The King County Sheriff’s Office has been stonewalling its oversight agency for months, according to Deborah Jacobs, director of the Office of Law Enforcement Oversight. Calling the act of giving feedback to the Sheriff’s office a “struggle,” Jacobs listed several specific complaints against KCSO’s conduct at a meeting of the King County Council’s Law and Justice committee on Tuesday.

“Sometimes they take [our feedback], sometimes they don’t,” she said. Next year, she said, she plans to continue “fighting” for the creation of a fully-realized police oversight agency.

Addressing Councilmembers Jeanne Kohl-Welles, Joe McDermott and committee chair Larry Gossett, Jacobs said that in one instance last year, the Sheriff’s Office erroneously believed that OLEO staff were viewing documents that the didn’t have authorization to access, but did not confront OLEO with this accusation. Jacobs, who said she only learned about it later through a third party, contrasted this against OLEO’s actual style: “We’re not into surprises,” she said.

“We constantly endure a lot of delays, whether we’re trying to get information or legal analysis,” said Jacobs. “It’s really a plodding effort at times.” She told the Council that OLEO and the Sheriff’s Office are both working on use-of-force reviews, and each hired a consultant firm for data analysis. According to Jacobs, the Sheriff’s Office refuses to share its information with OLEO. “I can’t get the data,” she said. “I’ve been asking since June. I go around and around.”

“I could do a public records act request to get it, but I don’t want to because of the precedent [that would set],” said Jacobs. “We should have a right to that data.”

“That is not tenable,” said Gossett. “We are all one government.”

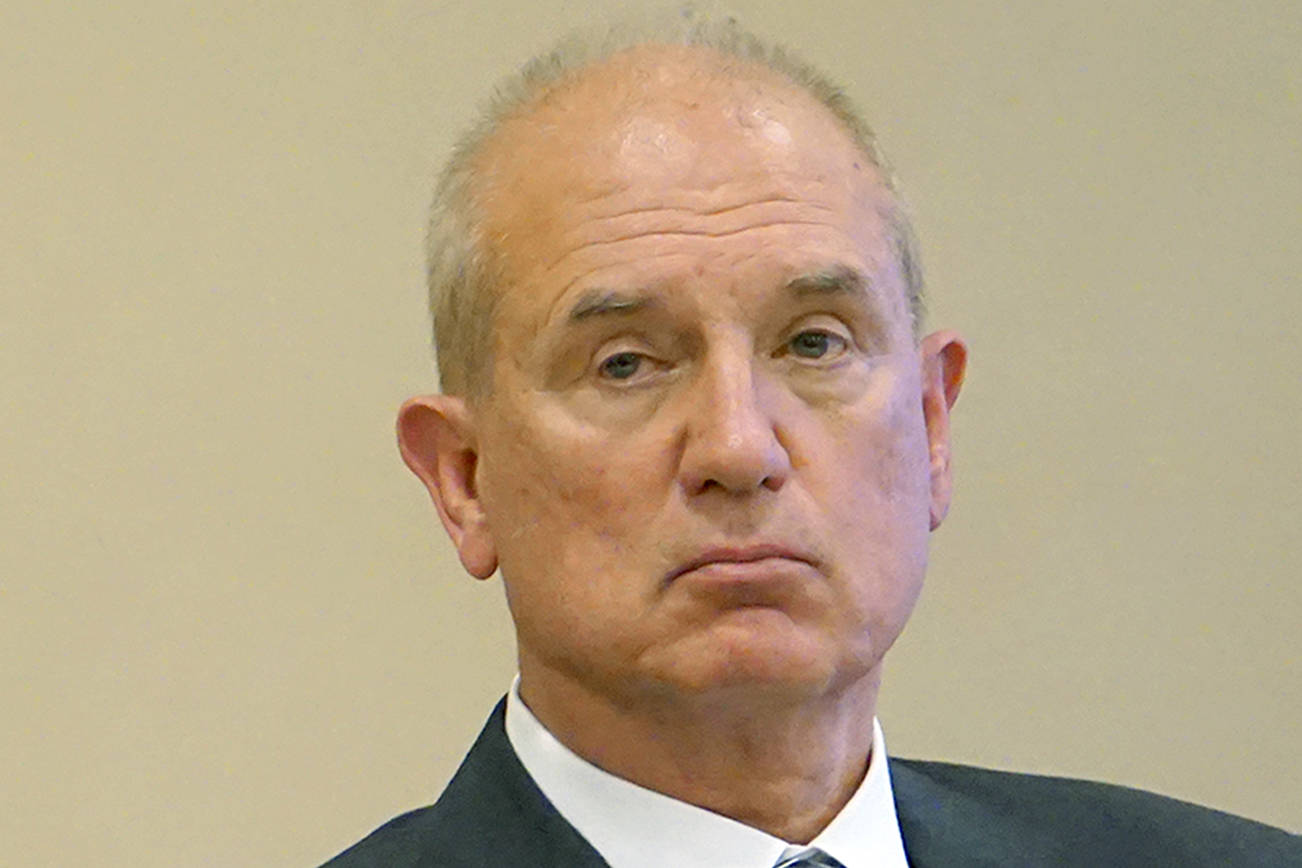

Sheriff John Urquhart responded via email to Seattle Weekly’s questions about Jacob’s statements. “Deborah is being a bit ‘dramatic’ in her testimony,” he said. “It’s too bad I wasn’t there to refute what she had to say. So I’ll do it here.”

Urquhart said he was barred by labor rules from sharing their use-of-force data: “The information she is requesting was denied because a release is prohibited by the Guild contract, and she knows that. I asked the Guild to relax that requirement and they declined. We have been providing a significant amount of data requested for some time now that does not violate the contract. If she has a complaint, she should take it up with the Guild, which as far as I know, she has not done.”

Regarding the Sheriff’s Office’s labor contracts, Jacobs called on county leaders to negotiate more power for the OLEO into the next contract.

One of Jacobs’ collective bargaining requests? Change the contract so that when OLEO staff go observe the aftermath of a police shooting or similar incident, they’re allowed to actually see the site. Under current contract, Jacobs said, OLEO staff are required to remain at the “command center” when observing an incident, which is typically a car which may or may not be within sight of the actual incident location.

“If we can’t see the processing of a scene,” said Jacobs, “I’m not really sure what we’re doing there.”

cjaywork@seattleweekly.com

Additional reporting has been added to this post.