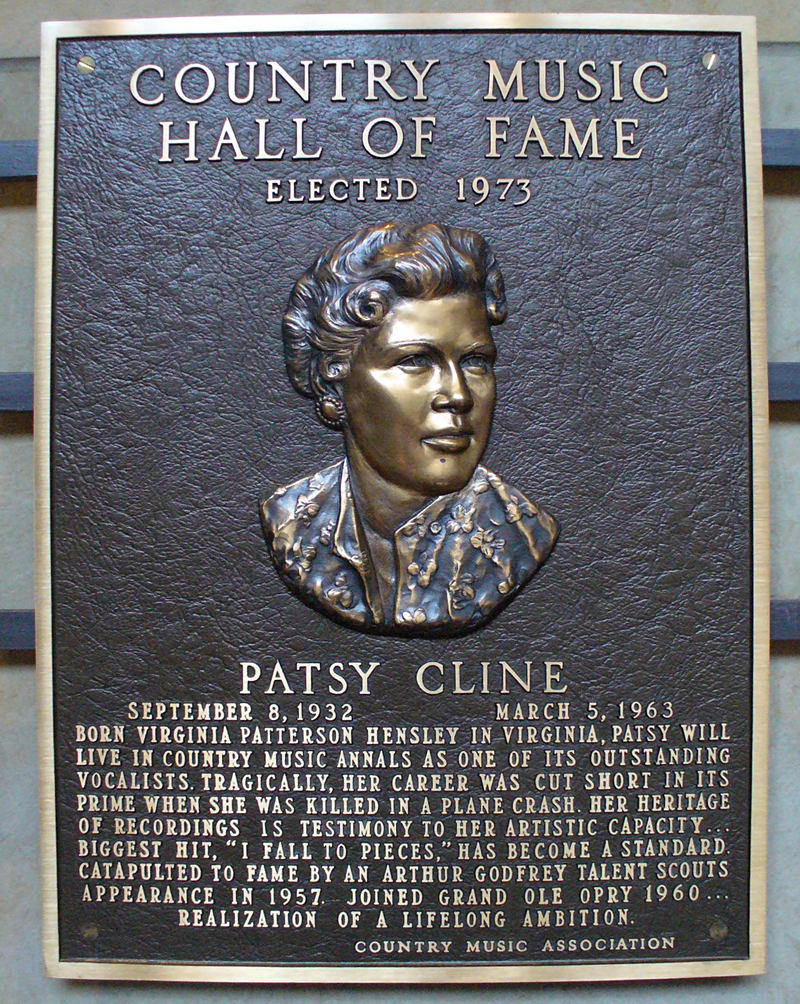

“Technique,” said composer/accordionist Pauline Oliveros, “is the ability to make your art come out the way you want it to.” Too often we think of these two things—the technique and the way-you-want-it-to part, i.e., the expression—not merely as two different things, but as antithetical: empty virtuosity as the enemy of emotional truth. But for any great artist, creative or performing, artistic intent and the ability to realize it must interdepend. For example, listen to Michael Bolton sing, on his misbegotten 1997 Christmas album, Schubert’s “Ave Maria”—he can’t get through the six notes of the first phrase without gasping for breath. That pause was not an expressive nuance; that was because his lungs gave out. By the same token, when I play the piano, the tempo, color, and phrasing of a piece is decided, more than by anything else, by the non-dexterity of my fingers. On the other hand, there’s Patsy Cline; it may seem odd to think of her as a “technician,” but it’s clear she can do anything at all she wants to with a song. Hear the end of her recording of “Faded Love,” the catch in the throat, the trembling gasp: It’s all deployed for maximum emotional effect yet sounds as unstudied as birdsong. You hear her sing “Crazy,” and you don’t think of the tune’s extreme difficulty. Try singing it yourself, then marvel again at her effortless mastery of its Schoenbergian angularity—and then beyond that at the way that mastery allows her to pull you into the lyrics’ poignantly subdued bitterness. This week, on what would have been Cline’s 79th birthday, Star Anna and the Laughing Dogs, Kim Virant, and many other local musicians offer a revue of her hits, called Sweet Dreams: The Music of Patsy Cline. Had she not died in a 1963 plane crash, she’d surely still be going strong, her status alongside Sinatra, Presley, and Cash untouchable. Many rank her up there already.

Ear Supply: Patsy Cline Can Do No Wrong

Her songs do anything she wants them to.