In a year of dramatic social turmoil, few would have predicted that two of the most political statements emerging out of hip-hop would come from Jadakiss (“Why?”) and Eminem (“Mosh”). Where once were clenched fists are mostly just iced-out rings despite heated polemics by dead prez, Immortal Technique, and others. Notably quiet amidst it all were two rappers many fans expected to see on the front line: Talib Kweli and Mos Def, the duo formerly known as Black Star.

When they first mapped onto the public consciousness as solo artists in the mid-’90s—prerecession, pre-Dubya, pre-9/11—high on their task list was taking on hip-hop’s declining social relevancy. As Kweli’s biting B-side “Manifesto” put it, “If you rhyming for the loot/You’s a prostitute.” Beyond critiquing rap’s increasing materialism, the two also offered insightful, progressive commentary. Songs from 1998’s Mos Def and Talib Kweli Are Black Star, like “Thieves in the Night” and “Respiration,” addressed the deleterious effects of the crack wars and urban neglect at a time when many other rappers romanticized or sensationalized nihilism.

Since then, the two have gone on to separately release five albums; their newest CDs appeared two weeks apart. Kweli has been more prolific but has struggled musically to balance commercial appeal and social engagement. The two are not mutually exclusive, as Kweli well knows—his biggest hit, from 2002’s solo debut, Quality, was “Get By,” a sparkling, soulful street anthem dedi-cated in part to “the blacks and Latins in prison. . . . We missin’ you, the love is unconditional.” Kweli surprised many when he invited Jay-Z to do a guest verse on the song’s remix; later, Jay-Z paid tribute to him on The Black Album‘s “Moment of Clarity”: “If skills sold, truthfully/Lyrically, I’d be Talib Kweli.”

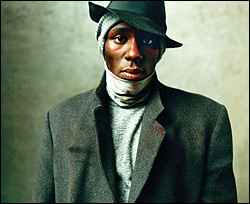

Conventional wisdom says that this was Kweli’s kiss of death, setting up impossibly high standards for his next project. However, Kweli’s new The Beautiful Struggle (Rawkus) is neither brazenly ambitious nor stolidly conservative—mostly it’s just tepid. The production carries at least half the burden here: Any of the beats are instantly forgettable, veering from the tinny electro-rock of “We Got the Beat” to the snoozy “We Know” and, worst of all, “Around the Way,” which interpolates the Police’s “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic,” to maximum schlock effect.

As for Kweli, he lacks a commanding voice but his conversational flow has an appealing familiarity. That’s what made “Get By,” and such new songs as “Black Girl Pain” and “Ghetto Snow,” effective—they speak with people and not just at them. Alas, his braggadocio isn’t nearly as engaging. The Beautiful Struggle fails to rouse the crowd, especially with such calculated, formulaic fare as “Back Up Offa Me,” “Broken Glass,” and “A Game.” It’s a demure, safe album; despite delivering its share of pleasures, it’s often innocuous to the point of blandness. Kweli still seems unsure of his direction, caught between the club stage and a soapbox—even though peers like Kanye West and Jay-Z have stepped on both with little issue.

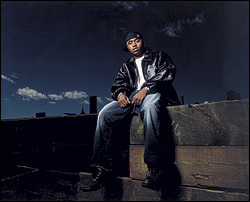

IRONICALLY, IF KWELI stifles The Beautiful Struggle by being too market conscious, Mos Def’s The New Danger (Geffen) suffers by not engaging populist sentiment enough. Credit Mos with an unabashedly ambitious album that mixes blues, rock, and soul with a smattering of actual rap songs. It’s tempting to compare The New Danger with Andre 3000’s The Love Below: Both are self-indulgent, eclectic works that challenge conventional notions of hip-hop. However, The Love Below took its aesthetic cues from pop with loud, shiny songs powered on catchy hooks and Andre’s relentless energy.

By comparison, Mos Def is downright laconic, with no real urgency to get through a weighty 18-track playlist. If not for more tightly composed songs like the sly, stylish “Sunshine” and the incisive “Close Edge” (“I’m the catalogue, you the same song”), The New Danger would sound less like an album and more like one long jam session that departs into noodling soul tunes (“The Panties”), dubbed-out rock-strumentals (“Freaky Black Greetings”), and repetitive blues riffs (“Blue Black Jack”).

Mos Def is laudably provocative and innovative here, but what The New Danger lacks is heat: that amorphous quality that inspires listeners to yell out lyrics and launch hands skyward. Excepting the sparse, funky “Grown Man Business” and thick rolls of “Ghetto Rock,” The New Danger is cool to the touch, almost dispassionate.

Especially in a year as wrought with sound and fury as 2004, this would have seemed an opportune time for these two artists to make their voices heard as loud and strong as possible. Instead, they take on too much and too little, respectively, effectively easing any outrage from a scream to a whisper.