As Seattle’s leaders put out the welcome mat for new housing density, individual neighborhoods continue to resist development. In the latest flash point, residents of the area south of Volunteer Park have joined together to fight the proposed demolition of a turn-of-the-century home.

The fighters are an unlikely collection of neighborhood residents energized by the potential loss of the elegant house at 611 13th Avenue East, which is slated to be replaced by a six-unit condominium project. “This is an issue not just for Capitol Hill, but for the whole city,” says JoAnne Seel, one of the leaders of the newly formed organization, Urban Balance. “You hear people saying, ‘Isn’t it a shame that they tore that house down?’ ‘Isn’t it a shame those trees are gone?'”

The 13th Avenue neighbors hope to use the city’s landmark process to preserve the 1904 house. While only about 200 structures in Seattle are designated landmarks (including the Maryland Apartments, located in the same block of 13th Avenue), this application is no long shot. The home was designed by noted architect Max Umbrecht: Its ornate facade reflects the Queen Anne and Victorian homes of the late-1800s. The house also had a noted former owner: Robert Hitchman, the longtime president of the Washington State Historical Society who wrote the 1985 book Place Names of Washington, lived there for 40 years. His newsletter on historical books was dubbed “Sighted from the Crow’s Nest,” after Hitchman’s nickname for the top-floor room in the house with its sweeping views of city and mountains.

Although the house is beautiful, well-kept, and quite valuable (builder Jason Kintzer paid $675,000 just for the opportunity to tear it down), other factors conspire in its possible demise. The Hitchman home was built on a double lot. And, unlike the homes just one block north, this lot is zoned for apartment construction; under the property’s L-3 zoning, an eight-unit apartment building could be constructed there. Kintzer hopes to build six luxury townhouses in his two-building project.

But Kintzer wants to build his structures closer to the street and to the back lot line than normally permitted, and to cover a larger-than-allowed portion of the lot. If these departures from the zoning are denied, Kintzer could propose a more standard apartment structure or sell the property.

Neighbors note that even a modified project would probably cause the removal of three massive elms on the property’s planting strip and a huge beech tree in the side yard.

Some residents complain than Kintzer hasn’t been terribly cooperative, but acknowledge that the builder and the neighborhood have far different aims. It didn’t help that, at the one meeting the developer attended, the first question aimed at him was “How can you do this? How can you destroy a beautiful home like this?”

Unlike in a standard “houses vs. apartments” battle, this section of 13th already includes several multifamily buildings—and many of the development project’s opponents are apartment dwellers. “We’ve got this really nice balance,” says Seel, who says she still wonders why the neighborhood’s underlying zoning is so dense.

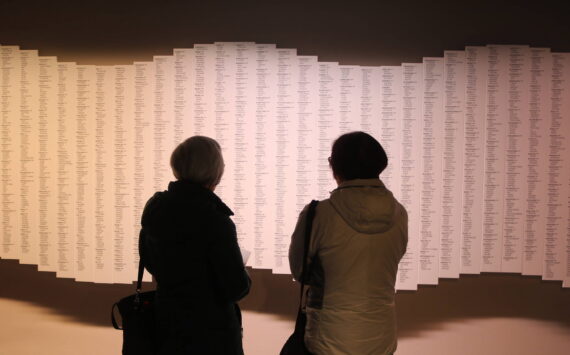

Although most of the Hitchman home’s protectors had no experience in neighborhood activism, says Seel, “these people are professionals and they know how to research.” (Group member Margaret Friedman learned of the home’s impending demolition by following a series of arrows chalked on the sidewalk to a posted city document.) Urban Balance members compiled the extensive landmark application for the home and documented the site with still photographs and video. Using fliers and other low-cost promotional techniques, Urban Balance has galvanized the neighborhood.

Some other possible city solutions would come too late for the Hitchman home. City regulators are exploring a proposal to preserve historic trees through agreements with property owners. Seel and other Urban Balance members are considering working on a city tree preservation ordinance. Friedman says the city’s efforts to draw new development to areas that want it won’t work if more units can be shoehorned into already-dense neighborhoods. “Unfortunately, developers are going for the fastest, surest buck,” she says. Allowing projects like this one, notes Friedman, “cuts down any incentive for developers to work in an area that needs development.”

This entire battle looks especially familiar to veterans of late-1980s land use wars in Seattle neighborhoods. Capitol Hill, one of 37 neighborhoods participating, recently had its neighborhood plan approved by the Seattle City Council. Weren’t these sorts of squabbles over individual developments going to be avoided through neighborhood planning?

“No, I don’t think anybody ever was that naive,” says Gary Lawrence, former city of Seattle planning director and a major architect of increasing density through the Seattle Comprehensive Plan, a.k.a. urban villages. The comprehensive plan “is a very blunt instrument, and I don’t think it ever was designed to resolve these lot-by-lot kinds of questions,” Lawrence says.

But neighborhood planners have to appreciate the numbers of people involved in the 13th Avenue fight. An initial meeting drew a standing-room-only crowd of 78 neighbors; in the three-and-a-half-year neighborhood planning process in one large Seattle neighborhood, only about 10 meetings drew that kind of a crowd.

Despite the successes of the neighborhood planning process, general planning discussions just can’t compete with the effect on the immediate neighborhood of a single controversial project. Lawrence notes, “It’s human nature to preserve your energy for the things you’re against.”