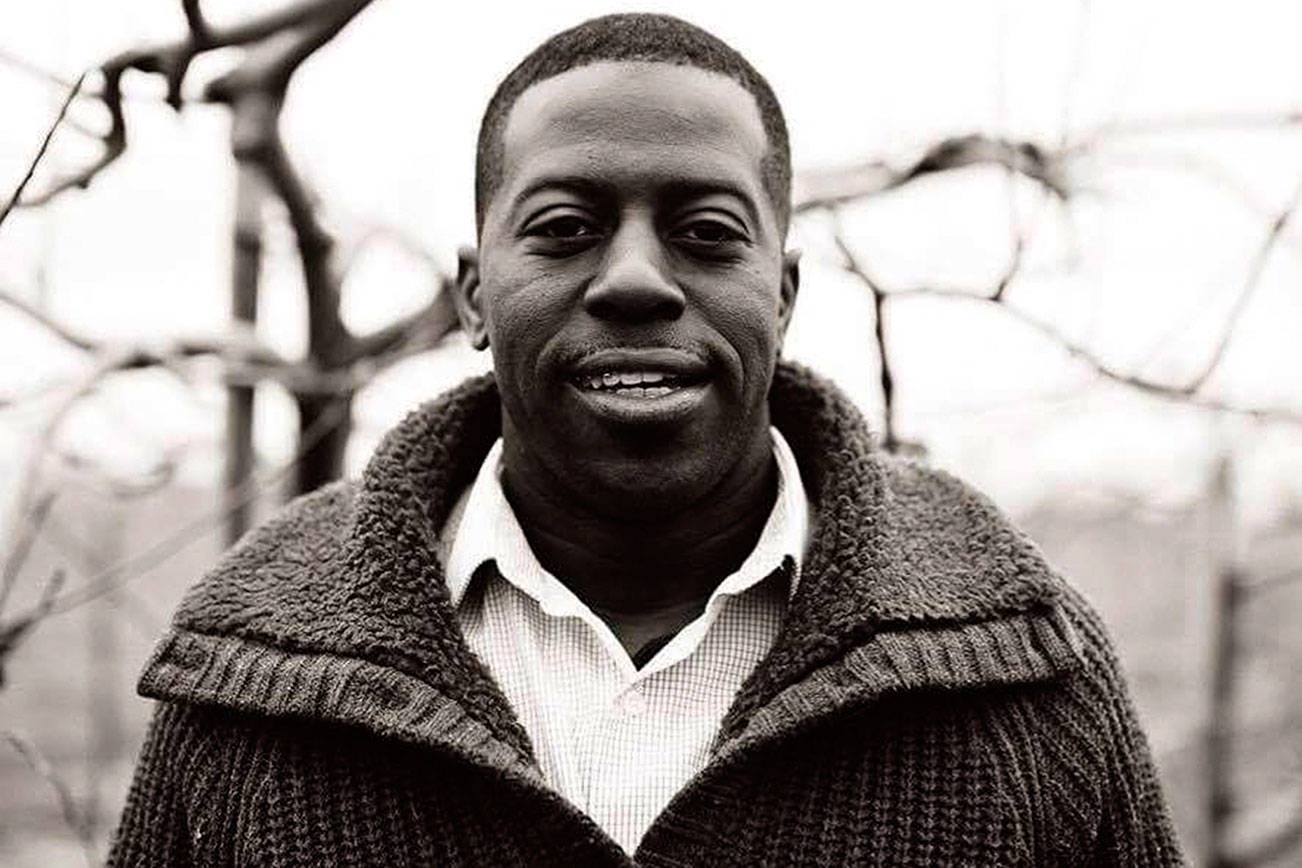

When chef Edouardo Jordan encounters something, he examines it thoroughly. For the Seattle-based restaurateur,winner of two prestigious James Beard Foundation Awards (Best Chef Northwest and Best New Restaurant for JuneBaby), nothing important is taken at face value. Rather, Jordan is interested in a thing’s origin and what it might be used for in the future, whether traditionally or untraditionally. Which is why, when he decides to celebrate and highlight Black History Month in his trio of stellar restaurants, it means something both flavorful and educational.

