myself and families as a writer and self-publisher all these years. I don’t regret my independent path, but with a small baby and huge debts, at age 54 I’m finally acknowledging what most everyone else knows and accepts, that it’s not easy to make a living as a writer or any kind of ‘artist’ and there’s a lot to be said for steady work and pay,” says Williams. “It’s a scary fork in the road but I’m sure it’ll work out well. But yeah, walking away in late ’68, though it was very hard to do, was the right step for me, in hindsight. I don’t regret following my heart, and I’m pleased with the life of meaningful work that’s resulted.

“However, I’m unhappily currently wrestling with letting go of the new incarnation of Crawdaddy! because I find I can’t afford this particular labor of love in terms of time and money. As in 1968, it’s taken me close to a year of internal wrangling to arrive at my decision. It now seems very likely I’ll let Crawdaddy! go again.”

Say it ain’t so, Paul! Do yourselves a favor, gentle readers, and go pick up The Crawdaddy! Book. And relive the words and visions—the heart, the mind, the soul—of a genuine revolution.