Stop—the Chinks took over the game.

—Jin, “Learn Chinese”

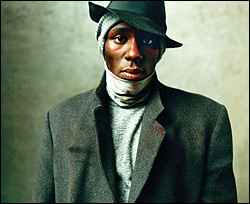

An Asian American recorded the first rap song. So says Joe Bataan, the Latin soul singer and self-described “Afro-Filipino,” who asserts that his 1979 single, “Rap-O, Clap-O,” was completed months before the Fatback Band’s “King Tim III,” released the same year, which is acknowledged as hip-hop’s first recording. According to Bataan, no label would gamble on releasing “Rap-O, Clap-O” until after “Rapper’s Delight” blew up later in 1979.

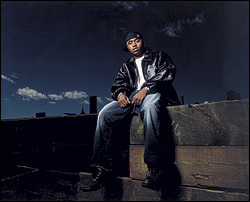

Whoever came first, 2004 marks recorded hip-hop’s 25th anniversary, and it’s fitting that a quarter- century after “Rap-O, Clap-O,” rapper Jin Auyeung has crossed another milestone, becoming the first Asian Pacific Islander (API) MC to release a hip-hop album on a major label when Virgin issued The Rest Is History in mid-October.

The quick-witted rapper made his initial mark by destroying seven straight weeks of competition on BET’s 106 and Park “Freestyle Fridays”; soon after, he was invited to join the Ruff Ryders, the crew that includes Jadakiss and Eve. Magazine stories soon chronicled Jin’s personal history: His parents immigrated to Miami—and later New York—from Hong Kong, and Jin was involved in a Chinatown gang shooting. As his career climbed via his lyrical bootstraps, Jin’s life embodied a familiar American narrative. As Jeff Chang put it in the SF Bay Guardian, “Forget The Joy Luck Club. Through dropping rhymes in the clubs, Jin had rewritten the Asian-American dream.”

Throughout, race has been Jin’s double-edged sword. His Asian heritage has helped pique media curiosity from XXL to NPR, but it’s been as much burden as benefit. Jin is expected to be an ethnic trailblazer, but in a field so invested in a culture of blackness, being Asian creates an unavoidable crisis of authenticity. This is nothing new—nonblack hip-hop artists have always faced extra scrutiny. Earlier generations of white MCs tackled this dilemma by either masking their whiteness behind convincing displays of black style (3rd Bass), marketing themselves to alt-rock audiences (Beastie Boys), or avoiding black fans entirely. API rappers have toyed with similar tactics: The first major wave in the early ’90s aligned with the pro-black politics of the era. Public Enemy–inspired groups like the Bay Area’s Asiatic Apostles, New Jersey’s Yellow Peril, and Seattle’s Seoul Brothers pumped a Yellow Fist in solidarity. By the mid-’90s, such respected underground artists as L.A.’s Key Kool and Philadelphia’s Mountain Brothers switched strategies, playing down race and pumping up skills, championing an “it’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at” mantra.

Credit Eminem with the paradigm by becoming the first white MC to appeal to both the hard-core hip-hop audience and the malls. 2002’s “White America” openly acknowledged how his whiteness has served him as a selling point. Eminem neutralized naysayers from making an issue out of his race by striking first. Jin astutely followed that preemptive strategy on his lead single, “Learn Chinese,” opening with the challenge, “Yeah, I’m Chinese—and what?”

This is Jin’s first word on ethnicity; thankfully, it’s not his last. If his racial difference is inescapable, Jin wisely chooses to embrace it. Plenty of rappers brag about their cross- racial conquests, but on “Love Story,” Jin raps about the backlash he endured for dating a black woman: “Imagine having to choose between the one that you love or your fam/That’s like cutting off your right or left hand, damn.” On “Same Cry,” Jin appeals to hip-hop’s humanism, articulating the struggles facing immigrants here and people abroad, from the SARS epidemic to Nike’s labor practices. It’s not all love, though. For “Cold Outside,” Jin slaps back at his API detractors: “What hurts is all the bullshit comes from my own kind/They say, ‘Jin’s fake, he don’t keep it real in his rhymes.'”

This underlying tension gives The Rest Is History a heft that, on conventional lyrical craft and sonic force alone, it frankly doesn’t have. His freestyle roots serve him well on anthems like “Here Now,” but as a love paean like “Senorita” demonstrates, he’s not as polished a songwriter as he is a battler. Nor is his storytelling skill convincing on the narrative “The Good, the Bad, the Ugly.” History‘s production is surprisingly tepid, too—despite contributions from Kanye West, Just Blaze, and Wyclef Jean, only the blaring brass on “Handz Off” leaves an impression.

History scores mostly on content as it coheres around its topical thread. Though ethnicity gives Jin a center, he’s not playing the race card—”I know that it’s been debated/I’m a gimmick they created,” as he puts it in “C’mon.” It’s hard enough to be a new artist without also shouldering the expectations of all the API MCs waiting to step through the door that Jin is prying open. If it took 25 years from “Rap-O, Clap-O” for this opportunity to materialize, Jin’s embrace of race and reality should ensure that it won’t take nearly that long to happen again.