RUGBY, ENGLAND, SPRING ’87: Four scruffy twentysomethings are sprawled across secondhand bed mattresses arranged at asymmetrical angles on the floor of VHF Studios. The smoke from their roll-ups and spliffs gets so thick that the engineer routinely disconnects the facility’s smoke alarm prior to each day’s session, which can range from intensely focused overdubbing to jam-until-the-tape-runs-out free-for-alls to simply lying around in candlelit darkness and passing comment on playbacks of the previous day’s work. Ultimately, from this near-womblike setting will emerge one of the greatest psychedelic albums of all time.

“Dope and then some!” is how former Spacemen 3 guitarist Pete “Sonic Boom” Kember characterizes the making of The Perfect Prescription. According to Kember, he, fellow guitarist Jason Pierce, drummer Rosco, and bassist Pete Bassman were seeking the same spiritual and musical liberation as their heroesthe Velvets, Stooges, MC5, Suicide, 13th Floor Elevators, Red Krayola, etc.and certainly on a chemical level as well. “We had mattresses for the best possible recording and playback positioning,” he recalls, “and some days we would just get blitzed and spend a day just listeningin situ, so to speak. Think of it like the testing done before releasing a new drugha ha!”

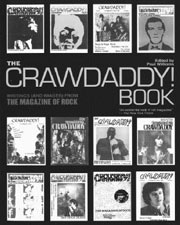

I’ve just dropped in to see what condition Kember’s prescription is in, the occasion being a two-CD collection of Perfect Rx demos, outtakes, and alternate mixes titled Forged Prescriptions (Space Age Recordings). The set has been long in coming, having weathered a nearly seven-year series of contractual delayswhich wouldn’t necessarily be of significance, except for the fact that Perfect Rx itself, an album that’s been hailed by the likes of Sonic Youth and Mudhoney and a critics’ mainstay of desert-island-discs lists, has come to cast a long, legendary shadow over the years.

PERFECT PRESCRIPTION went virtually unnoticed, particularly by the British press, when it first appeared in August of ’87, on tiny U.K. indie Glass. An ad hoc fraternity of psych aficionados and fanzine writers took note, however, and while that fraternity is frequently prone to hyperbole and indiscrimination, this time around, the aesthetic and cultural significance of a recording became a matter of near-universal underground accord. One need not be reminded of the Velvet Underground Effectone great album begets a hundred bands, who in turn beget a thousand more bandsto understand how time, opinion, and recorded artifacts have a funny way of eventually aligning.

A concept record that aurally chronicles the highs, lows, and heavenly blows of a virtual drug trip, Perfect Rx is (to quote from one of my own reviews) “an unqualified masterpiece of shimmering, beatific melodies, rhythmic/dynamic tension, and stylistic contrasts.” More florid but just as accurate are these comments from the liner notes of the first CD edition (1989, Fire), labeling S3 revolutionary artists in the tradition of Bo Diddley, the Rolling Stones, Arthur Parker, and Paul Gauguin and calling the album “an untrumpeted classic, an arcane, apocryphal document . . . telegraphing a message of unconcerned hope in a world hypnotized by guilt-ridden social-work rock.” Indeed, whether fueled by hemp, adrenaline, or other substances, the band expertly channeled full-bore garage shock (“Take Me to the Other Side”) alongside proto-ambient dronescapery (“Ecstasy Symphony”), additionally taking time to pay ace tribute to Lou Reed (“Ode to Street Hassle”) and the Red Krayola (“Transparent Radiation”).

Recalling how the social climate of 1987 was overwhelmingly Thatcherite/ Reaganite repressive, Kember suggests that Spacemen 3’s agenda was benevolently subversive: “We felt there would be other people who felt like us out there, people who lived their lives like usthe antithesis of the yuppie. Certainly, we hoped the renaissance that was washing in on a wave of ecstasy would be fertile ground for us. Religion, drugs, and sexual taboos were all areas that needed some comment from a more liberal source than was mostly heard back then.”

