Johnny, as former operating room nurse Sarah Blum describes him, was a red-haired, blue eyed, freckled young man about 20 years old, healthy and strong.

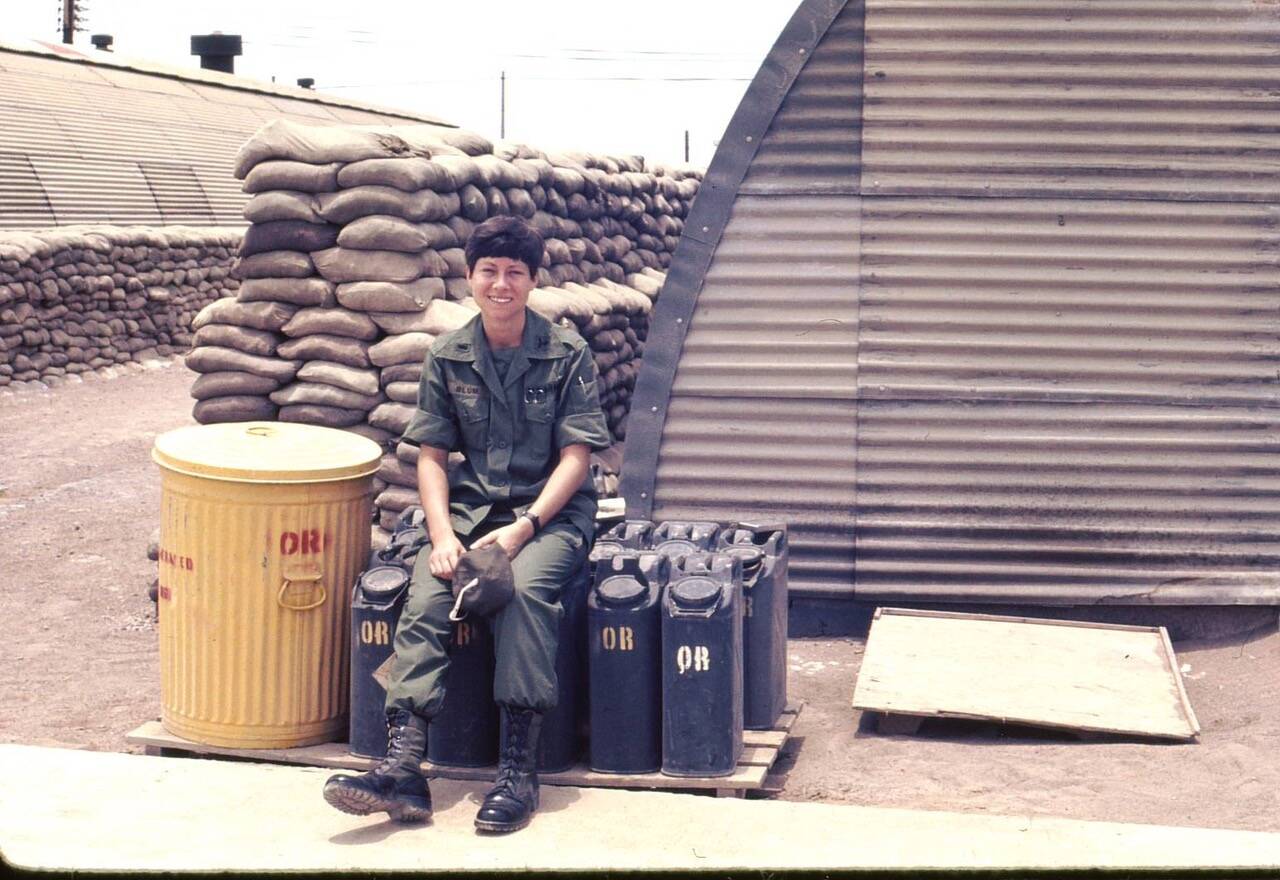

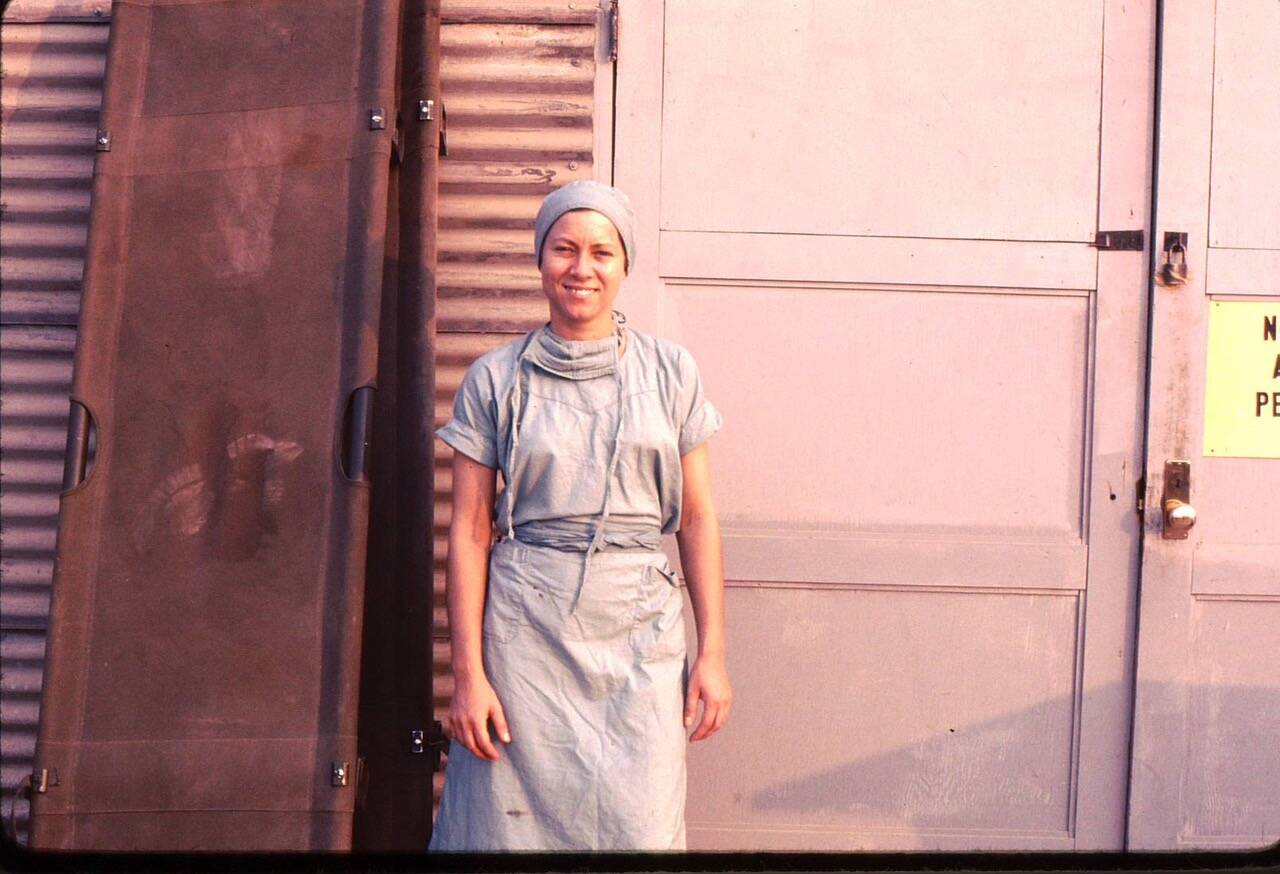

But that’s not how he reached Blum and the other nurses and doctors in the operating room of the 12th Evacuation Hospital in Cu Chi Vietnam one hot, humid day in 1967.

“He had been hit by American artillery and his whole body from his hips down, was just thoroughly blasted open, black, ugly,” Blum recalled. “We had to take his legs off, everything to his hips. You don’t see that here in everyday life. It was horrific.”

It haunts Blum.

But back then, for the sake of all the wounded she tended, she couldn’t allow her emotions to get the better of her.

“I couldn’t show my feelings over there,” the Auburn resident explained. “If I did, the casualties that would come in, they would read my face and think it meant they were going to die. So I had to learn to shut it all down.”

As she was to find out years later, separating her body and emotions from what she was seeing was to have profound consequences on her life.

The Vietnam war ended for Blum in January 1968, when her year-long tour was up. She returned to the United States and got on with her life. She attended Seattle University until 1970, the year she married a fellow Vietnam vet. In 1971, the couple had their first child, a daughter, and in 1975, a son. Today she is a retired nurse psychotherapist.

“My whole world was my family back then,” Blum said.

She suspects the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was present when she returned to the U.S., although it wasn’t until the early 1980s that she become aware of it.

“I had some flashbacks,” she said.

When the PTSD first manifested, it would be on an ordinary day, as she was on her morning commute on I-5 to the clinic in Tacoma where she worked.