This month, Jordan has planned a series of events for his Ravenna neighborhood eateries—Salare, JuneBaby, and Lucinda Grain Bar—that include guests, classic dishes, and history lessons. To highlight the month, Jordan has invited South Carolina chef B.J. Dennis (Feb. 9 at JuneBaby), former Top Chef contestant Carla Hall (Feb. 16 at JuneBaby), Woodinville-based brewer Rodney Hines (Feb. 17 at Salare), and acclaimed author Dr. Jessica B. Harris (March 2 at Salare) to provide lessons on the history and future of black cuisine in America. “It’s important that we take a moment to celebrate the culinary history that African Americans and Africans have played in this country,” explains Jordan, who attended culinary school in Florida and later moved to Seattle to open his first restaurant, Salare. “I want to be on the forefront of bringing it to light, especially here in Seattle, because it can get looked over.”

To kick off the month, FareStart, a local nonprofit that offers culinary employment opportunities to homeless and disadvantaged people in Seattle, is showcasing and serving one of Jordan’s signature dishes—Creole chicken with black rice, Swiss chard, and fried plantains—at its Boren Avenue Maslow’s location. And when February concludes, Jordan says he plans to make a personal exodus to Nigeria to explore and learn more about the country’s culinary impact. “In case you haven’t noticed, I’m a chef of color,” Jordan says. “Being that I have a bigger voice in the industry today, it’s important to use that voice wisely. As adults, we get caught up in our daily lives—we go out to eat and we don’t think about how food has influenced us as a culture, a community, and a society. I wanted to make sure we took a moment to stop and think about all of that.”

When Jordan talks about the history of cuisine, especially about black chefs, the word “diaspora” quickly comes up. The term has a deep impact on Jordan’s culinary way of thinking. Many black lineages in America can be traced back to violent migrations from Africa, and other more modern lineages, like Jordan’s, include traveling from places far and wide to new cities like Seattle. In those journeys, Jordan says, much can change in a recipe or story. Keeping track of those histories becomes an essential exercise for the thorough-minded.

For Jordan, honest representation in the kitchen is key. In Seattle, a strong and well-respected group of black chefs are making waves in the restaurant scene: Feed the People’s Tarik Abdullah, Luvn Kitchn’s Unika Noiel, That Brown Girl Cooks’ Kristi Brown, Plum’s Makini Howell. But while this group indicates culinary progress, there is more to be done to diversify positions of power in restaurants. “I pray that we as a group can influence the diversity of the Seattle culinary scene,” Jordan explains. “Young culinary students have the opportunity to look to us for examples, which is something I didn’t have where I came from.”

When thinking about social progress and culinary role models, it’s impossible not to think of Jordan’s young son, to whom the chef dedicated his James Beard Awards in his recent acceptance speech. For Jordan, food is a way to bond over an experience and to teach his son about the beauty of excellence, leadership, and creativity. In many ways the education the chef pours into his son’s creative mind is a microcosm for how he looks at his role as an educator in the city and world at large. “Food has always been part of my life,” says Jordan. “It’s what keeps me grounded and centered. So the dinners that my son and I have together are about sharing moments and understanding history. My son gets to know about things like chitlins before I ever got to learn about them. He gets to know the true history of their why and what and where it all came from.”

For someone who worked his way from culinary school to the top of the culinary food chain, Jordan knows the importance of education and fortitude. While he’s not one for excuses, he’ll tell you it’s not easy to be a black chef in America. Opportunities and expectations are different for him than for his white counterparts. Nevertheless, all that he’s worked for and all his successes come as no surprise to the driven entrepreneur. “I wouldn’t have done all this if I didn’t think it was possible,” he says. “You have to set goals, you have to have standards. Those standards can be different for everyone—and I set mine very high. I know I can achieve anything I want to do. If I decided I wanted to be an astronaut 20 years from now, I’m going to be a damn astronaut and I’m going to walk on the moon!”

And while 2018 marked an almost impossible rise to culinary fame for Jordan, he says has no intention to let that year be the only high point in his still-burgeoning career. “I try not to dwell on 2018,” Jordan admits, “because 2019 is a whole new year. If anything, 2018 is just a megaphone for 2019, a platform for more people to see us do what we do well. I don’t dwell on last year because we have new and different and hopefully even better things to do this year.”