“What does it feel like to live in America right now?” Eight local playwrights—Holly Arsenault, Kelleen C. Blanchard, Tré Calhoun, Vincent Delaney, Brendan Healy, Maggie Lee, Sara Porkalob, and Seayoung Yim—joined forces five months ago to begin to answer this question. With responses ranging in form from monologues to group dance scenes, a play named American Archipelago came into being. American Archipelago has its moments—flashes of rich dialogue and meaningful character development—yet the production as a whole lacks cohesion. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise; weaving together eight narratives representing various American experiences is a tall order, and the result lacks a solid narrative structure. That said, American Archipelago succeeds in small, intimate scenes between a few particularly well-crafted characters.

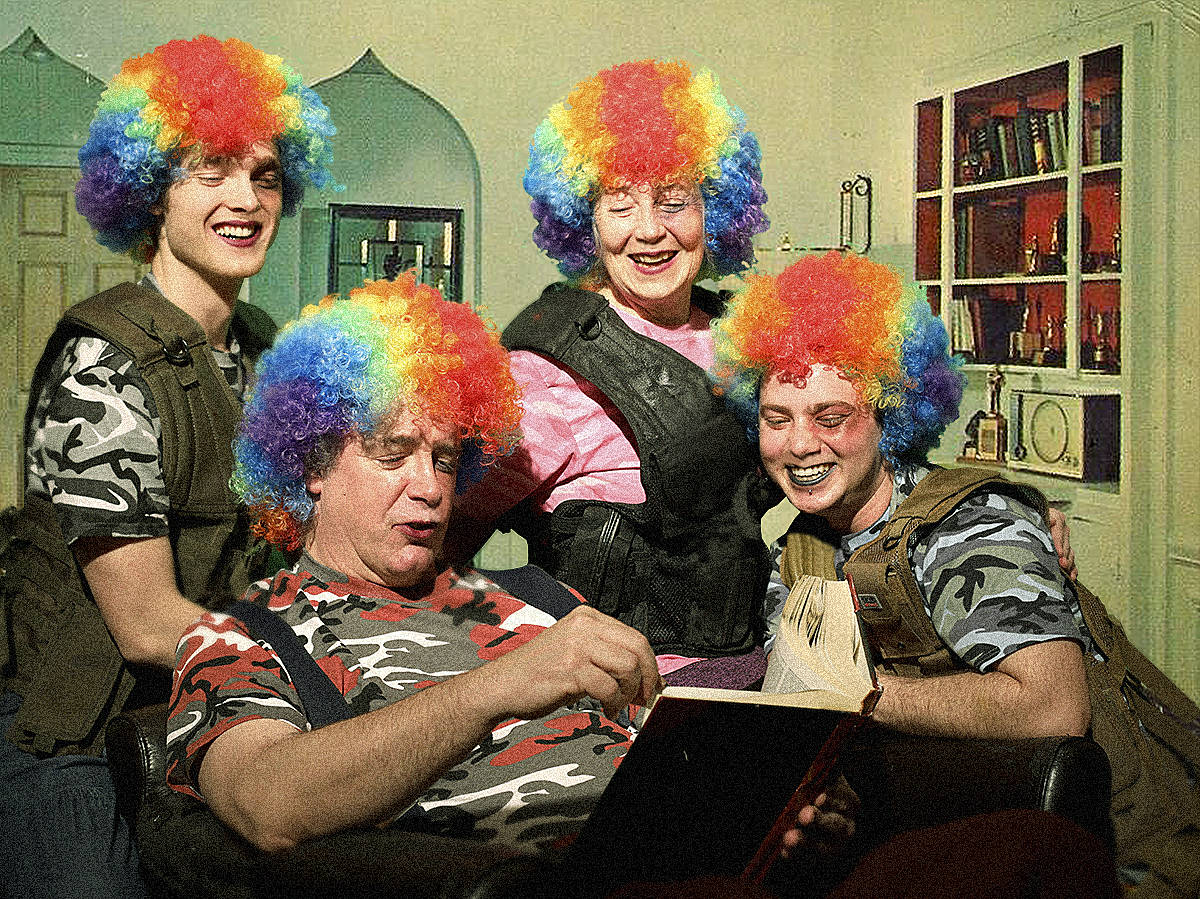

American Archipelago follows the story of eight different people, with identities that vary drastically across class, gender, and race, living in the United States. A block party and cookout brings the group together from all over the U.S. Folks gather as real-estate agent Bev, played exceptionally by Shermona Mitchell, shows the homes of the seven other characters to the public. Their stories pour forward as they interact, fall in love, argue, and share.

In one vignette, Julia, played by an animated and clever Corrine Magin, explores a kinky relationship with Luis (Carter Rodriquez). Throughout the play, they both confess to engaging with their anger and pain, informed by their histories as characters. Their erotic BDSM relationship consists of Julia throwing tomatoes at Luis. “I like being abused,” he says, looking for “a terrible love.” Near the beginning of the play, we discover that Luis is leaving Leonard (Bob Williams) during their conversation sitting in lawn chairs sharing a cheese plate. Leonard’s relationship to Luis is brief, and felt underdeveloped. Cursory moments similar to this reoccur throughout the play—a new story element is planted, then left untouched.

