For their role in creating some of the first really commercially and aesthetically successful examples of what synthesizer-based pop music could sound like, and their subsequent inspiration to the people who developed Euro-disco, technopop, electro, house, and techno, people now speak of Kraftwerk’s influence on contemporary music as being Ramones-size, even Beatles-size. Yet when they rearrived on the music scene with their first real album since 1986 (and only their second real album since 1981, not counting a 1991 remix album), last year’s Tour de France Soundtracks (Astralwerks), the musical context Kraftwerk helped create was so used to living without them that it was ready to swallow them whole with barely an audible gulp. It’s true the album and assorted singles have been hits in Europe, and their international tour is doing quite nicely. But there’s still been the faint whiff of anticlimax at the band’s return as recording artists, especially when people discovered the creators of bloody-minded beat workouts like “Numbers” and “Musique Non-Stop” had grounded their new single, “Tour de France ’03,” with whispering vocals and an equally unobtrusive beat. It seemed as if they had finally come back after lo these many years, only to not try very hard.

But Kraftwerk have always made a show of modesty and subtlety that can easily be mistaken for noninvolvement. Kraftwerk first arrived as an international force when they scored a fluke hit with “Autobahn” in 1974. The song was a lovely impression of driving a car very fast into a horizonless future; buoyed by the whooshing and humming of then-novel synthesizers, it sounded like the endless forward momentum of American rock and roll after it was streamlined into the perfect efficiency of perpetual-motion machines. After gently mocking the dozing concertgoers of a contemporary Kraftwerk performance in Detroit (imagine that happening now), Lester Bangs recognized that “Autobahn”‘s representation of pure driving excitement showed that “the ultimate power is exercised calmly.” Perhaps in recognition of the fact that the twin activities of blissing out and boogeying down have been in strategic alliance since the beginning of music, you could still find tranquil undercurrents throughout Kraftwerk’s records even as their music became more and more beat-driven. Even their most headlong foray into the world of rhythm, 1981’s “Numbers,” is guided into silence by the wistful corniness of “Computer World 2,” which concludes it.

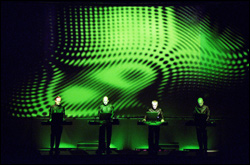

This modest approach has proven to be one of the most enduring aspects of Kraftwerk’s cultural presence. If their politely robotic persona—matching suits, affectless voices, static stage presence–suggested to some the final stages of dehumanization back in the ’70s, today it seems like benevolent camp, or a goofily serious version of the tech boffinism that rules so many quarters of contemporary culture. One can even modulate that camp into outright humor without doing injustice to Kraftwerk, as Craig Robinson does on his delightfully twee flipflopflyin.com Web site, where a pixelated cartoon of the band circa 1978’s The Man-Machine studiously stands still, day in and day out, at Kling-Klang studios—though sometimes they indulge in the occasional cancan.

Tour de France Soundtracks never actually becomes quite that funny (unless the fussy ostinatos all over “Vitamin” count, and they might), but Kraftwerk’s modesty can still overwhelm. What initially seems so timid about the suite of the new “Tour de France” tracks (they come in three etapes—that’s the French term for the stages of a bicycle race—book-ended by a prologue and “Chrono,” which carries most of the musical themes of the etapes to a conclusion) becomes, in its own quietly determined way, as sensational as an endorphin high. As hard as this critic may resist them, the most obvious bicycling metaphors invariably come to mind. Like a seasoned athlete who knows how to pace himself while riding through uneven terrain, this music comes on as a series of peaks and troughs: Some bits are more harsh and minimal, other bits blissfully driven by the thumping solidity of a piano lick straight from a classic house-music track being sublimated dubwise into blossoms of quicksilver mist, all the time guided by that softly persistent needle-on-vinyl beat.

For the remainder of the album, Kraftwerk take the time to catch their breath. Things are slower overall, and familiar Kraftwerkian tropes are repeated. “Vitamin” runs through a laundry list of nutrients, “Elektro Kardiogramm” skanks along rather serviceably, and by the time “La Forme” comes along, its shuffle of intoned “-tion” words gets tiresome, being neither slow enough to be atmospheric and touching nor fast enough to pump the blood. Its endless endless length (close to 10 minutes with reprise) appears to function as a way to give the consumer nearly an hour of music, reminiscent of another way Kraftwerk are trying to catch up to their colleagues—amazingly, since 1986’s Electric Cafe only lasted a measly 36 minutes, this marks the first time they’ve ever tried to make a real CD–length album! Arriving at the tail end of Soundtracks, “La Forme” has the unfortunate effect of causing the album to feel more entropic than it actually is, an impression that makes the album-closing appearance of the perkier original 1983 “Tour de France,” never one of Kraftwerk’s great ones, actually quite welcome.

The original was, in may ways, the last gasp of the band before a long spell of hermetic inactivity, blamed in part by sympathetic observers on Kraftwerk’s difficulty in adapting to the mad rush of technological and musical advances in the ’80s . . . and, ironically, in part due to Ralf Hutter’s near-fatal bicycle accident not long after the single’s original release. Taken in that light, “Tour de France” seems to be both a bid to symbolically return to the point just before everything went wrong and defy their mortality, both as creative individuals and as human beings. (The health- and exercise-related themes of this album are unsurprising obsessions for prosperous children of the ’60s as they inch closer to the great inevitable.) Soundtracks is hardly great Kraftwerk, but it’s still intriguing, even poignant, if only because you can tease out of it a soft-spoken concession from Ralf und Florian that, yes, they really are quite human, even if they are robots.

Kraftwerk play the Paramount Theatre at 8 p.m. Mon., April 26. $31.50.