You know how you get a craving for sushi and sometimes default to whatever’s closest—and maybe whatever offers a happy hour—even though it’s mediocre? (No judgement—I do it too.) Well, two hours spent at the sushi counter at Wataru in Ravenna (2400 N.E. 56th St., 525-2073) may forever spoil that decision of convenience.

Chef Kotaro Kumita, who studied under Seattle’s legendary Shiro Kashiba, has perhaps surpassed the master, and that is something truly rare and marvelous to behold. Though there is some seating at tables, where diners can choose between two sushi sets as well as individual pieces, the real raison d’etre here is the six-person seating at the counter (one at 5:30, another at 7:30) for an omakase dinner (chef’s choice), where you’re fed until you’re full—which translates to about 20 pieces of fish and other delicacies from the sea if you go the whole mile. Omakase is available at plenty of sushi restaurants, but Wataru employs the Edo style (from the Edo era of Japan: the early 1600s to the mid-1800s, when the shogunate held power over even the emperor). The sushi of that time was characterized by its sourcing (directly from Tokyo Bay) and by its methods of preservation before refrigeration existed, using ingredients like kelp, straw, vinegar, and bamboo leaves to marinate or sterilize the fish and prevent it from spoiling.

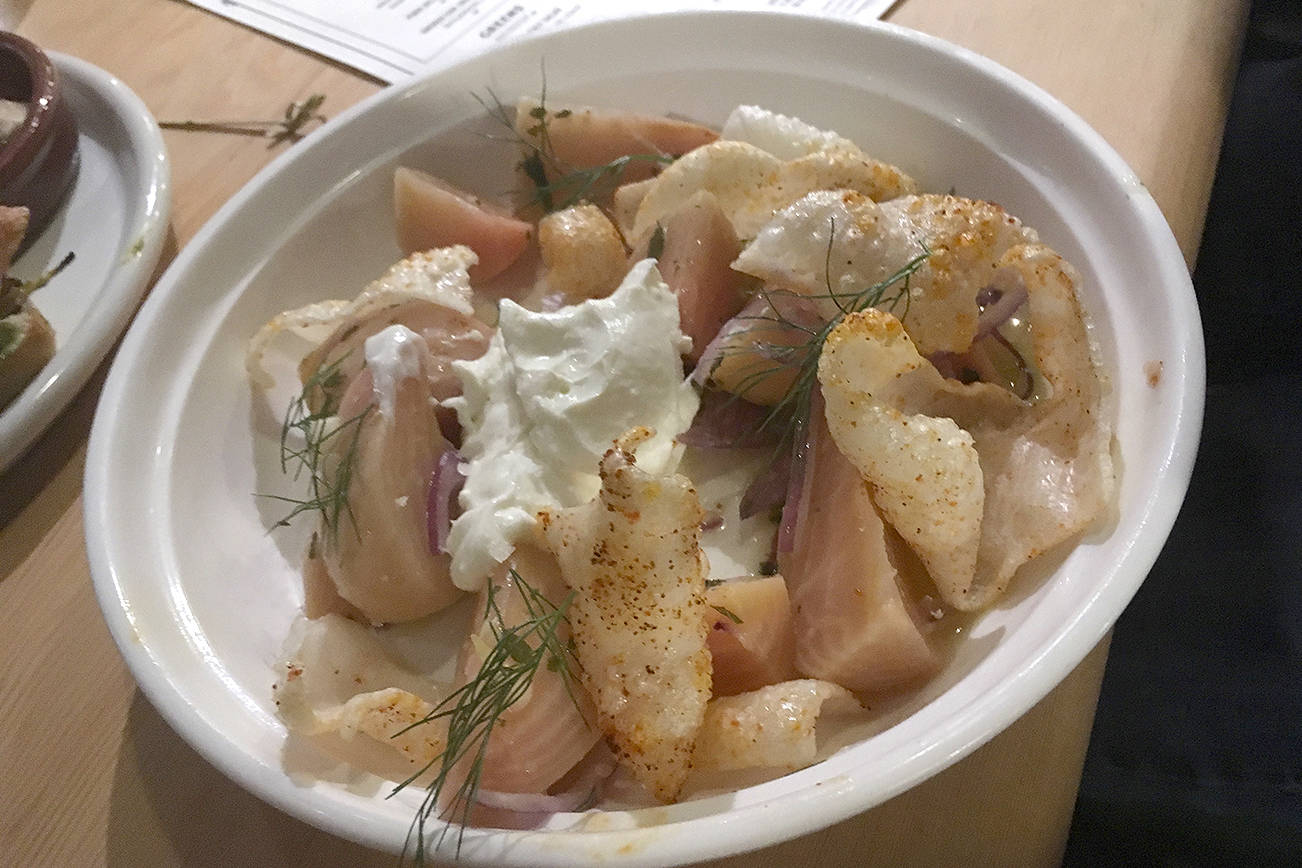

At Wataru, the ethos behind the Edo style—serving whatever is currently in season and at its freshest, be it from Puget Sound or flown in from a particular region of Japan—is integral. There are scallops from Hokkaido, red snapper belly and barracuda from Kyushu, Washington king salmon belly and albacore, and Maine crab. And not only the fish is remarkable, so are the techniques Kumita employs to bring out their fullest, authentic expression: Amber jack from Japan is nestled in kelp for several hours and, when served, imparts a beautiful mouthfeel with just a hint of fat; red snapper is lightly seared, and thus served with the skin partially on. Sockeye belly gets a touch of onion, shiso leaf, and ponzu jelly—the acidity meeting the fat head on, the palate reveling in a little explosion of tartness from the ponzu. A scallop gets touched for a second with the flesh of a lemon and sprinkled with Okinawa salt, and Kumita suggests eating it in one bite. Raw scallop is one of my least favorite sushi items and I never order it, but I follow the chef’s humble order and I’m instantly converted. There’s nothing slimy or chewy about it; it’s slick and sweet, and the kiss of the lemon is a fleeting moment of gentle citrus on the tongue.