Forged Prescriptions, then, represents a vital glimpse behind the Perfect Rx curtain. Notable is a tune like “Walkin’ With Jesus,” which on the first album was dreamy and minimalist but now has additional guitar tracksfeedback, tremolo, etc.newly restored. Apparently, a number of tunes had been shorn of excess guitar in order to help ease the material’s transition to the stage. (“Jason was in favor of more complex arrangements,” says Kember, “but ultimately agreed we didn’t need it for the songs to work well.”) Another track, “Ecstasy Symphony,” originally served as a languid intro for “Transparent Radiation”; it’s now a nine-minute hissing/droning instrumental with a much hotter mix. In fact, the entire first disc of Forged Prescriptions, with the alternate versions and a different song sequence from the parent album, represents, says Kember, “a ‘could also have been’ situation,” who adds that he likes the material “at least as much [as], if not more [than],” that of Perfect Rx.

Disc 2 is also a treat for S3-heads, featuring demo recordings of album songs as well as three unreleased tunes: a rollicking, groove-laden Velvet Underground homage titled, helpfully, “Velvet Jam,” plus two coversa churning, wah-wah-filled take of the MC5’s “I Want You Right Now” and a surprisingly tender, dreamy interpretation of Roky Erickson’s pre-13th Floor Elevators outfit the Spades’ “We Sell Soul.”

Worth noting for fans, too, is the Forged Prescriptions artwork: It diligently reproduces the psychedelic spirals motifs and text font design that graced the sleeve of Perfect Rx, adding an alternate picture of Kember and Pierce taken at the original album photo session.

THE EIGHT-YEAR TENURE of Spacemen 3 has always been viewed from the outside as a fragile alliance between Kember and Pierce. To a degree that’s true, although Kember is quick to point out that while S3’s creative mojo was in maximum tumescence during the making of Perfect Rx, cracks in the group’s foundation began appearing shortly thereafter: “They [Rosco and Bassman] were always less committed to it than Jason and myself, and they weren’t prepared to put in the practice and effort needed. They also ran away with themselves on tour, getting too drunk to play well, etc.” As a revolving cast of additional players began infiltrating the S3 universe, Kember and Pierce gradually grew apart to such a degree that sessions for the fourth and final studio album, 1990’s Recurring, were attended separately by the two songwriters. The two haven’t spoken directly since the early ’90s, and Kember, the proud keeper of the S3 flame, now regards the situation with regret.

“There was a healthy collaboration and competition between us to deliver the goods,” admits Kember. “Mainly for ourselves, but also for those we hoped would find it useful in their lives. I hope I’m big enough to sideline my feelings about what happened at the end of Spacemen 3, and Jason’s role in that, and to give him credit he is due for this. His songwriting, his singing, his guitar and other instruments please me as much now as they did then. I’m very sad that we seem unable to communicate. I’ve heard no comment from Jason about [Forged Prescriptions], and it was my project in that sensehe isn’t interested in seeing that side of Spacemen 3 maintained. He is very hard, by his choice, to contact, and that’s his choice, fair enough. I do feel that I lost a great musical partner and friend. Along with the destruction of the band, it was pretty devastating to me. It’s a very large part of my life, not just something I do for kicks as an aside.”

Pierce, of course, went on to much success with Spiritualized. For his part, Kember has kept busy with an array of frequently overlapping projects, most notably the ambient/electronic Experimental Audio Research and the comparatively more straightforward Spectrum. The latter, in fact, toured across America in 2001, with set lists heavily weighted toward old S3 tunes. Kember hopes to repeat that trek later this year once the new Spectrum album is completed. He indicates he’s been working with Randall Nieman, guitar whiz for Detroit-area experimental-psych combo Fuxa, and that the material is shaping up along guitar/bass/drums/organ lines not dissimilar to vintage S3. (Kember also traveled to Los Angeles recently to work with electronic-rock artist Alex Gordon for a projected EP to be titled Dead Man, due this fall.)

Meanwhile, there’s a possibility that further archival offerings from the S3 vaults will be exhumed. A couple of years ago, Space Age reissued the group’s third album, 1989’s Playing With Fire, featuring a bonus disc of session demos, and Kember notes that he has a lot of live tapes, in particular “some early live stuff that is pretty devastating which might see light one day.”

But even if the world had never again heard from the Rugby players, we’d still have their timeless gem in our hands. It’s often said that groups can’t possibly set out to paint their masterpieces, that only hindsight can be the true arbiter in such matters. Just the same . . .

“We felt we were doing something different,” insists Kember solemnly, “and we were very proud of it. We knew it was what we were aiming for.”