IT IS HARD to see the current sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church clearly. Most people are viewing the scandal through a lens colored by their beliefs about organized religion, celibacy, an all-male priesthood, and the politics of the church.

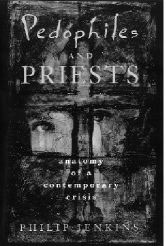

Wrestling with the issue this week, I came upon the work of Professor Philip Jenkins, who wrote about the mid-1980s “crisis” arising from the conviction of priests for sexual crimes against children in his book Pedophiles and Priests (Oxford University Press, 1996). He argues that many factors, including anti-Catholic prejudice, political interest groups within the church itself, mass media, the internal organization of the church, and the legal environment, resulted in a lack of understanding of the problem of sexual abuse itself and a distortion of how widespread the problem is within the priesthood.

Jenkins is not Catholic and insists he is not a “Catholic apologist.” He wrote last month in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “My research of cases over the past 20 years indicates no evidence whatsoever that Catholic or other celibate clergy are any more likely to be involved in misconduct or abuse than clergy of any other denomination—or indeed than nonclergy. However determined news media may be to see this affair as a crisis of celibacy, the charge is just unsupported.”

In his book, Jenkins points out that there are a couple of reasons we hear more about abuse within the Catholic Church than in other religions. First, there are a lot of Catholics in the country, some 60 million Americans, almost one-quarter of the population. Secondly, the Catholic Church is organized in a strict hierarchy. Each diocese is required by the Vatican to document all of the complaints against all of its priests and keep the records in a central location. Attorneys can subpoena those records and use them to buttress their clients’ claims. “The fact that the church kept such records has probably been the largest single element in inflating the number of Catholic clergy who have come to the attention of the courts,” Jenkins says. He goes on to point out that the second largest denomination in the U.S., Baptists—with 30 million members—are organized along strictly congregational lines. Each individual Baptist church organizes itself, so there is no centralized storehouse of accusations of misconduct to subpoena.

The abuse scandal is also inflamed by the very real conflicts within the church, Jenkins argues. Conservative Catholics have used the scandal as an opportunity to push for strictures against gay priests (I find the attempt to link homosexuality and sexual crimes against children highly offensive). Liberal and feminist Catholics have seen the scandal as an opportunity to push for the ordination of women. (There would seem to be a basis for this, because 90 percent of sexual abuse of children is committed by men, according to a survey of research by David Finkelhor, a professor at the University of New Hampshire.) These groups have also used the opportunity to attack celibacy (whatever problems there are with celibacy, I found no academic literature to support a relationship between it and sex crimes). Jenkins believes the media seized upon the resulting political sparks to fan the flames of the crisis.

Jenkins also argues that the best evidence on sexual crimes by priests shows the incidence of misconduct is less than 2 percent. He takes as his source a “bold and thorough self-study” by the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago in the wake of the last “crisis.” A commission appointed by Joseph Cardinal Bernardin examined the personnel files of all the priests—some 2,252 individuals—who served in the Chicago dioceses between 1951 and 1991. The commission also reopened every “internal complaint made against these men.” Jenkins explains, “The standard of evidence applied was not legal proof that would stand up in a court of law but just the consensus that a particular charge was probably justified. By this low standard, the survey found that about 40 priests, about 1.8 percent of the whole, were probably guilty of misconduct with minors at some point in their careers.” Jenkins points out, “Since other organizations dealing with children have not undertaken such comprehensive studies, we have no idea whether the Catholic figure is better or worse than the rate for schoolteachers, residential home counselors, social workers, or scout masters.”