Halfway through a rehearsal of Dragon Lady, Sara Porkalob sings “I wish I could tell you that you are no child of pain, but you have my blood in your veins, and trouble’s a family trait.” Light floods in through the lofty windows in the UW rehearsal room as she plays her grandmother, looking down at imaginary newborn-baby Sara in her arms. Seconds later, Porkalob swiftly and seamlessly encompasses her own post-childbirth mother as well, exhausted and melting into a hospital bed. Three generations, 30 characters, and one epic, hilarious story of generational healing, resilience, and triumph are at the center of Dragon Lady.

I’m meeting with Porkalob amid rehearsals. Reflecting upon her grandmother’s life, Porkalob says, “She thinks that she’s accomplished nothing, but what she has done with her life is these incredible, hard, difficult, joyous things, and we as her family are going to take that as part of our integral identity.” Porkalob’s identity and the work she engages in on all fronts are interwoven. As an artist/activist, Porkalob is dedicated to the fight against white supremacy, patriarchy, and beyond, and Dragon Lady is an extension of this intersectional work.

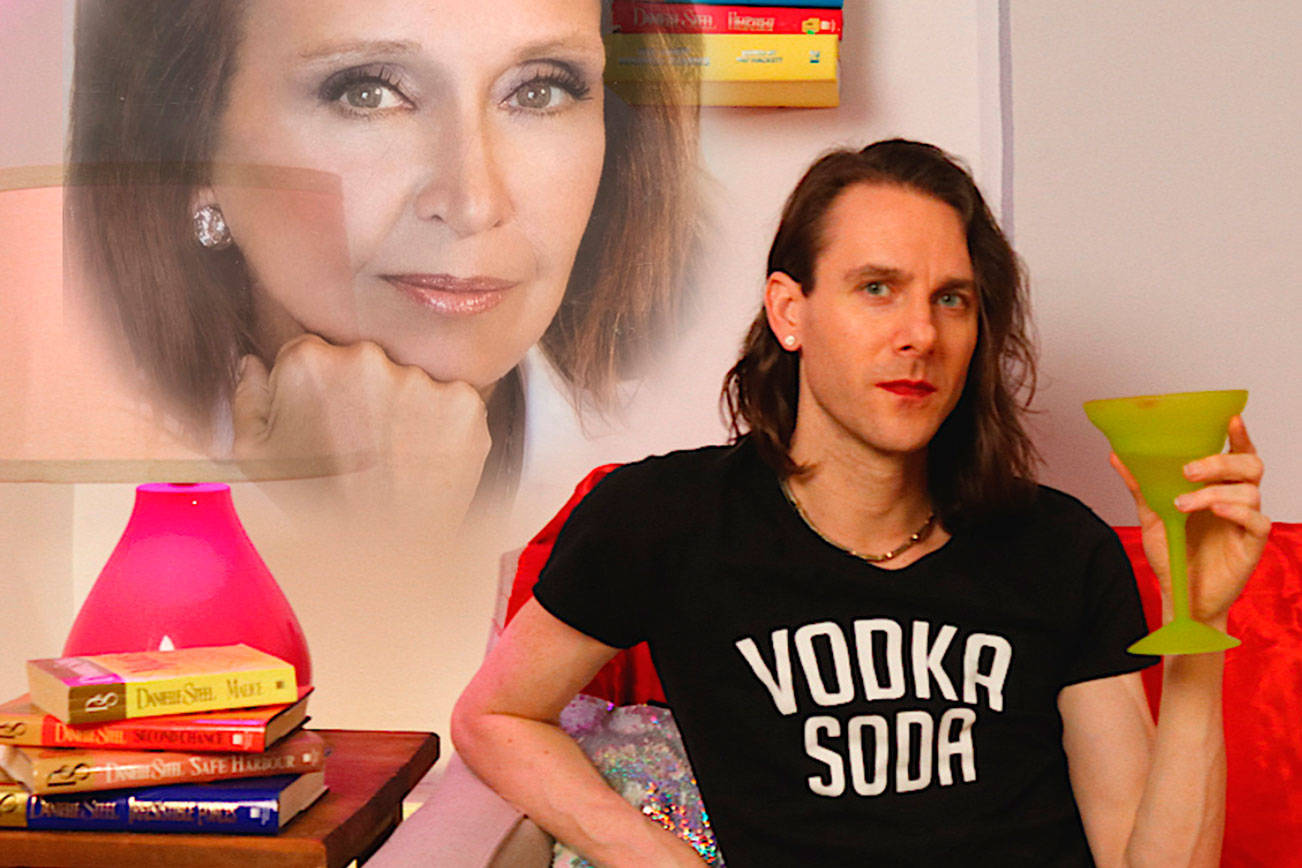

In the show, karaoke-loving Grandma Porkalob shares stories of her secret life in the Philippines, how and why she emigrated to America, and her experiences on American soil. The play is framed by Grandma’s decision to share these stories with Sara on her 60th birthday, her versions clashing with the tales that Porkalob’s mother, aunts, and uncles share. Veering from laugh-out-loud funny to intensely gut-wrenching, each scene delves into the nuances of Porkalob’s family history. Porkalob shifts quickly among characters in each scene, denoting changes physically and vocally. In this fashion, Dragon Lady is almost entirely a solo show, save for an exciting surprise appearance at the end.

Love, and her family, are huge motivating factors for Porkalob’s work. “My early childhood years were really formative,” she says. She was raised by her mothers in a QTPOC communal house in Anchorage, Alaska. “As a child that was just normal for me, and it really wasn’t until I hit college [when I realized] that had a huge impact on my life and how I see things.” In addition, Porkalob’s mothers “were really consistent and vocal. With their actions everyday they taught me that as a woman and as a person of color, I would go out into the world and I would be confronted everywhere I turned with this idea that my gender, my color, wasn’t enough, and that I had to change who I was in order to be acceptable to society.” Warning Sara of the internalization of these messages, her mothers also encouraged her: “Once you are able to either reclaim those identities or claim different aspects of your identity, then that’s really where your power and your knowledge will come from.”

