Starting at age 5, I had a crazy fascination with the states of the union. Like any kid that young, I was begging for all kinds of stimulation, and here were these mystic toy-glyphs begging for decryption: a mess of straight lines interrupted by haywire squiggles, names that were gurgles of letters with no reference to any words I knew, places that established the existence of a world outside. Within weeks of my initial interest, I could rattle the states off in alphabetical order. That tackled, I wanted to actually visit these places, and pored over atlas after atlas to plot the perfect cross- country route. This, of course, was mooncalf ridiculous. I was nowhere near the driving age, and even for an adult with a car, it’d still be ridiculous, costly, and time-consuming—just too big an idea for a kid to contemplate.

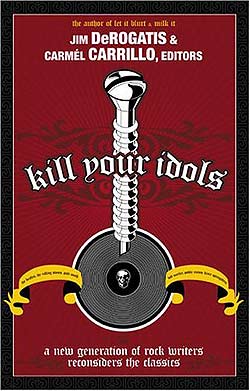

So of course I’m going to love the shit out of Sufjan Stevens’ Illinoise (Asthmatic Kitty), or the idea, anyway. Stevens’ plan to make a record for every state in the U.S. is as overambitious as anything a precocious kid would dream up, and his second entry in the series is a formal match for that extravagance.

Stevens’ first entry was a look back to his childhood home of Michigan, filled with quiet songs about the people who, like him and his family, lived on the margins of society. Illinoise‘s characters live in vans and have no heat in the winter, but the subject matter largely unmoors Stevens from firsthand experience and instead finds him contemplating a galaxy of almanac facts. Like a kid’s 50-state book, TBS’s Portrait of America specials from the ’80s, or Rick Smolan’s 24/7 coffee-table book series, Illinoise is a grand, corny gesture toward painting the essence of a state with the broadest of strokes. Stevens respects both the megafuckopolis of Chicago and the wee village of Birds, ponders the Columbian Exposition of 1893, gets a visit from Carl Sandburg in a dream, and remembers Satchmo and Gacy and Douglas and Lincoln and Lincoln’s wife. The references to stuff like the Chickenmobile and Octave Chanute might even leave Illinoisans feeling like strangers to their own state.

This may make Stevens sound like an insufferable show-off—the musical equivalent of a McSweeney’s writer a little too self- regarding about his command of the mundane, or, for that matter, a 5-year-old who can recite all 50 states in alphabetical order. Hearing him wax ecstatic over tourist traps or give yet another interstitial track a 30-word title with too many exclamation marks won’t help. But one of the things that saves Illinoise from falling victim to a chronic case of the formalist cutes is Stevens’ musical austerity. Its tracks are built upon solo piano, banjo, and acoustic guitar; even when it veers toward chamber pop with female choruses, it veers toward Steve Reich–style minimalism. (Michigan had this, too, though admittedly it’s a touch fruitier here.)

The other saving grace is the way in which those encyclopedic facts of Illinois become raw material for Stevens’ metaphors and stories of God’s work in the world. This is in seeming contrast to Stevens’ 2004 album, Seven Swans, a dramatization of a love of God shown, not shouted, even when the subjects were resurrection and tribulation. The subjects of Michigan and Illinoise are ostensibly secular. But I doubt someone as deeply devout as Stevens can dwell on man and his works for very long without seeing God’s presence in them. He is there as Stevens sings of the young friend he prays for as she dies from cancer, of the runners on the underground railroad who’ve “got a better life coming,” of humble Decatur as “The Great I Am.” He is there as several songs blur together the patriotic declarations of a state song and the Blakean visionary: “Peoria! Destroyia! Infinity! Divinity!” He is even there when Stevens muses upon John Wayne Gacy and the boys he hacked up and concludes, “I am really just like him.” The declaration carries maybe a smidgen of vanity with it, as if Stevens is trying to show off just how far he can abase himself in the eyes of the Lord. Yet it also suggests the moral equality amongst all men and women in the state of original sin.

“I can’t explain the state that I’m in,” Stevens sings on gorgeous “The Predatory Wasp of the Palisades Is Out to Get Us!”—his voice later cracking high and free at every third line above pulses of waltz-time horns and woodwinds that seem to grow and grow. It is tempting to describe this as a story of male-male agape—just touching on the erotic, with mentions of falling asleep in the backseat of a car—between Stevens and his best friend, but Stevens also lets you see right through it as a love story between himself and Jesus, God born human, a man stung and mocked and wrestled with. We may see ourselves as the members of a state or a country. There may be a kind of equality in a state of sin. But we are brought to an even greater unity when we love Jesus, who brings us into the highest relationship with God. Yet, in echoes of the narrator’s ecstasy, the chorus is left gasping inarticulately over the “great sights upon this state! Hallelu!/Wonders bright, and rivers, lake.” Stevens loves the country in much the same way he loves people: He senses the infinitude of God in both, and it sets him reeling.

Sufjan Stevens plays the Triple Door with Liz Jones at 8 p.m. Fri., July 22–Sat., July 23. $15.