For its first 200 pages or so, Bill Buford’s Heat (Knopf, $25.95) appears to be—no, is—a deft conflation of two currently popular genres of nonfiction: the kitchen memoir (dirty doings behind the swinging steel doors of a three-star restaurant) and the unauthorized warts-and-all celebrity profile. Buford, hitherto best known as the American editor of the British mass-market little-magazine Granta, was lured back to the U.S. in the 1990s to be fiction editor of The New Yorker. But the same itch to escape the muffled world of the literateur that led to his immersion in the English soccer-hooligan scene (Among the Thugs, 1992) led him, a complacent amateur gourmet cook in his 40s, to nag himself into a job as an unpaid “slave” in the kitchen of the hottest chef (Mario Batali) and hottest restaurant in America (Babbo).

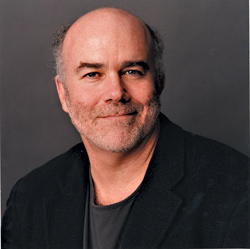

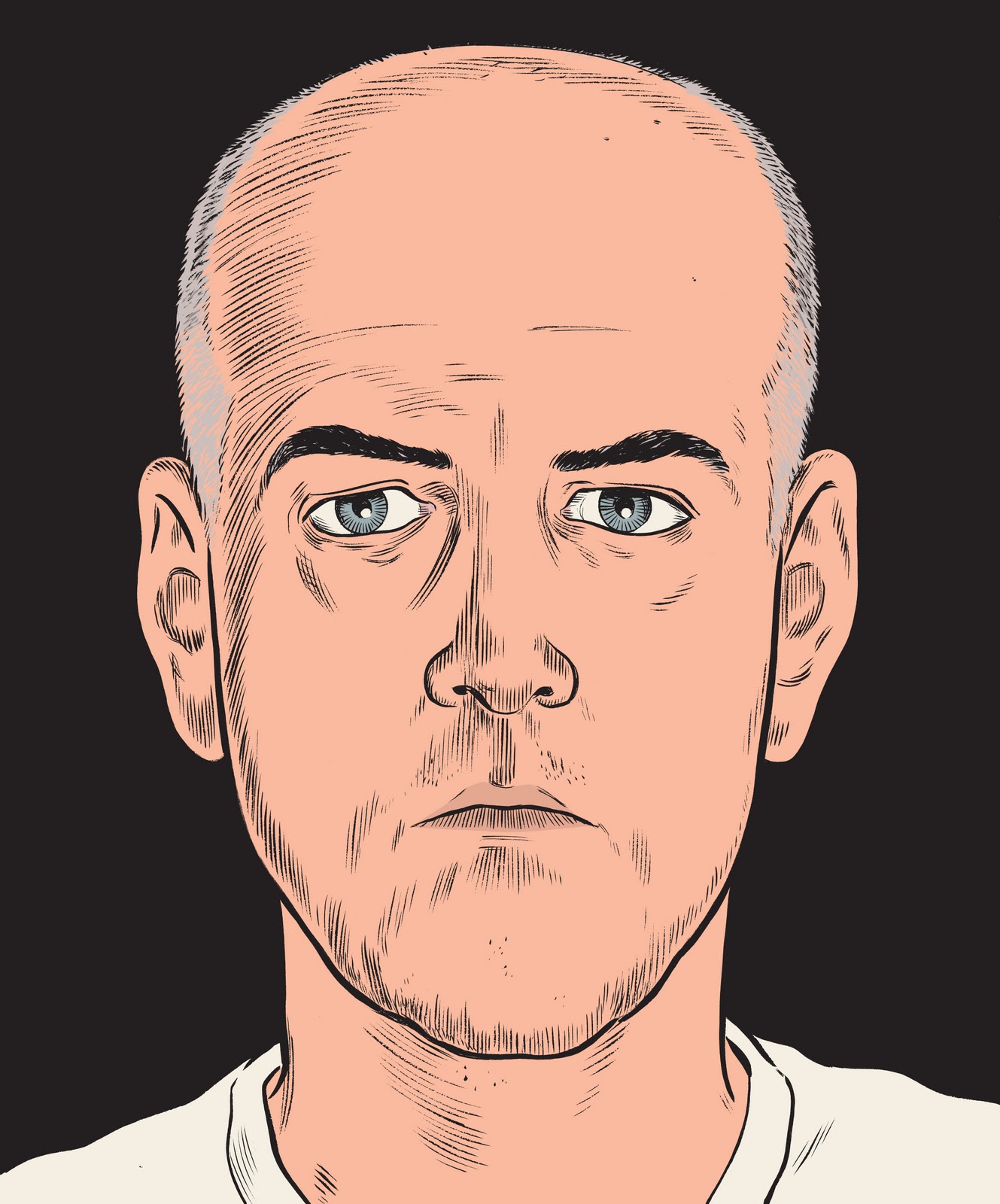

Buford published an account of his adventurous year working his way up from appetizers to pasta in The New Yorker‘s memorable first “food issue,” so a lot of what the author saw, smelled, and felt in the Babbo kitchen will already be familiar to people who can’t resist this kind of food writing. But it would be a shame if nonfoodies passed on the book, because its interest extends far beyond the culinary. In an almost creepy way, Heat reads like a sequel to Among the Thugs: No eye gouging or tooth smashing this time around, but the same musky, almost unbearably heavy reek of testosterone pervades the book. In person, Buford is a sophisticated, almost scholarly individual, but his literary persona is a latter-day Candide, wide-eyed, constantly astonished but never repelled by the fetid crevices and sweaty exudations of the men surrounding him. You get the feeling that he was the kind of kid you could get to take any dare in junior high for the privilege of being allowed into the gang, an object of both admiration and derision.

A paradox hovers just below the surface through the first two-thirds of Heat. Only a few pages in, we read an acknowledgment that women are by far better cooks than men. No one ever challenges that dictum. Yet Babbo’s world, despite the presence of women in its kitchen, is wholly male-dominated, and the kind of food Buford learns to make is wholly male in conception, execution, and presentation. It’s as if someone granted that women were better than men at childbearing and then devoted 300 pages to men simulating the process. Every time Buford mentions his wife, it’s a jolt. Even in the latter parts of the book, where she turns up from time to time in person, she plays about as significant a role as a confused noise offstage.

Buford never attempts to account for machismo in the kitchen, which is more than a little frustrating—it’s like describing the devastation of a china shop without taking note of the bull producing it. But to do so would be to step outside the ingenuous persona he’s chosen as narrator. As the horizons of Buford’s story widen, as he travels to Europe to visit some of the stations on his master Mario’s apprenticeship, the book seems to lose focus. Men, more or less madmen, continue to be the central figures, but European kitchen macho lacks the grotty locker-room reek of the American variety.

But the loss of focus proves illusory. In fact, shortly before p. 300, we learn that we’ve been reading this book all wrong. In a matter of a few pages, Buford pulls off a literary master conjuror’s trick, takes us firmly authorially by the elbow for the first time, and leads us to, of all things, a cliff-hanger ending. I grant that this ending may impel some readers to hurl the book across the room, but I confess to being charmed. Literary snow jobs this graceful are few and far between. Heat delivers on its initial promise—we get gossip, we get passion and hilarity, fear and loathing—and then hands us complimentary dessert. With any luck, we won’t have to wait 15 more years for Buford to dazzle us again.