In his 1996 book of essays, The Size of Thoughts, Nicholson Baker includes a remarkable work of cerebral passion on the nation’s rapidly disappearing library card catalogs. “[H]undreds of card catalogs,” he writes,

tens of millions of individual cards—cards typed on manual typewriters and early electric models; cards printed by the Library of Congress, Baker & Taylor, and OCLC; cards whose subject heads were erased with special power erasers, resembling soldering irons, and overtyped in red; cards that have been multiply revised, copied on early models of the Xerox copier, corrected in pencil, color-coded, sleeved in plastic; cards that were handwritten at the turn of the century; cards that were interfiled by generations of staffers, their edges softened by innumerable inquiring patrons—have been partially or completely destroyed. . . .

Baker calls the cavalier replacement of dependable card catalogs with demonstrably unreliable online computer catalog systems “this national paroxysm of shortsightedness and anti-intellectualism” and finds it astounding that “nobody is making an audible fuss about what [library administrators] are up to. Nobody is grieving.”

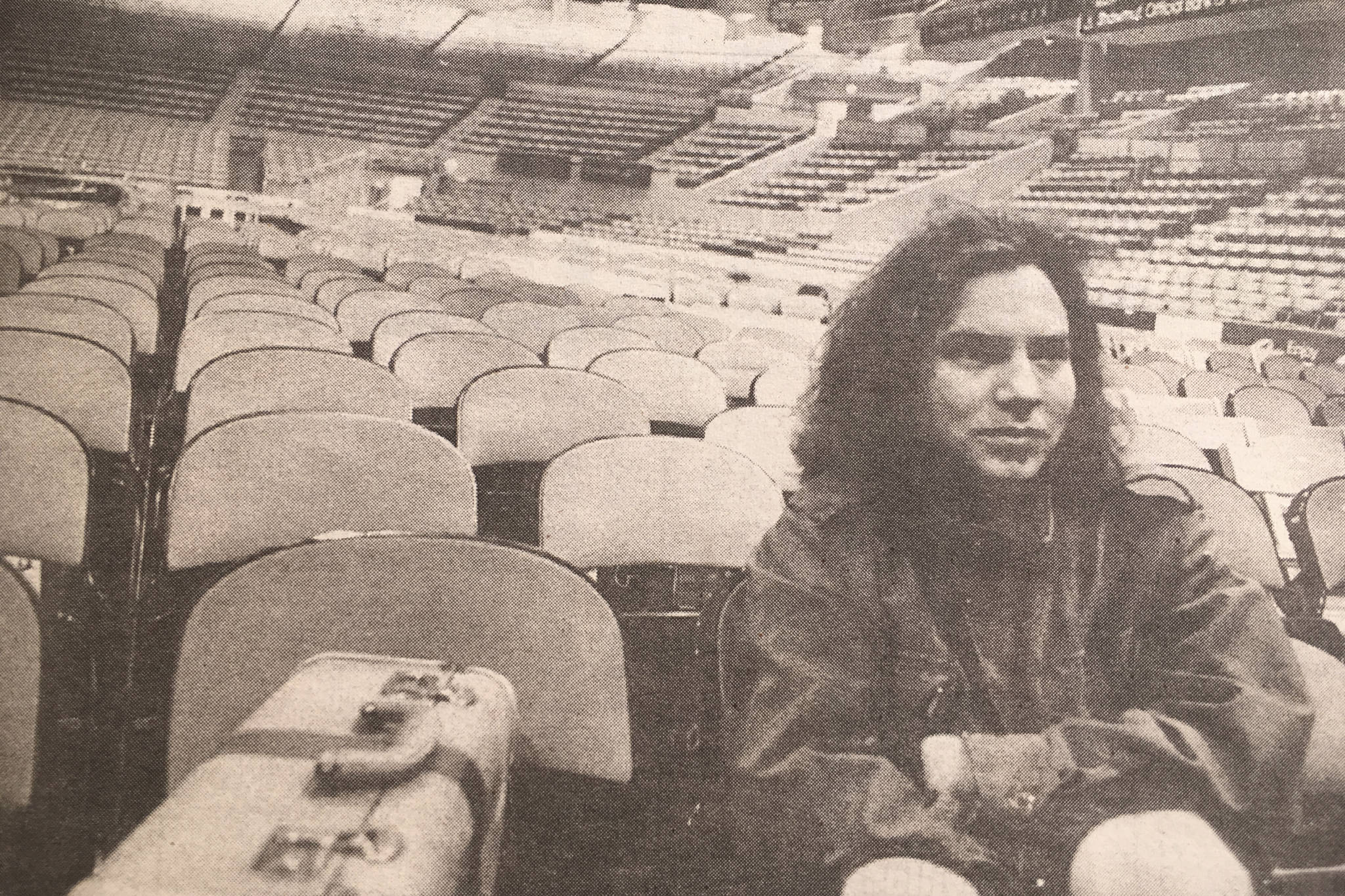

Or so he thought. In 1993, in the course of working on “Discards,” Baker—who is an indefatigable researcher—came across, in a series of discoveries of “card hoarders,” what he calls “the biggest and most heroic hoarder of them all”: painter and conceptual artist Tom Johnston, a professor in the art department at Western Washington University, in Bellingham. Johnston had contacted Harvard University and asked that it forward its discarded Widener Library cards to him. The university obliged—albeit only after Johnston agreed to pay the postage—and he now owns “a little over a million cards,” he told me recently.

Aside from a couple of small projects involving a few cards, the collection, Johnston says, “has sort of been lying fallow for a couple of years. I’m just sort of getting back to them now.”

Johnston did not call for the cards because he had a particular plan in mind for them. He was driven—in a way that any devoted library patron can understand—by an irrational urge to stave off their oblivion. “I felt like I just sort of needed to save them from being destroyed,” he says. Five years later, he has become the quasi-voluntary custodian of a resource he wants to put to a use commensurate with the value—both symbolic and otherwise—of card catalogs. “I don’t know what I’m going to really do with them,” he says. “The possibilities could be endless. I was thinking of suspending the cards on really thin fishing line, in a large space, making ‘a cloud of knowledge,’ or a ‘cloud of reference’ suspended overhead. Or I’d sort of like to do something with the entirety of them, sort of a sculptural mass.”

It is interesting to note that Johnston feels no particular sense of ownership of his collection. His motivation in stockpiling catalog cards is as unselfish in its way as the devotion of generations of librarians in maintaining the integrity of the information they contained. Just as when the catalogs were effectively owned by their community of users, the cards Johnston is preserving now belong to the world’s community of artists and others interested in “grieving,” as Nicholson would have it, or in preserving the memory of their function and symbolism. “I’m sort of holding them,” he says modestly. “I’ve invited other artists to do things with them.”

Fred Moody’s next book, The Visionary Position, will be published by Random House in February.