In August, McDonald’s announced some big news: The fast-food giant plans to overhaul almost half its menu in light of consumer demands for healthier food. Sandwich buns will be made with sugar instead of high-fructose corn syrup, artificial preservatives will be eliminated from Chicken McNuggets, pork sausage patties, and eggs, and only antibiotic-free chickens will be used. The news shouldn’t be surprising considering that the fast-food behemoth has been on a decline for the past three years, according to CNN Money, with drops as high as 30 percent in year-to-year sales and deteriorating earnings for shareholders.

While several factors are behind the plunge, the biggest is customer unhappiness regarding the actual food—as admitted by the company’s CEO—with many people, particularly younger consumers, seeking alternatives like Panera and Chipotle over McDonald’s and other long-standing chains like Taco Bell and Pizza Hut. Not only are the products arguably better-tasting at these so-called “fast-casual” establishments, but they’re healthier and have fewer artificial ingredients.

The farm-to-table movement has gained momentum over the past 10 years, but until recently it has been the provenance of the elite, available mainly at upscale, pricier restaurants. Now, particularly in urban areas like New York, San Francisco, and Seattle, the movement’s underlying ethos has finally trickled down to convenience food. Mindful sourcing is increasingly important to diners, even when they’re just grabbing a burger and fries—and the parents who eat at the high-end restaurants want that same kind of sensibility when they take their kid out for chicken tenders. It’s a huge win: quality combined with fast-food service and prices.

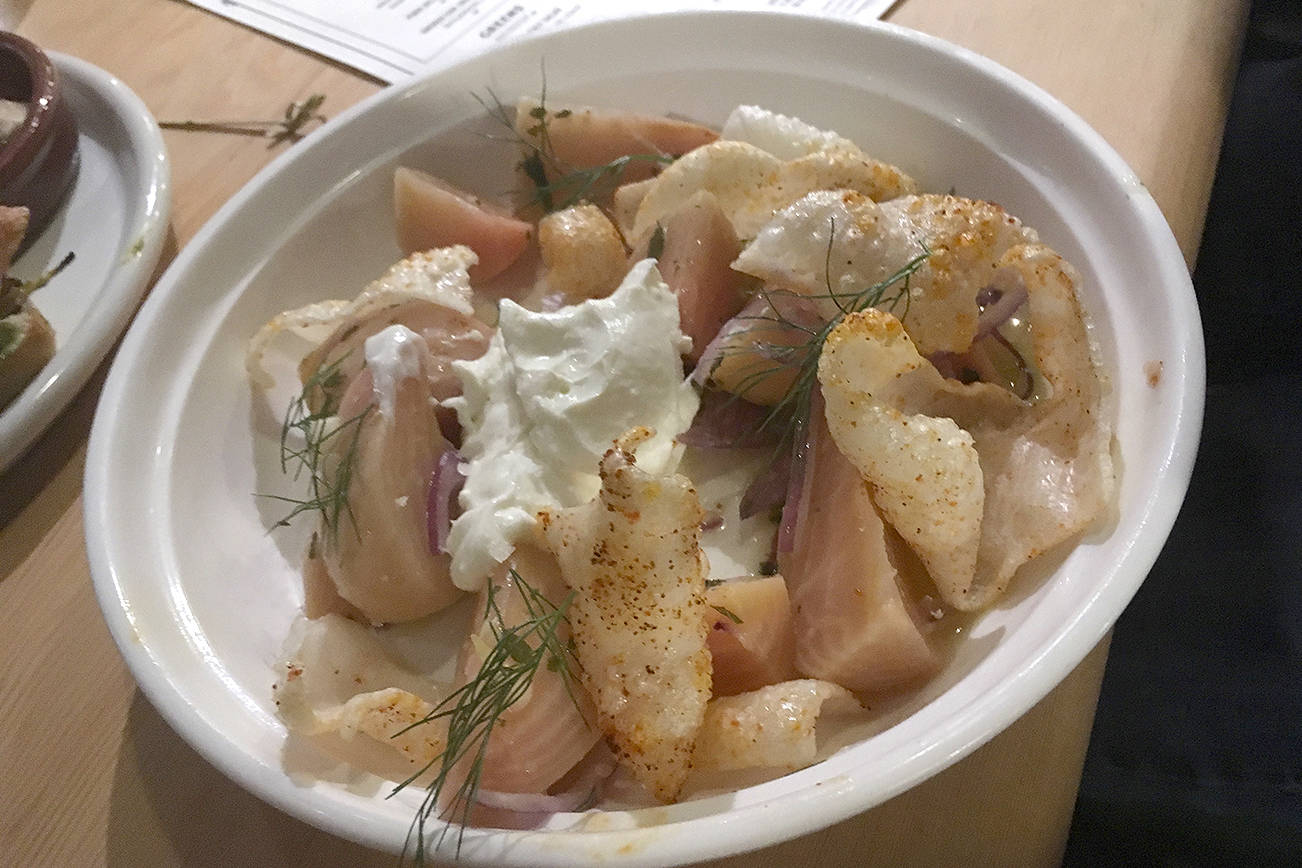

In New York, and now Boston, people have been going bananas for Dig Inn, a fast-food restaurant that sources nutritious ingredients from partners and farms with high-minded values, allowing diners who pay $10 to build out bowls that pile on sustainably sourced proteins like steak, chicken, and salmon, wholesome grains like quinoa, and rotating seasonal vegetables such as roasted squash and black kale, feta, and tomato salad. Indeed, I visited one of its many locations in Manhattan this summer, and was amazed by the lines out the door at lunch time.