As he talks—explaining the provenance of a fish, answering questions—his hands never stop moving, briskly pulling fish from light wooden boxes before cutting and searing and seasoning. The boxes, he tells us, allow the fish to stay at room temperature before being served, which maximizes the flavor. We are given no wasabi or soy sauce, which masks an ingredient’s true nature. Instead we put our trust in Kumita’s competent, magical hands and knowledge, and allow him to decide which fish get which treatment—for example, a black snapper that’s smoked in rice straw at a low temperature to prevent burning, which yields a smoky sweetness you’d never expect to find from an aquatic creature.

I marvel at not just the exquisiteness of the food itself, but the chef’s quiet yet authoritative and friendly nature; he manages to turn the evening into both a reverie and a lively education. While over at Sushi Kashiba there’s the magnificent view and a bit of showmanship among the half-dozen chefs, at Wataru there is little to distract from Kumita and his practiced skill, and only one chef assists him. The room is small, with blonde wood, light colors, and a few well-placed plants and art. Both your eye and your mind are consumed by what lies in front of you: the food.

We learn that the amount of time a fish marinates in kelp depends on how quickly it absorbs the flavor, which in turn depends on its fat content—so blue tuna from Spain takes two hours compared to 20 minutes for albacore. We discover zuki style, which involves a quick sear followed by a 20-minute marinade in kelp, soy, and sake. We try a part of the fish between the belly and the butt, the tima—medium-fatty with a buttery quality that slowly dissolves into the tongue’s warmth. We are treated to buri, which the chef says is the largest of all the yellowtail tuna, and, finally, as the meal winds down, to sea eel (which in Japan is never served alongside freshwater eel) and uni (always green, not purple, which can be bitter). The two uni aficionados in our little group of six have been waiting patiently for it all night. I have always been a bit of an uni skeptic—not adverse to it, as some are, but simply underwhelmed. But in this lovely bite—one of the only pieces of the evening that comes wrapped in nori—I finally understand why many liken it to a taste of the freshest essence of seawater. I hold its aqueous flavor and soft texture in my mouth a little longer than usual.

The meal ends simply, appropriately, with a slightly sweet tiny egg omelet (tamago) followed by a super-tiny, palate-cleansing burdock root and octopus with shiso leaf that sends us off into the dark night, our bellies full but far from uncomfortable. We’re at once calm and enlivened, like the perfectly balanced pieces of sushi themselves.

food@seattleweekly.com