At one moment, she said, she saw soldiers in “an ordinary army truck” in the left lane. In the next, the army truck, the traffic and the day disappeared. Once again, she was the 26-year-old operating nurse she’d been, waiting in a blood stained Quonset-hut-operating room in Cu Chi, the arrival of yet another load of bloody, pale and wounded young men.

“I was seeing the dirty, blackened faces of casualties, blood, bandages, the whole thing,” said Blum. “Their eyes were just pleading.”

Her sense of disorientation was total.

“I was shaking, it shook my world. But I was on I-5 and driving. I had to to pull over to the side of the highway. I cancelled my appointments that day. I didn’t think I was in any shape,” Blum said.

She didn’t understand what had happened to her, didn’t know much about PTSD, and certainly didn’t know it would be the first of many post-traumatic stress induced flashbacks that would upend her life from then on.

Another one hit her in February 1984, again while she was on the road.

“It had snowed a little bit, and the road was a little slippery that day, but I was doing fine driving, when all of a sudden I saw this white truck. It was fishtailing, so I moved over, because I didn’t want to be close to it. After I moved over, it slid into the guardrail …and in my flashback it was an army vehicle that had exploded. It wasn’t really happening, but that’s what I saw,” Blum said.

Writing it all down

The parts of herself that Blum had to close off to help those young men during the war had her attention, and would take decades of therapy to fully open back up.

Reconnecting has been helped by her participation in a number of art and writing programs tailored for veterans, among them, recently, “Path with Art” in Seattle and “Red Badge,” a writing class.

“I have been writing a lot about the different stories, which has actually helped. It’s better that it’s out rather than stuck in there, rolling around.”

Blum has set it all down in “Warrior Nurse: PTSD and Healing,” a 288-page manuscript she hopes to see published. Part memoir, part narrative-non-fiction, it revisits her experiences in Vietnam, what happened to her afterward when she began to show signs of PTSD, the process she went through to heal herself, and then learning about PTSD as a professional psychotherapist.

It would be her second book. The first, published in 2013, was “Women Under Fire: Abuse in the military,” a searing examination of sexual abuse in the armed forces.

Her memoir starts on the day she arrived in Vietnam to serve in the chaotic, frenzied operating room of the 12th Evacuation Hospital. In the telling, she lays out all she had to deal with in 1967 and afterward, including her inner conflicts.

”Everything was strange and different,” Blum said of her first days in the country. “I had no way to relate to so many things. Like just going to the 90th Replacement Battalion. We had this little building that we stayed in with bunk beds. Rats running around. I wasn’t used to that,” Blum said

Even at 26, Blum said, she was one of the older nurses, but “very naive.” She said most of the nurses were closer to 21 or 23 and the soldiers were 19 or 20.

She had been assigned to the 71st Evacuation Hospital at Pleiku when she was on her way to Vietnam. But the hospital had not been built yet, so the head nurse in Vietnam changed her assignment to the hospital at Qin Yan, setting of the 80s television series “China Beach.”

“It was mostly a civilian hospital. I was not very happy about that because I went over there to serve, so it just didn’t seem right,” Blum said.

Later, the head nurse switched her assignment with that of another young nurse, who’d been visibly terrified at the prospect of going to Cu Chi. Blum went to Cu Chi and the other nurse to Qin Yang.

The 12th Evac hospital was set on a desolate plane in the infamous Iron Triangle, known for the ferocity of the fighting there. All the operations were there, so the battlefield was everywhere around. On any given day, units like the Wolfhounds, the Manchu or the Bobcats would be hit badly, and the 12th would get the mass casualties in.

When Blum returned to the United States in 1968, she found her country at war with itself — young people burning their draft cards, marching in the streets, torching American flags.

“It was difficult and painful,” Blum said. “I didn’t know where I fit in. I wasn’t a civilian, I wasn’t one of them, and they were angry at those of us who’d been to Vietnam. So I didn’t want to tell anyone who I was. Here I’d been to war. I I knew what that was, but this was different. One time a protester attacked me with eggs and spat at me. I didn’t feel safe at home.”

She describes PTSD, what it is, how it affects people, how it manifests differently in different people, how it affects the brain and body, and then identifies resources that could help the sufferer with the healing process without having to attend therapy or a group.

Later, she relates her experiences in Washington, D.C., where she went for the Salute to Vietnam Veterans. There she testified at the first PTSD hearings ever, at the very first hearing on Agent Orange, and the “tremendous emotion” that poured out of her fellow veterans. She also took time to visit the Vietnam War Memorial.

“When we tell our stories is when it all comes alive again. But I never know from one moment to the next what’s going to come up. Only when the emotions come up now, I let ‘em. I don’t want to ever close them again,” Blum said.