After high school, Porkalob attended Cornish College of the Arts. The first two years there presented theater as a universal, human experience that transcended the individual. This framing was “missing the core of truth that is my experience, that is so many people’s experience.” It was not until her junior year that she began to see her own experiences reflected in the material she was studying, through a course on post-colonial theory and semiotics. The course presented ideas “I had known about outside of the theoretical terminology, being raised by queer parents,” she says, “but what I didn’t have yet was the language to assert my position in all of that theory as an individual body.” Finding this language was a turning point for Porkalob—the moment she began to use that language to resist the erasure of the experiences of people of color, queer and trans folks, and disabled folks in the theater. This resistance sparked her future work in the rehearsal room, board room, onstage, and beyond.

“Resistance is key,” Porkalob says, and one way she engages with this is to fuel work by POC theater-makers who are not confined to stories of trauma in the context of whiteness. “While trauma and violence is a part of our history … we have a lot to celebrate. We have joy. There’s resilience. There’s desire. There’s love. There’s hate. There’s redemption. All of those things belong to us to, not only white people,” she says. In recent work with the Intiman Emerging Artists Program, she’s prioritized the voices of emerging artists of color and the development of their own solo shows.

Porkalob is in an in-between place with her own show. “I’m really proud of the work that I’ve done, [but] I think one of the things that I have been struggling with is the prioritization of that work and feeling like in the current, relevant scheme of things this story isn’t necessarily the one that needs to be told right now,” she says of Dragon Lady. “I’ve been holding [Dragon Lady] in one hand, and also been holding all of the work that is being done in Seattle that focuses on black narratives [in the other]. As a woman of color, what I experience within the construct of white supremacy is not the same as a black woman … and I think it is really important to amplify … the work being done by black women in this town,” she says. Keeping herself accountable to the work she is doing is central to her process.

“Manifester” is a word that one of Porkalob’s close friends uses to describe her. The term is accurate in all areas of her life. At this moment, she is dreaming up a few things; for one, getting to the highest position of power she can so that she can make enough money to take care of her family. That, and “so I can use all of that power, influence, and money to focus on the fostering of young people of color. [That] is the dream.” There is no doubt she will manifest just that. Dragon Lady, The Floyd and Delores Jones Playhouse, 4045 University Way NE. $20–$50. All ages. Ends Sun., Oct. 1.

stage@seattleweekly.com