Here in Seattle, the opening of the California-based Veggie Grill a few years ago signaled the arrival of the first strictly vegan fast-food restaurant, and it too garners lines at lunch time, particularly in the South Lake Union location where hungry Amazonians seek buffalo wings and “Chickin” sandwiches made from meat substitutes such as tempeh and soy, all organic and non-GMO.

But it has been in the past year that Seattle has witnessed a true sea change in better fast-food options, both in quality and variety, including Josh Henderson’s Great State Burger, where the meat comes from grass-fed cows, and Bok a Bok Fried Chicken, which sources only sustainably raised chickens for its Korean-inspired flavors. Besides tastier food, many of these spots also offer a more distinctive dining experience than chains like McDonald’s with trendier decor and fun additions that include local beers and housemade condiments.

Josh Henderson, one of Seattle’s most prolific and successful restauranteurs who, via his Huxley Wallace Collective, owns a number of tony restaurants such as Westward, Scout, and Quality Athletics, is behind Great State Burger in part because he believes that it is important for restaurant groups with big portfolios to diversify. But he’s also passionate about changing the way Americans eat, about “creating a burger we feel good feeding to our kids.” He says it only makes sense that chefs behind the farm-to-table restaurants, those who have spent their careers seeking better ingredients, would be part of this movement. “If you’re not paying attention to it now as a fast-food company, you’re going to get lapped.”

(Don’t Miss: Our full guide to the best fast-foodie spots, including Henderson’s Great State Burger.)

But Henderson is also quick to point out that the processes that fast-food chains like McDonald’s have perfected can’t be cut out completely. “I would argue that if you want to change the fast-food game, you have to use the efficiencies that they use but slip in a grass-fed burger.” He’s speaking about things like a clamshell grill that allows a burger to be cooked in a minute and a half, a common fast-food staple. While he concedes that such equipment takes away from the romanticism of someone suffering over a grill, it’s the only way to scale. “We spent all this time modernizing our food, starting with TV dinners in the ’50s,” he says, ”so if we can reverse that process—use the same techniques but bring in better ingredients—than we can really make a difference.”

While most of these upgraded fast-food restaurants exist only in urban centers where affluent people live and work—for example, Great State in South Lake Union and Laurelhurst—Henderson says he has plans to take the burger joint into the McDonald’s, or at least the In-N-Out Burger, lane, where the masses can have access to his almost entirely organic menu. “It’s the classic example of poor people getting the shaft, whether it’s credit cards or food,” he says. “We have a very strong desire to put our burgers in the mouths of people who don’t typically eat them. …That’s part of the plan, but we need to make a really good burger first. We have to work on a better bun. Even cheese has to be a quarter-inch wider. Is there one tomato or two, is the pickle on there or not? These are hard questions in the fast-food business.” And there aren’t always easy solutions. Though Henderson has purchasing leverage thanks to his large portfolio of restaurants, he admits that it’s a challenge finding someone who can make, say, an organic hamburger bun, but who can also handle volume.

Meanwhile, over in White Center, chef Brian O’Conner recently opened the wildly popular Korean fried-chicken joint Bok a Bok. It’s his first restaurant, and he lucked into a location where rent is a steal compared to, say, Capitol Hill or South Lake Union. But despite its slightly out-of-the-way neighborhood, people are coming from all over to savor his spicy fried chicken, kimchi mac ’n’ cheese, and other unique delights. Like Henderson, he’s committed to ethical sourcing, using sustainably raised chickens, making biscuits in-house, and even gathering herbs from his very own garden. The business also composts everything. Asked about the challenges of keeping prices low while serving a superior product, he says it’s all about overhead, or lack thereof. “There’s really not a front of the house, and everyone does everything. Customer service is still important, though, and we like to hire personalities.”

He’s right: The bare-bones space with a handful of tables and the minimalist logo of a chicken writ large on the wall doesn’t take much to maintain. You order food at a window from a cashier and get a number, and it’s delivered to you on a plastic tray that you then bus yourself. It’s an important point to underscore: Even Henderson’s places, while bigger and in neighborhoods with pricier rents, have far less staff and minimal decor. It’s these cost-cutting measures that allow them to put the extra dollars into the ingredients.

“As a chef, there’s a responsibility,” O’Conner says. “We have to look at where we’re getting our product from. … People are rejecting [places like McDonald’s]. In the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, we saw lots of processed foods. I’m glad to see that’s changing.”

While O’Conner chose White Center because it was financially advantageous for him—“I don’t have giant backers behind me. I put my whole restaurant together for $130K”—he does see the silver lining in being able to also serve his food to the community that lives there, a less-privileged demographic than in many other places in the city. On the night I reviewed the restaurant, people from the neighborhood poured in. It was refreshing. And that’s what’s heartening about this whole trajectory: It isn’t going to happen overnight; but little by little, as more committed, compassionate chefs continue to cook food that’s wholesome, delicious, and affordable, there just may be a chance to turn the tide on how all Americans eat. McDonald’s may be changing its game, and that’s a good thing, but at the end of the day it’s the chefs in places like Seattle that truly instigated it.

food@seattleweekly.com