In one particularly poignant scene, Bev and Carl (Craig Peterson) discuss their marriage. Bev, who is black, calls out Carl on his whiteness, asking him to “leave me and my body to myself,” and explaining how his whiteness blinds him to her pain. Shortly after this, the narrative shifts and we come across a white woman who is obsessed with chickens and has adopted a daughter whom she treats like a chicken. The two stories are drastically different, and as an audience member the shift was disorienting. The importance and relevancy of Bev and Carl’s conversation as regards living in America was clear, but the narrative around chicken ownership and loneliness was foggy. If the intent in combining these miscellaneous stories was to compare the various pains of living in the United States, the rhythm and transitions between them lacked the clarity necessary to pull it off. I left searching for connections among the pockets of stories presented in American Archipelago, hungry for a deeper look into certain characters and perplexed by others.

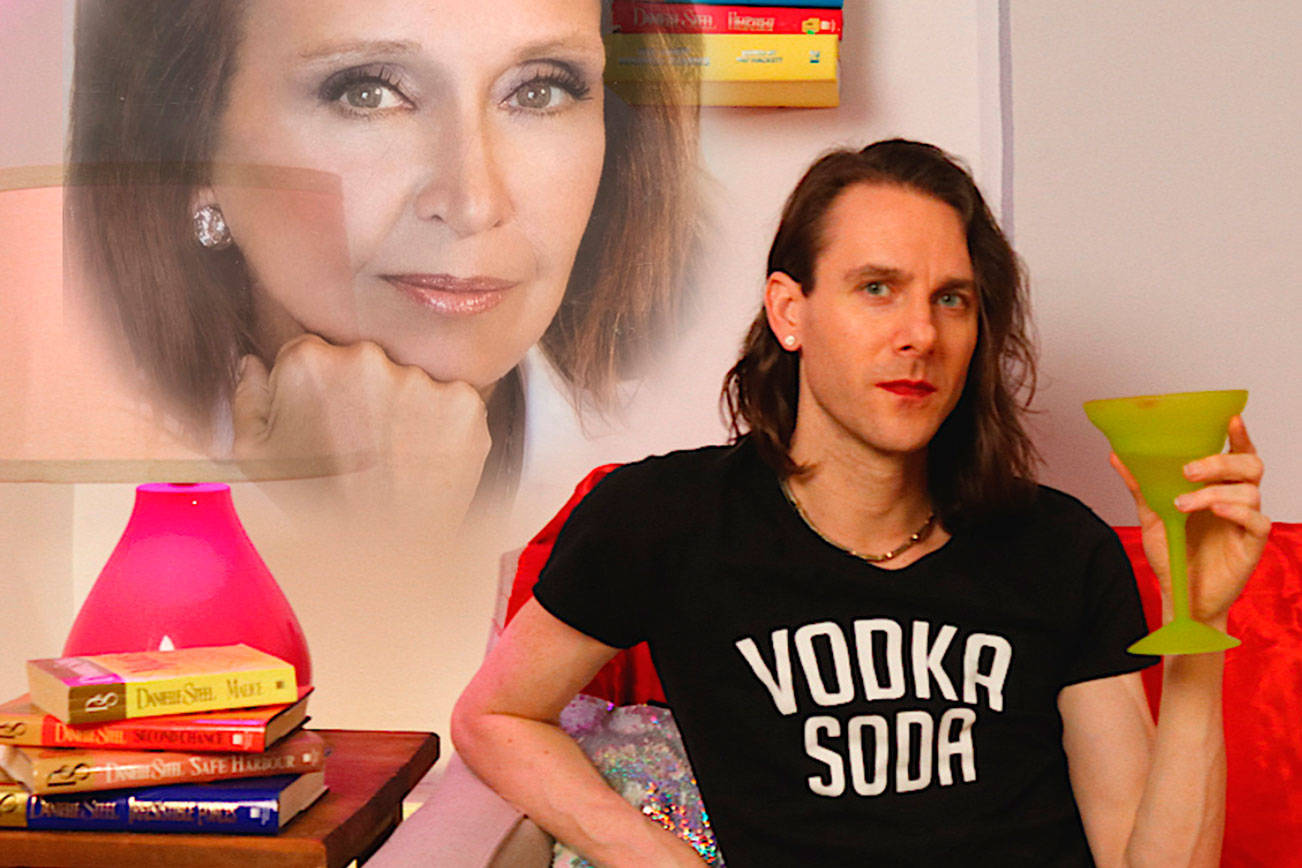

American Archipelago, Pony World Theatre, 12th Ave Arts, 1620 12th Ave., ponyworld.org, $10–$20. All ages. Ends Aug. 12.