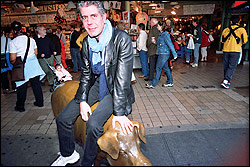

Anthony Bourdain had been working in professional kitchens for more than 20 years when his scandalous memoir, Kitchen Confidential, was published in 2000. But so extravagant was the tone of those “adventures in the culinary underbelly,” so apparent Bourdain’s desire to play the role of a dirty-mouthed, no-bullshit tough guy, that even a reader disposed to believe every squalid little secret of the New York restaurant world could be forgiven for wondering if ol’ Tony was all that hot a chef himself. Suspicions deepened when his next public outing was a grand tour of culinary exotica for the Food Network, which revealed Bourdain to be even mouthier than he came off on the page, given to wearing sleeveless camouflage tees to expose his sticklike arms and the teensy barbed-wire tat round one skinny biceps. All mouth and no muscle was the general conclusion.

Now comes Bourdain’s first actual cookbook, Anthony Bourdain’s Les Halles Cookbook (Bloomsbury, $34.95), named for the downtown New York brasserie where Bourdain has served as executive chef since 1998. At first glance, the book seems like more of the Bourdain same. Though on the cover his name appears 10 times as large as those of Les Halles owners José de Meirelles and Philippe Lajaunie, Bourdain admits in the introduction that many if not most of the recipes in the book were on the menu long before he arrived and derive from a tradition of unpretentious working-class cooking whose roots are lost in the urban French past.

Then there is the overall tone of the prose. No one would expect Bourdain, with his rep, to adopt conventional cookbook language, but still, I think it will be a shock to most readers to find themselves addressed variously as “num-nuts,” “dick-head,” and “dip-shit,” as well as like endearments sprinkled erratically throughout the book. Even if you are not put off by these, you may bridle at assertions like, “Les Halles . . . [is] the best, the most authentic frog pond in the whole damn U.S. of A.,” or, “Anyone who says ‘cooking is in the blood’ when talking about professionals is talking out of their ass.”

For a cook experienced in traditional brasserie cuisine, the recipes don’t look like anything special. Like all restaurants of its traditional kind, Les Halles is a place for people who have no issues with meat—or butter or cream or kidneys or whole fish with the heads on. The Les Halles Cookbook caters to the same appetites: people who agree with Bourdain when he says, “I don’t care if it makes me glow in the dark, or causes the occasional tumor in lab rats, as long as it tastes really, really good.”

The recipe lineup is so trad, in fact, that I might have overlooked the book’s saving grace if a friend who doesn’t mind a little kitchen cussin’ for a good cause hadn’t pointed it out. “Bourdain is full of little tips—like ‘let the veal bones brown but not blacken’—that other books simply gloss over,” he said. “At times, it’s like he’s looking over your shoulder and actually teaching you instead of saying, ‘Here’s a recipe, now go make a mess of it.'” And it’s true. Nearly every dish throws out some special and necessary information: “careful with the salt, buckaroo” in the cod casserole brandade de morue; “heavy duty food-processor” for the lobster bisque (“Any doubts about yours, move on to another recipe”); even plain comforting afterthoughts (on rillettes: “Jesus, this dish is easy. Don’t tell your friends. Let them think you’re a genius . . . “).

When you start ignoring Bourdain’s braying tone and begin listening to what he’s saying, you realize that the man really loves the food he writes about, loves cooking, and wants you to cook and to love it as much as he does. And his general notes on organizing a kitchen and a meal contain pure behavioral gold for even experienced home cooks. His pages alone on the art of mise en place—”the meez,” as he endearingly calls it—will make a better, more relaxed, more sensitive cook of you. Against all odds, this culinary loudmouth is a better teacher than most.