The Bernard family’s summer wear in 1901 included a three-piece suit, a pair of wool coats, flannel and denim dresses, and high boots and wide-brimmed hats all around. With wife Gladys leaning back in a fold-out recliner, her husband William in a dark wood rocker, and their daughter seated nearby, the Bernards look content to the point of boredom at their beachside tent in Alki.

This family picture is a telling look at summer life on Puget Sound, where then, as now, the weather was as likely to require wool coats and warm hats as shorts and tank tops. It’s also emblematic of West Seattle at the turn of the century—a place where the wealthy of Seattle proper would spend their summers, soaking up what were often the warmest temperatures and the most sunshine that could be squeezed out of the region. It’s because the photo showcases the resort-style atmosphere the neighborhood was known for that the editors of Arcadia Publishing’s new Images of America: West Seattle say they picked it as the book’s cover image.

Today the original photograph sits in a cardboard box full of others like it at the Port Angeles home of Peggy Taylor, the widowed wife of Gladys Bernard’s grandson. Taylor says its use on the cover of an historical book is fitting. “I’m not surprised,” says the 68-year-old. “The Bernards were high society.”

The Images of America series uses photos, captions, and essays to chronicle regional locations throughout the country and the businesses, professionals, and residents who have occupied them. The West Seattle book, however, is special not only because it illustrates the city’s birthplace—the spot Arthur and David Denny and their families and fellow explorers first came ashore in the fall of 1851—but also because West Seattle is by far the most self-sufficient and independent of Jet City’s many neighborhoods, making its history that much more poignant.

The team who put the book together includes folks like Don Kelstrom and Rob Carney—not career historians, but locals with an eye for detail and a suitably open schedule for years spent sorting through old photographs and records.

Presently, these history buffs are gathered around Kelstrom’s dining-room table on a rainy night in January, explaining how they worked “like detectives” to put together an entire book based on historic photos—many with few clues as to who is in them or where and when they were taken. “We’d get the photos in from donations—sometimes there would be a note or something with some clues about it, sometimes nothing,” says Kelstrom, 67, a soft-spoken retired financial analyst whose cedar-shingled house near Fauntleroy is a few miles from where the Dennys first landed. “From there we tried to put names on people and see if anyone could recognize the place the pictures were taken.”

The gathering and sleuthing process lasted nearly three years. By the end, the group had more than 500 photos for a book that could hold less than 200. “It was tricky to arrange all the photos we wanted,” says Carney, 50, an electrical-material salesman and a bearded bear of a man with a perpetual smile. “We all had our own babies that we wanted in there, but we couldn’t get them all.”

The book’s photos are sorted into chapters by neighborhood and theme: “Admiral District,” “Community,” “Fauntleroy,” “Getting to West Seattle,” and “Alki”—whose pronunciation, Carney explains, changed from Alk-ee to Alk-eye during Prohibition, for obvious reasons.

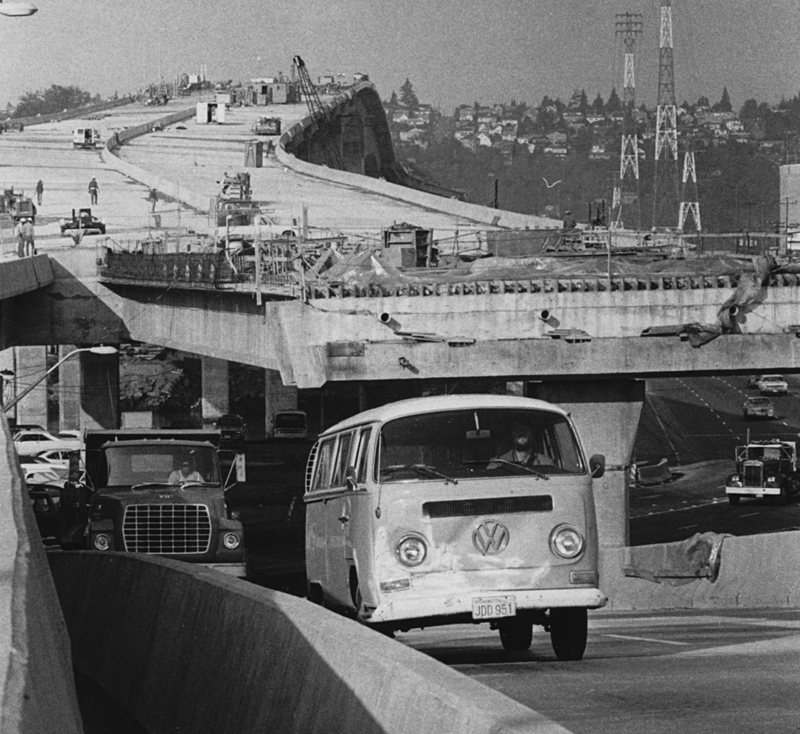

West Seattle’s evolving history is also captured in the book, from the “Mosquito Fleet” of small steamships and stern-wheelers that carted people around in the mid- and late 1800s and early 1900s to the 1937 streetcar accident that killed three and injured 59; from the Spokane Street Bridge that was struck by a freighter and rendered half-useless in 1978 to the West Seattle Bridge that in 1983 at long last replaced it, rung in with a raging “bridge party” at Lincoln Park.

The neighborhood’s most famous businesses and landmarks are documented too. There’s Busey’s Drive-In Restaurant in White Center with its oversized, roof-mounted root-beer barrels. The rugged-looking Alki Point Lighthouse, photographed just after its completion in 1913. And of course Luna Park, the short-lived but much-loved amusement park that graced Duwamish Head on the neighborhood’s north tip from 1907 to 1913 and is still used by locals to describe the area.

All told, the 160 years of history represented in the book is an eyeblink compared to that of much older locations on the East Coast and overseas. But in the context of the Puget Sound region and the West Coast as a whole, says Carney, understanding West Seattle is as important as understanding anything slightly east of it.

“This is where it all started,” he says. “It’s a place that gets in your blood if you let it.”