Hanford might start converting some of its worst radioactive wastes into benign glass in 2023. But that comes with an extra $4.5 billion added to the project’s costs — raising the price tag from $12.3 billion to $16.8 billion.

And it comes with the question of whether the incoming President Donald Trump and his Secretary of Energy nominee Rick Perry—who would oversee the department responsible for the cleanup—will buy into this new approach with the extra $4.5 billion price.

“I don’t think Rick Perry is aware of all (the federal) nuclear sites. … I don’t know if this administration will stick with it,” says Tom Carpenter, executive director of Hanford Challenge, an independent watchdog group.

The first time that the extra $4.5 million will show up in Congress’ Energy & Natural Resources Committee to begin the appropriations process will likely be in the spring, said an aide to Sen. Maria Cantwell, who is is on that committee. Sen. Patty Murray is on the Senate’s appropriations committee. Both have strongly backed funding Hanford’s cleanup.

On the GOP side, U.S. Rep Dan Newhouse, a Yakima Valley Republican, will be the point person for funding Hanford’s cleanup.

Glassifying radioactive wastes is the Hanford Nuclear Reservation’s biggest project, which has been plagued since the turn of the century with massive budget increases, technical problems and managerial glitches, plus several timetable delays. The original budget was $4 billion with the plant going online in 1999. Subsequent missed deadlines for startup were 2007, 2011 and 2019. Last year, Seattle Weekly published an in-depth look at the technical and managerial issues that have plagued the project for years.

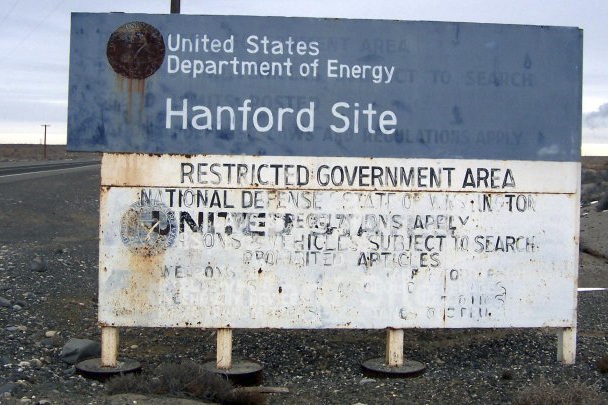

Hanford is arguably the most radioactively and chemically contaminated spot in the Western Hemisphere. Its greatest problem is 53 million gallons of highly radioactive flunks, sludges and chunks in 177 leak-prone underground tanks seven to 11 miles from the Columbia River. At least 1 million gallons have already leaked and are oozing to the river.

Hanford’s master plan since the early 1990s has been to convert those wastes into glass capable of lasting 10,000 years — enough time for the radioactivity to decay to much safer levels.

Last Friday, the U.S. Department of Energy announced it will build a fast-track facility to convert low-level radioactive fluids in the tanks into glass starting in 2023 as a way to get glassification going, a plan that would cause the bigger price tag. Meanwhile, DOE will continue to wrestle with major technological problems to build another facility to separate high-level radioactive materials from the sludges to be converted into glass in a proposed high-level radioactive waste treatment facility.

The state Department of Ecology has signed off on building the fast-track low-level-waste glassification plant by December 2023. “It is a tight schedule,” says Suzanne Dahl, the ecology department’s section manager for tank waste treatment, but the department believes DOE can get such a facility running by then.

The pretreatment plant, and the low-level and high-level glassification facilities, are now supposed to be all working by 2033. All 56 million gallons or nuclear wastes are to be converted into glass by 2047.

Nuclear waste cleanup at Hanford and nationwide received almost no attention in the presidential election, but that doesn’t mean the election won’t have a major impact on the cleanup efforts.

Trump’s nominee to head the Office of Management & Budget is U.S.Rep. Mick Mulvaney, R-S.C., a strong advocate of federal budget cutting. While Perry’s nomination has received extensive coverage on oil issues, the bulk of DOE’s work is on nuclear research, nuclear bombs, and the cleanup of nuclear sites — subjects in which he has provided no signals about.

Carpenter, with Hanford Challenge, also questions whether DOE has fixed its managerial issues enough to finish a low-level radioactive waste glassification plant by 2023. These problems include hostility to internal bad news. Contractors are tempted to cut corners when pressed to meet deadlines and financial incentives, he says.

Carpenter cites a 2015 General Accounting Office report that noted that DOE has unresolved design issues based on out-of-date approaches in its approach to fast-tracking a low-level waste glassification facility. The GAO is Congress’ investigative agency, and has routinely concluded in the past several years that DOE appears to underestimate costs on the entire glassification project. For years, the GAO believed the total project’s $12.3 billion estimate — prior to adding $4.5 billion — had been at least $1 billion too low.

However, DOE spokeswoman Yvonne Levardi said: “We are making progress on the technical operations.”

Carpenter, who says he does not oppose the fast-track option, is not convinced: “I worry about them taking shortcuts as they’ve always done when there’s pressure on them.”